Where was the Alamo’s 18-Pounder cannon located? Where was Travis’s headquarters where he wrote his famous “Victory or Death” letter, and where did Davy Crockett and Jim Bowie die? These and other questions about the Alamo are constantly asked by those visiting this historic place. But trying to find those spots can be a challenge. The reason, a major portion of the Alamo’s original battlefield has been covered over by the growth of the City of San Antonio. So, does this mean that discovering those locations is impossible? No. Many of the sites are well marked and hidden in plain sight, you just need to know where to look. And that’s the reason I wrote this post, to help you navigate around today’s city streets to find “the Alamo.”

In this post I’ll take you around the Alamo fort’s original grounds, showing the sites from the 1836 Battle of the Alamo, as well as other points of interest. To write this post I used my research from my other posts on the history of the Alamo, and what I learned during my pilgrimages to the Alamo in 1986, 2011, and 2018. During those trips, I sought out the locations of events from that battle, with some locations being far from the Alamo Plaza itself. However, three sources were extremely helpful in writing this walking tour: Dean Kirkpatrick’s The Alamo Story and Battleground Tour, Mark Lemon’s The Illustrated Alamo 1836, A Photographic Journey, and the tour I took of Alamo Plaza in 2018, hosted by the Sons of the Republic of Texas (SRT).

As I stated above, my last visit to the Alamo was in 2018, and this walking tour post was first published in 2019. Since then, the Texas General Land Office (GLO) and the Alamo Trust, Inc. (ATI), who now operate the Alamo, have been doing an outstanding job in bringing the Alamo to life. In 2021, the GLO and ATI installed two exhibits on the Alamo’s grounds, the 18-Pounder/Losoya House and the Palisade, which I tell about in this post. So, with each new addition to the site, I can safely say that this walking tour will indeed continue to be updated.

In addition, the Alamo also offers their own tours, but since I’ve not taken one of these, I’m not sure what they cover. Saying that, