“The stranger will naturally inquire where lie the heroes of the Alamo, and Texas can reply only by a silent blush.”

Reuben M. Potter, The Fall of the Alamo

On the south side of E. Commerce Street, just east of the San Antonio Chamber of Commerce, you’ll find a fading marble plaque mounted on a low stone wall. On it is written, “On this spot bodies of heroes slain at the Alamo were burned on a funeral pyre. Fragments of the bodies were afterward buried here.” However, this inscription is incorrect. This marble marker isn’t in its original location, so it’s not at the site of one of the Alamo defenders’ funeral pyres or where their ashes were buried.

A newer metal marker, mounted next to it, tells the story of how that time-worn marble plaque came to be in its current location. That marker reads: “The De Zavala Chapter of the Texas Landmark Association placed this marble marker on the M. Halff Building in 1917, which stood near here at the corner of East Commerce and Rusk Streets, to commemorate the location of one of the funeral pyres of the Heroes of the Alamo. When the Halff Building was demolished in 1968 for the extension of the Paseo del Rio (the River Walk), the owners of the building, Mr. and Mrs. William Sinkin, removed the marker and kept it in protective custody. It was reinstalled here in the vicinity of the original location on March 6, 1995, to honor the memory of Adina de Zavala, dedicated patriot, historian, and citizen of Texas, who placed this and over thirty other historic markers throughout the state.”

Sadly, this 1995 marker does little more than acknowledge Adina de Zavala and her many accomplishments and how the marble marker was saved, rather than marking the site of one of the Alamo’s greatest tragedies: where the bodies of the fallen defenders were cremated. And the best they could do was to say “in the vicinity of the original location” as a designation for where those pyres were.

My quest to find the sites of the Alamo defenders’ funeral pyres and what became of their bodies began when I discovered these two markers while researching my Alamo walking tour post, “DISCOVERING THE ALAMO, PART 2: BEYOND THE ALAMO’S WALLS.” However, I soon found this to be a very challenging endeavor.

The area’s massive commercial development and redevelopment had removed streets and buildings, which could have helped locate these historic sites. Legends, myths, and differing witness accounts have clouded what actually became of the bodies of the Alamo’s defenders.

To present my findings accurately, I’ve researched this subject using various Alamo history books, eyewitness accounts, newspaper articles, and archaeological studies.

We begin this multi-part series where the mystery started: on the post-battle morning of March 6, 1836, when the victorious General Antonio López de Santa Anna faced a daunting task.

A Daunting Task

As the sun rose over the smoking Alamo on March 6, 1836, it revealed a sight of unbelievable carnage. The hundreds of dead Alamo defenders and Mexican soldiers killed in that final pre-dawn battle were scattered inside the fort and around its perimeter. Witnesses told how the blood was so deep that it covered their shoes, and the smell of death was overpowering. Lt. Colonel José Enrique de la Peña, an officer in Santa Anna’s army, describes what he saw in his diary, With Santa Anna in Texas. He wrote, “The bodies, with their blacked and bloody faces disfigured by a desperate death, their hair and uniforms burning at once, presented a dreadful and truly hellish sight.”

After the wounded Mexican soldiers had been removed from the battlefield, the victor now had to deal with all the dead. This would be a daunting task considering the sheer number of dead. Between the defenders and the Mexican soldiers, it’s estimated that the number killed to have been between 800 and 1,000.

General Santa Anna had made it clear that he wanted his soldiers honored with a Christian burial. As for the Alamo’s defenders, he saw them as pirates and deserving nothing more than to be burned like the dogs he considered them to be.

However, identifying which of the dead were Santa Anna’s soldiers and those of the Alamo defenders may have been an issue. In a June 30, 1889, article in the San Antonio Express newspaper, Felix Nuñez, a self-claimed sergeant in Santa Anna’s army at the Alamo, told of the condition of the dead. Nuñez stated, “…they couldn’t tell our soldiers from the Americans, from the fact that their uniforms and clothes were so stained with blood and smoke, and their faces so besmeared with gore and blackened, that one could not distinguish the one from the other.” Nuñez went on to say that when this was reported to Santa Anna, he had all the faces of the dead wiped clean to make sure that none of his soldiers would be burned by mistake. Lt. Colonel José Enrique de la Peña gives another account of identifying the dead, “Those of the enemy were distinguished by their whiteness, [and] by their robust and bulky forms.”

Once the bodies had been separated from those of the defenders and Santa Anna’s troops, it was time to dispose of the dead.

The Funeral Pyres of the Alamo Defenders

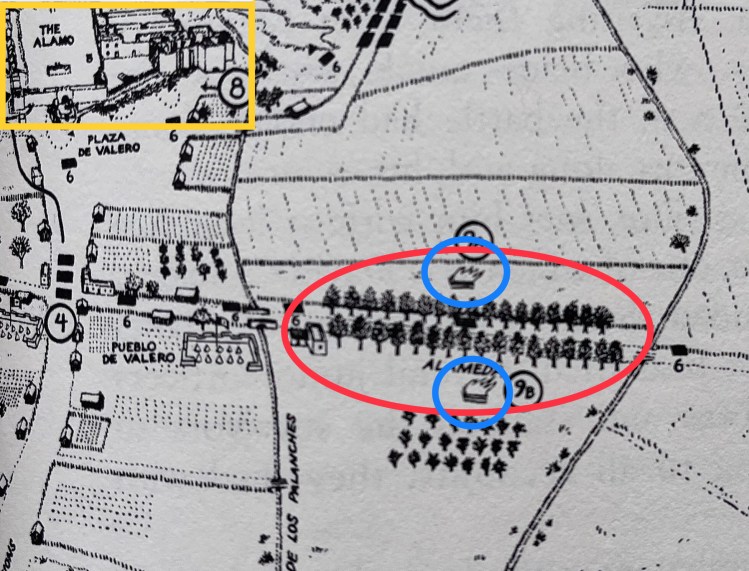

After Santa Anna’s dead and wounded soldiers had been taken out of the Alamo, he turned his attention to the disposal of the defenders’ bodies. In 1889, Sergeant Felix Nuñez described how the defenders’ bodies were then removed. “General Santa Anna immediately ordered every one of the Americans to be dragged out and burnt. The infantry was ordered to tie on the ropes, and the cavalry to do the dragging.” Accounts tell how the Mexican cavalry dragged the defenders’ bodies to a section of road several hundred yards south of the Alamo known as the Alameda.

The Alameda was an avenue located east of the Pueblo de Valero, between two branches of the Acequia Madre or Acequia del Valera irrigation ditches. It was also the western end of the Old Powder House or Gonzalez Road.

What was so striking about this section of road was the flowering cottonwood trees that lined both sides. These trees were believed to have been planted by Spanish soldiers who occupied the Alamo in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. And it was from these trees that the Alameda got its name. Figure #1 helps to visualize the Alameda’s relationship to the Alamo in 1836. This map is by illustrator Gary Zaboly and featured in Alan Huffine’s book The Blood of Noble Men.

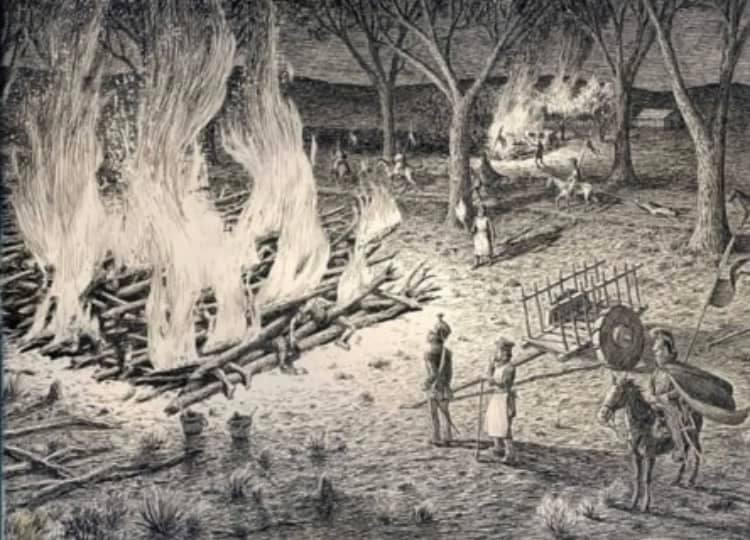

At the Alameda, Santa Anna’s soldiers deposited the bodies at two locations, one on the north side of the road and the other further east on the south side. Once all the bodies had been collected, Francisco Antonio Ruiz, the Alcalde (Mayor) of Bexar, described what happened next. “He [Santa Anna] sent a company of dragoons with me to bring wood and dry branches from the neighboring forest. About 3 o’clock in the afternoon, they commenced laying the wood and dry branches, upon which a file of dead bodies was placed; more wood was piled on them, and another file brought, and in this manner, they were arranged in layers. Kindling wood was distributed through the pile….”

Eyewitnesses told historian and San Antonio Express newspaper reporter Charles M. Barnes that these two pyres were enormous. They stated that the pyre on the north side was between eight to ten feet wide and around sixty feet long. They also told Barnes that it was the smallest of the two pyres. The south pyre, they said, was believed to have been the same width as the north pyre but eighty feet long. These witnesses estimated that both pyres were around ten feet in height.

So, how many defenders were burned on these two pyres? Two witnesses, Nuñez and Ruiz, spoke of this. In Nuñez’s account, he tells how the cavalry counted and dragged the bodies of 180 defenders to the Alameda. While Ruiz said he helped stack 182 bodies onto the pyres. The closeness of these two figures, from two different, unrelated sources, provides a fairly accurate estimate of the likely number of defenders cremated on those pyres. However, one Alamo defender was not burned. Jose Gregorio Esparza’s family was given permission by Santa Anna to bury him in San Fernando Church’s Campo Santo. I’ll tell more about the Campo Santo cemetery in the next section.

Ruiz reported that the two pyres were lit at around 5 o’clock in the afternoon of March 6. The fires grew and intensified almost immediately, surprising the Mexican soldiers and the townsfolk who stood watching. This could have been because it was reported that they added tallow as an accelerant.

Another eyewitness, Pablo Díaz, who was a young man when he witnessed the events of the battle of the Alamo, described what he observed to Charles Barnes in 1906: “I saw an immense pillar of flame shoot up a short distance to the south and east of the Alamo, and the dense smoke from it rose high into the clouds.” Other witnesses told how the pyres burned for two days and nights. These witnesses also stated that the fire was so intense that it killed or damaged some cottonwood trees on Alameda and an orchard of fruit trees near the south pyre.

Witnesses at the pyres tell that after the flames had subsided, all that was left of the brave defenders of the Alamo were a few fragments of bone scattered throughout the still-smoldering ashes. This observation was confirmed by Dr. J.H. Bernard. Dr. Bernard was captured at Goliad and brought to San Antonio to care for Santa Anna’s wounded. After he visited the pyre sites, he described what he saw in his May 25, 1836, journal entry. Dr. Bernard wrote, “The bodies had been reduced to cinders; occasionally a bone of a leg or arm was seen almost entire.” It was reported that Santa Anna had forbidden the burial of the defender’s bones and ashes, leaving them exposed to the elements and wild animals. The only known collection and burial of the defender’s remains didn’t occur until almost a year later, by Juan N. Seguin. I’ll go into more detail on this in another post.

Where the Alameda was is now East Commerce Street, one of the busiest commercial streets in San Antonio. It’s hard to envision that this thoroughfare, now lined with restaurants, office buildings, hotels, and a major shopping mall, once had a section of flowering cottonwood trees and was the site of a horrific cremation. Sadly, no markers today tell where the Alameda would have been in this sprawling urban landscape. In our search, we need to locate where the Alameda was on E. Commerce. Because when we find the Alameda, we will be able to find the locations of the Alamo defenders’ funeral pyres.

Why Did Santa Anna Build the Two Pyres on the Alameda?

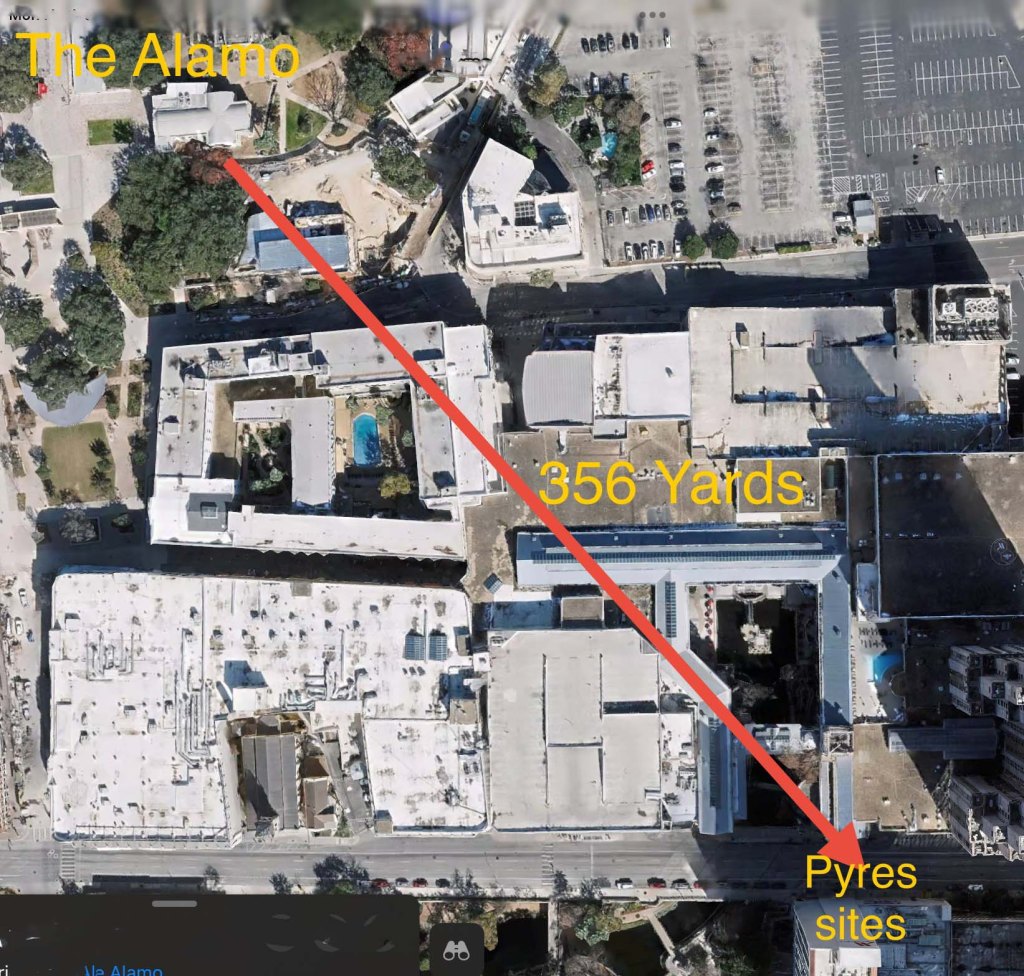

On May 25, 1836, Dr. James H. Barnard wrote in his journal, “We went to visit the ashes of those defenders of our country, a hundred rods [550 yards] from the fort or church to where they burnt.” Twenty-four years later, in 1860, the esteemed Alamo historian Capt. Reuben M. Potter wrote that the location of the funeral pyres was “a few hundred yards from the fort.” Both descriptions indicate that the pyres had been a considerable distance from the Alamo. But were Dr. Barnard and Capt. Potter, referring to the Alameda as being the location of the funeral pyres in their accounts?

To test this theory, I used the Google satellite map measuring tool to calculate, as the crow flies, the distance from the Alamo to the area on E. Commerce Street where I placed the two pyres in PART 3, THE NORTH FUNERAL PYRE, and PART 4, THE SOUTH FUNERAL PYRE. The distance came to approximately 356 yards, which falls closely to Dr. Barnard’s and Capt. Potter’s estimates. So, it’s a logical assumption that they meant the Alameda.

But the question still remains: Why did Santa Anna build the pyres so far away on the Alameda when there were plenty of sites much closer to the Alamo?

To be honest, I didn’t think too much about this until I read Dr. Stephen L. Hardin’s latest book, TEXIAN EXODUS. In Chapter 4: “Confusion and Distress Will Be Indescribable,” Dr. Hardin recounts the post-battle meeting between Susanna Dickinson and Santa Anna, and how Mexican Colonel Juan Almonte convinced Santa Anna to let Mrs. Dickinson carry a message to the rebelling American colonists, warning them that they’d suffer the same fate as those at the Alamo if they continued to rebel against him. As an escort for Mrs. Dickinson, Col. Almonte sent Ben, his African cook. On page 82 of the TEXAS EXODUS, Dr. Hardin tells, “Susanna, Ben, and Angelina rode out of Béxar on the Gonzales Road. But that route forced the party to pass by the smoldering pile of bones and ash that denoted the immolation of Almeron’s [Susanna’s husband] body.” Reading this, it came to me why Santa Anna had built the pyres on the Alameda. And here’s why.

Antonio López de Santa Anna was known to make examples of his enemies. To serve as a warning on what would happen to those who rebelled against him, he used the cremated remains of the Alamo defenders. But for this to be effective, it had to be situated on a well-traveled thoroughfare.

As I wrote earlier, the Alameda was the western terminus of the Gonzales Road, which was the principal trail connecting San Antonio de Béxar with the eastern colonies. So anyone entering or leaving the town would have had to take the Alameda, and thus see Santa Anna’s gruesome reminders. This would also have been why Santa Anna ordered that the ashes of the Alamo defenders not be buried, to keep the reminder whole.

Simply, this is why Santa Anna had his men drag and burn the bodies of Alamo defenders so far from the Alamo on the Alameda.

In PART 2, FINDING THE ALAMEDA, I’ll present a brief history of the development of the Alameda and where the Alameda might have been on today’s E. Commerce Street. Now that we know what became of the bodies of the Alamo defenders, it’s time to discover what became of the other fallen combatants of the Battle of the Alamo.

What Happened to the Bodies of the Mexican Soldiers Killed in the Battle of the Alamo?

Although the focus of this series is to explore the mystery of what became of the remains of the Alamo defenders, we can’t ignore the equally perplexing question: what happened to the bodies of the Mexican soldiers killed in the battle? As I wrote above, Santa Anna had given orders for his fallen soldiers to have a proper Christian burial. But were his orders followed, and to what extent?

What became of the bodies of the Mexican soldiers killed in the battle of the Alamo is as mysterious as that of the Alamo defenders. In this section, I’ll present two possible scenarios of what may have become of the Mexican dead, and one is somewhat gruesome.

I’ve based these possible scenarios on the various reported accounts that explicitly deal with the Mexican dead. I’ll begin with Alcalde Francisco Antonio Ruiz’s account.

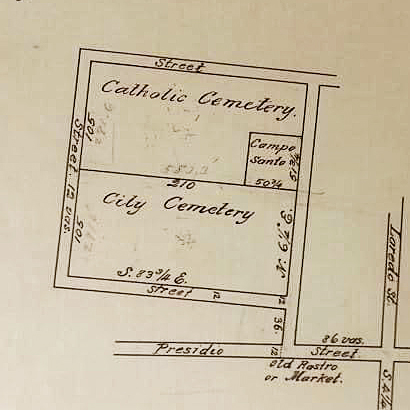

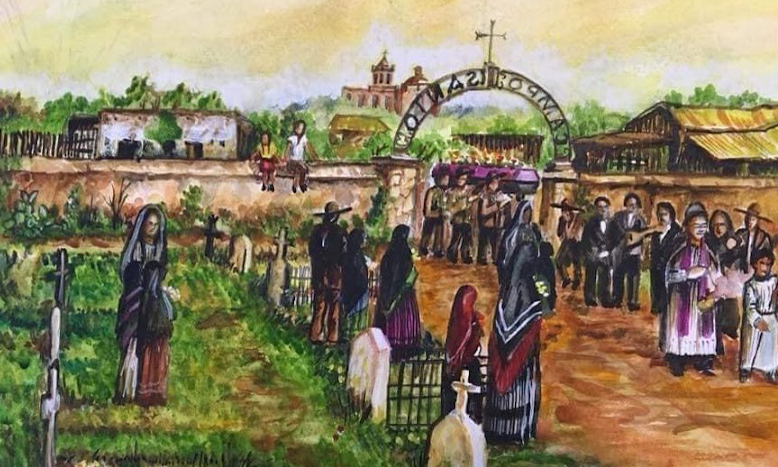

In an 1860 interview, Ruiz tells how he and other townspeople were forced by Santa Anna to cart the bodies of the dead soldiers from the Alamo to San Fernando Church’s Campo Santa cemetery. Figure #2 shows where the old Campo Santo would have been in relation to the San Fernando Cathedral and the Alamo.

Mexican Soldiers’ Bodies Thrown in the River

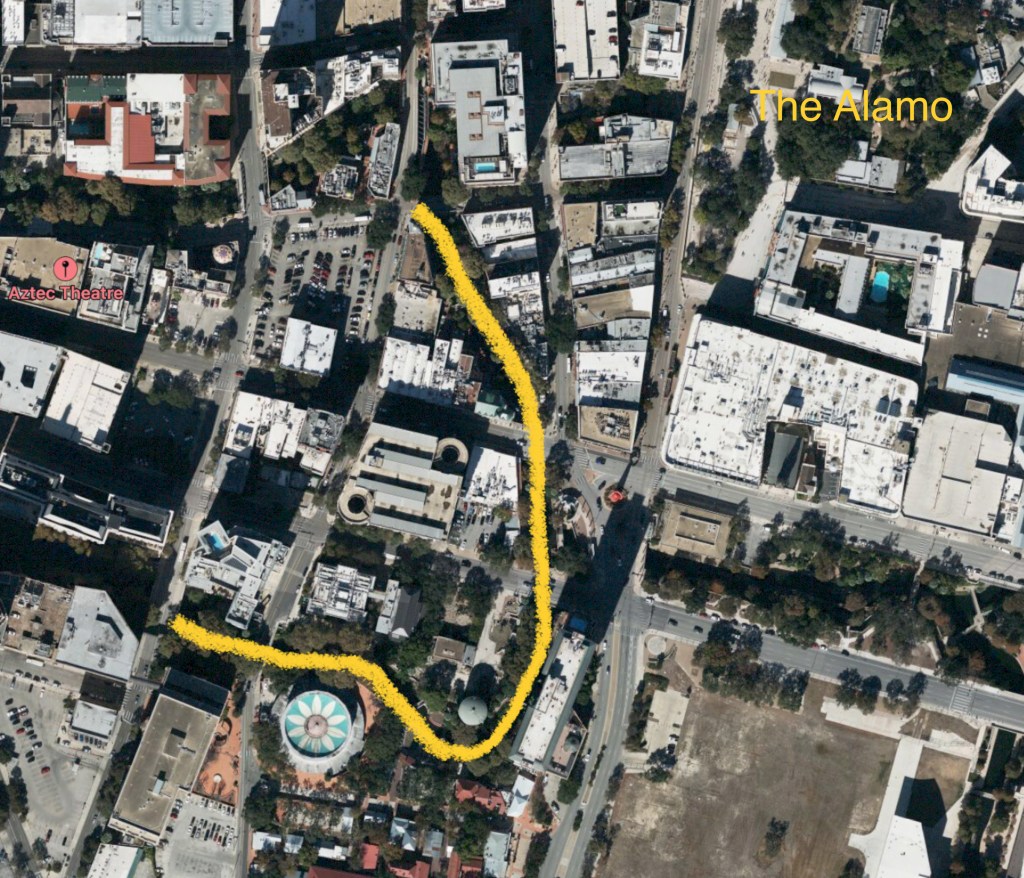

Founded in 1808 on the northwest outskirts of town, across Pedro Creek, San Fernando Church’s Campo Santo (Holy Ground) occupied around eighteen acres. Records tell that by 1836, this walled cemetery was nearing its burial capacity and would have been unable to handle the large numbers of Mexican soldiers killed. In his 1860 interview, Ruiz discussed this issue and the decision he was compelled to make. Ruiz said, “The Mexicans of Santa Anna’s army were taken to the graveyard, but not having sufficient room for them, I ordered some of them to be thrown in the river.”

For me, this account by Ruiz seems too gruesome and outlandish. Who, especially the mayor, would dump corpses into the river that flowed through their town? However, Ruiz’s account is supported by Pablo Díaz.

The 90-year-old Pablo Díaz described to Charles Barnes what he saw: “I noticed that the air was tainted with the terrible odor from many corpses, and I saw thousands of vultures flying above me. As I reached the ford of the river my gaze encountered a terrible sight. The stream was congested with the corpses that had been thrown into it. The Alcade [sic], Ruiz, had vainly endeavored to bury the bodies of the soldiers of Santa Anna who had been slain by the defenders of the Alamo. He had exhausted all of his resources and still was unable to cope with the task. There were just too many of them.”

In a 1911 follow-up article by Barnes, Díaz goes into greater detail on Ruiz’s actions. Díaz told Barnes that when Ruiz was faced with limited grave space, he only buried the Mexican officers in Campo Santo. After which, Ruiz cast the remaining bodies, those of the regular soldiers, into the river. In this later account, Díaz also recounts how Santa Anna became “nauseated” by the stench of the dead and reprimanded Ruiz for his actions. Díaz ends by saying that Ruiz finally dislodged the bodies, which floated downstream to be devoured by the vultures and wolves.

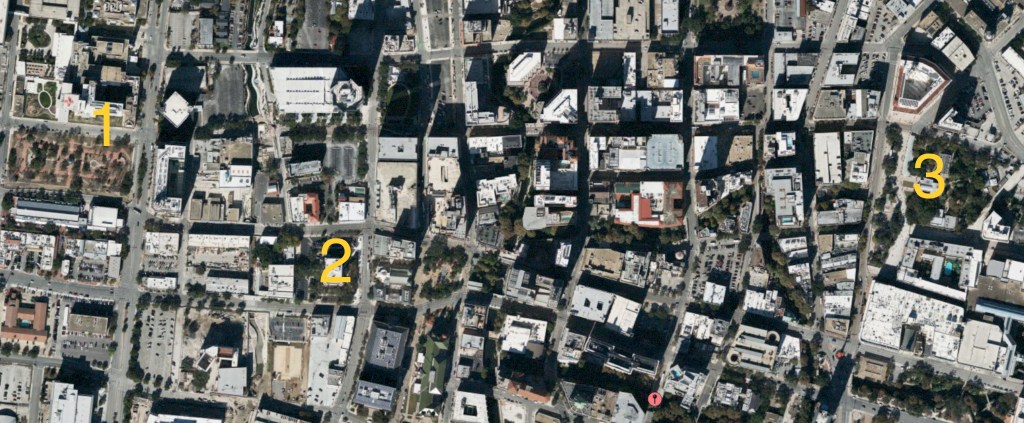

To visualize the scope of this atrocity, we need to go to the Riverwalk in downtown San Antonio. According to Díaz, the bodies in the river stretched from “the ford at the old Lewis Mill,” this would be where the Navarro Street bridge is today, upriver past La Villita, and pass E Commerce Street, all the way up to the Crockett Street pedestrian bridge. According to Díaz, this entire section of the river was choked with the bodies of the Mexican soldiers.’ I’ve highlighted this area in Figure #3.

There’s another possible scenario to consider on what may have become of the bodies of the Mexican soldiers, and this comes from Mexican soldiers themselves.

One of the first recorded accounts is from Lt. Colonel José Enrique de la Peña. In his diary, de la Peña wrote, “The greater part of our dead were buried by their comrades.” This is supported by another Mexican soldier, Sergeant Francisco Becerra, who said in an 1882 interview, “During the evening we buried our dead. These were sad duties which each company performed for its fallen members.” And although he wasn’t a soldier, we also have Enrique Esparza’s account.

Esparza was eight years old at the time of the battle and survived the final attack by hiding with his family in the sacristy of the Alamo Church. Esparza said in a 1902 interview that he witnessed the Mexican soldiers burying their dead over three days.

While these accounts clearly tell that the Mexicans buried their fallen, they neglect to say where these burials took place. However, Manual Loranca, another soldier under Santa Anna, does provide a site. Lorance tells how he helped to bury over 400 of his fellow soldiers in San Fernando’s Campo Santo.

But how could this be? If Ruiz couldn’t bury the Mexican dead in Campo Santo due to the lack of space, then how could Loranca and the others have buried them there? Could there be another answer? Yes, there is.

Mexican Soldiers Buried in San Antonio’s Old City Cemetery

As I stated, records show that by 1836, the Campo Santo cemetery was nearly full. However, the land around the cemetery was still vacant and open. Because the Catholic cemetery was already there, the townsfolk had begun burying their non-Catholics and unbaptized on the land next to and south of Campo Santo. Could it have been on this land, and not Campo Santo itself, that Lorance was referring to? This possibility is supported by Alamo survivor Susanna Dickinson.

In 1875, Dickinson told how the Mexicans had buried their soldiers killed in the battle in the old City Cemetery. This would have been a correct reference point for Dickinson, as the land next to Campo Santo, which was already being used as an unofficial cemetery, became San Antonio’s first city cemetery in 1848. Later accounts tell that the Mexican soldiers were buried in Milam Park. This is also correct because Milam Park was the old City Cemetery. So, the unofficial cemetery of 1836 became the City Cemetery in 1848 and is now known as Milam Park, all on the same piece of land. Could this be where the Mexican soldiers had buried their fallen? Figure #4 Is an 1848 City Survey showing the locations of the Old Campo Santo and the Old City Cemetery. I go into greater detail on the history of these two old cemeteries in DISCOVERING THE ALAMO, PART 3: THE LOST CEMETERIES OF SAN ANTONIO.

So, which of these scenarios is the most plausible? The throwing of the bodies of the Mexican soldiers into the San Antonio River appears only in the accounts of Francisco Ruiz and Pablo Díaz. Still, it isn’t mentioned in other reliable sources. The burying of the fallen soldiers is told by at least three of Santa Anna’s men and is also supported by Enrique Esparza. In addition, Susanna Dickinson and others say that the Mexican soldiers buried their dead in what is now Milam Park.

We have one other piece of evidence to consider. According to the burial records of the San Fernando church, at least two of Santa Anna’s soldiers were buried in the old Campo Santo. Their cause of death is listed as “from wounds in the battle of the Alamo.” Could these have been officers buried by Ruiz? Or of those buried by their fellow soldiers? Until more evidence surfaces, it’s still speculation.

I should mention a couple of other less trustworthy accounts. One comes from William Cannon. In 1893, Cannon claimed to have been a defender who had avoided the slaughter of the final battle by hiding. Cannon told how he had seen the Mexicans burying their dead in the Plaza de Valero, between the Alamo’s south wall and where the Menger Hotel is today. Others say that the Mexicans buried some of their dead in the Alamo’s defensive trenches or even tossed some of the Mexican bodies onto the burning funeral pyres with those of the defenders. As I said, these are less than trustworthy.

Coming soon: Part 2, FINDING THE ALAMEDA

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

“Alamo Funeral Pyre.” HMdb.org, Historical Markers, 19 Aug. 2019, http://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=30589.

“Alamo Funeral Pyre.” Texas Historical Markers, Texas Historical Markers, texashistoricalmarkers.weebly.com/funeral-pyre.html. July 2022.

Allen, Paula. “City cemetery records kept at Central Library .” MYSA, My San Antonio, 5 Dec. 2011, http://www.mysanantonio.com/article/City-cemetery-records-kept-at-Central-Library-2338581-php.

City of San Antonio. “Alamo Cenotaph.” Mission Trails, City of San Antonio , http://www.sanantonio.gov/Mission-Trails-Historic-Sites/Detail-Page/ArtMID/16185/ArticleID/4419?Alamo-Cenotaph. Nov. 2022.

de la Peña, José Enrique. “Chapter 4.” With Santa Anna in Texas, translated by Carmen Perry, EXPANDED EDITION, Texas A & M University Press, 1975, p. 52.

de la Peña, José Enrique. “Chapter 4.” With Santa Anna in Texas, translated by Carmen Perry, EXPANDED EDITION, Texas A & M University Press, 1975, p. 55.

Fox, Anne A., and Marcie Renner, editors. “The Ludlow House and Moody Site.” Historical and Archaeological Investigations at the Site of Rivercenter Mall (Las Tiendas) San Antonio, Texas, edited by I. Waynne Cox et al., principal investigator by Robert J. Hard et al., Center for Archaeological Research The University of Texas at San Antonio, 1999, p. 80. Center for Archeological Research, Archeological Survey Report No. 270 , car.utsa.edu/CARResearch/Publications/ASRFiles/201-300/ASR%20No.%20270.pdf.

Hansen, Todd. “Builders’ Spades Turn Up Soil Baked by Alamo Funeral.” The Alamo Reader, A Study in History, First Edition, STACKPOLE BOOKS, 2003, p. 539. From historian and reporter Charles Merritt Barnes’s article, “Builders’ Spades Turn Up Soil Baked by Alamo Funeral Pyres,” which appeared in the San Antonio Express newspaper on March 26, 1911.

Hansen, Todd. The Alamo Reader, A Study in History, First Edition, STACKPOLE BOOKS, 2003.

Hansen, Todd. “Francisco Antonio Ruiz 1860 account.” The Alamo Reader, A Study in History Frist Edition, STACKPOLE BOOKS, 2003, p. 501.

Hansen, Todd. “Pablo Díaz 1906 interview. The Alamo Reader, A Study In History, First Edition, STACKPOLE BOOKS, 2003, p. 530.

Hansen, Todd. “Francisco Antonio Ruiz 1860 account.” The Alamo Reader, A Study in History Frist Edition, STACKPOLE BOOKS, 2003, p. 501.

Hansen, Todd. “Builders’ Spades Turn Up Soil Baked by Alamo Funeral.” The Alamo Reader, A Study in History, First Edition, STACKPOLE BOOKS, 2003, p. 539.

Hansen, Todd. “Felix Nuñez Interview of 1889.” The Alamo Reader, A Study in History, First Edition, STACKPOLE BOOKS, 2003, p. 483.

Hansen, Todd. “Francisco Antonio Ruiz 1860 account.” The Alamo Reader, A Study in History Frist Edition, STACKPOLE BOOKS, 2003, p. 501.

Hansen, Todd. “Third Eye-Witness” “Builders’ Spades Turn Up Soil Baked by Alamo Funeral.” The Alamo Reader, A Study in History, First Edition, STACKPOLE BOOKS, 2003, p. 540.

Hansen, Todd. “Builders’ Spades Turn Up Soil Baked by Alamo Funeral.” The Alamo Reader, A Study in History, First Edition, STACKPOLE BOOKS, 2003, p. 539.

Hansen, Todd. “Felix Nuñez Interview of 1889.” The Alamo Reader, A Study in History, First Edition, STACKPOLE BOOKS, 2003, p. 483.

Hansen, Todd. “Dr. Bernard, journal, 1836 and later? The Alamo Reader, A Study In History, First Edition, STACKPOLE BOOKS, 2003, p. 615.

Hansen, Todd. “Felix Nuñez Interview of 1889.” The Alamo Reader, A Study in History, First Edition, STACKPOLE BOOKS, 2003, p. 483.

Hardin, Dr. Stephen L. ““Confusion and Distress Will Be Indescribable,”.” Texian Exodus, first Edition, University of Texas Press, 2024, p. 82.

“Hemisfair .” Office of Historic Preservation, City of San Antonio, http://www.sanantonio.gov/historic/scoutsa/HistoricDistricts/HemisFair. Sept. 2022.

Huffines, Alan C. . The Aftermath.” Blood of Noble Men. The Alamo, Siege & Battle, illustrated by Gary S. Zaboly, first Addition, Eakin Press, 1999, p. 190.

“Independent Order of Odd Fellows San Antonio Lodge 11 Cemetery.” Historic Houston: Old San Antonio City Cemeteries, Archival Press, historichouston1836.com/san-antonio-historic-cemeteries/#:text=Grand%20United%20Order%20Order%20of%20Odd,%20particularly%20striking%20grave%20markers. May 2022.

Jackson Jr., Ron J. “Skeletons in Buckskin at the Alamo.” HistroyNet, Wide West, 15 Jan. 2021, http://www.historynet.com/skeletons-in-buckskin-at-the-alamo/?f.

jrboddie. “The Alameda .” Alamo Studies Forum, Alamo Studies Forum, 17 Apr. 2014, alamostudies.proboards.com/thread/1674/alameda.

“M. Halff & Bro. Building, southwest corner of E. Commerce and Rusk Streets, San Antonio Texas, ca 1941.” UTSA Libraries Special Collections Digital Collections, University of Texas San Antonio , digital.utsa.edu/digital/collection/p9020coll7/id/76. Apr. 2022.

Matovina, Timothy M. “The Story of Don Pablo.” The Alamo Remembered, Tejano Accounts and Perspective, University of Texas Press, Austin, 1995, p. 104.

Matovina, Timothy M. “The Burning of the Bodies’ The Alamo Remembered, Tejano Accounts and Perspective, University of Texas Press, Austin, 1995, p. 105.

Matovina, Timothy M. “Fall of the Alamo, The Massacre of Travis and His Brave Associates, Francisco Ruiz 1860 account” The Alamo Remembered, Tejano Accounts and Perspective, University of Texas Press, Austin, 1995, p 44.

Matovina, Timothy M. “Aged Citizen Describes Alamo Fight and Fire: Díaz Saw Terrible Carenag”e The Alamo Remembered, Tejano Accounts and Perspective, University of Texas Press, Austin, 1995, p. 75.

Matovina, Timothy M. “Builders’ Spades Turn Up Soil Baked by Alamo Funeral Pyres” “Third Eyewitness” The Alamo Remembered, Tejano Accounts and Perspective, University of Texas Press, Austin, 1995, p. 105.

Matovina, Timothy M. “The Story of Don Pablo.” The Alamo Remembered, Tejano Accounts and Perspective, University of Texas Press, Austin, 1995, p. 104.

Matovina, Timothy M. “Aged Citizen Describes Alamo Fight and Fire,” “He Saw the Ashes of the Heroes” The Alamo Remembered, Tejano Accounts and Perspective, University of Texas Press, Austin, 1995, p. 76.

Matovina, Timothy M. “Aged Citizen Describes Alamo Fight and Fire,” “He Saw the Ashes of the Heroes” The Alamo Remembered, Tejano Accounts and Perspective, University of Texas Press, Austin, 1995, p. 76-77.

McKenzie, Clinton M.M, et al. “An Archival and Archaeological Review of Reported Human Remains at the Alamo Plaza and Mission San Antonio de Valero San Antonio, Bexar County, Texas.” Jason Perez and Sarah Wigley, special Report No. 36, Center for Archaeological Research The University of Texas San Antonio, 2022.

Nelson, George. “Map of the Alamo 1836.” The Alamo, An Illustrated History, third Revised , Aldine Press, 2009, p. 5.

“Post Office Burials Unearthed in 1935.” Alamo Studies Forum, Alamo Studies Forum, 21 Dec. 2007, alamostudies.proboard.com/thread/301/post-office-burials-unearthed-1935.

Potter, Reuben M. The Fall of the Alamo. Introduction and notes by Charles Grosvenor, The Otterden Press, 1977, pp. 46-47.

Reveley, Sarah. “Hallowed Ground: Site of Alamo Funeral Pyres Largely Lost to History .” San Antonio Report, San Antonio Report, 7 Jan. 2017, sanantonioreport.org/hallowed-ground-site-of-alamo-funeral-pyres=largely-lost-to-history/.

Roberts, Randy, and James S. Olson. “Retrieving the Bones of History.” A Line In The Sand, The Free Press, 2001, p. 199.

Romero, Simon. “Burial Ground Under the Alamo Stirs a Texas Feud.” The New York Times , The New York Times , 25 Nov. 2021, www.nytimes.com/2021/11/25/us/alamo-burial-native-americans.html.

Ruiz, Francisco Antonio. “The Story of the Fall of the Alamo.” Sons of the Dewitt Colony, Sons of the Dewitt Colony, www,sonsofthedewittcolony.org/adp/archives/newsarch/ruizart.html. Feb. 2022. As it appeared in the San Antonio Light newspaper of Sunday March 6, 1907.

San Antonio Parks & Recreation. “Historic City Cemeteries & Burial Parks.” Explore The Fun!, San Antonio Parks & Recreation , http://www.sanatonio.gov/ParksAndRec/Parks-Facilities/All-Parks-Facilities/Historic-City-Cemeteries. Accessed 11 Jan. 2023.

“San Antonio River Walk.” Wikipedia, Wikipedia, June 2022, en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/San_Antonio_River_Walk.

Sons of Dewitt Colony Texas. “The Disposition of the Alamo Defenders’ Ashes.” The Sons of Dewitt Colony Texas , The Second Flying Company of Alamo De Parra, http://www.sonsofdewittcolony.org/adp/central/forum/forum9.html. Jan. 2023.

Troesser, John. “The Spirit of Sacrifice, aka The Alamo Cenotaph.” Texas Escapes , Texas Escapes, www.texasescapes.com/SanAntonoTx/The-Alamo-Cenotaph.htm. Oct. 2023.

Waymarking. “Capt. R.A. Gillespie & Capt. S.H. Walker Obelisk-Odd Fellows Cemetery-San Antonio, Tx.” Waymarking, Waymarking , www,waymarking.com/waymarks/WMTBR4_Capt_RA_Gillespie_Capt_S_H_Walker_Obelisk_Odd_Fellows_Cemetery_San_Antonio_Tx. Jan. 2023.

“Where are the Ashes of the Alamo Defenders.” Usbekistan, usbekistan.at/pjjgt/where-are-the-ashes-of-the-alamo-defneders-. Jan. 2023.

Wikipeda. “Samuel Hamilton Walker .” Wikipedia , Wikipedia , 13 Dec. 2023, http://www.wikipedia.org/wki/Samuel_Hamilton_Walker .

Wikipedia . “Old San Antonio City Cemeteries Historic District.” Wikipedia, Wikipedia, Oct. 2022, en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Old_San_Antonio_City_Cemeteries_Historic_District.

Zaboly, Gary S. “The Funeral Pyres.” State House Press, 2011, p. 273.

Ive read all your stories here and they are very interesting ! Something Ive always just wondered is “the spoils of war” ? What happened to many of the arms and other accessories required ? There were known a few “rifles” brought and used and I guess many were damaged / destroyed during the battle but all ? Other personal items would of been discovered by the Mexican troops as they “processed” the remains ? If these items went into the fires among the bodies there would be remnants buried in the ground below ? Is this something you have explored or plan to ?

Paul

LikeLike

To the victors… Thanks for the question, Paul

According to Mexican Soldier Felix Nunes, “After we had finished our task of burning the Americans, a few of us went back to the Alamo to see what we could pick up valuable.” Other accounts tell how the Mexicans stripped the defenders’ bodies before burning them.

As for records of what the Mexicans acquired, there are none. I know that one of the rifles on display at the Battle For Texas: The Experience came from a Mexican family who got it from an ancestor who fought with Santa Anna. Other items retrieved could be in the Alamo Museum or in the Phil Collins collection could also be retrieved. We know that after the Battle of San Jacinto, those Mexicans stationed at the Alamo buried the fort’s cannons. The New Orleans Gray flag, which flew over the Alamo, is on display in a museum in Mexico City.

As for writing a post on this subject , I’m not sure. But it’s something to think about.

Ron

LikeLike

wow!! 79SEARCHING FOR THE REMAINS OF THE ALAMO DEFENDERS: PART 4, THE SOUTH PYRE

LikeLike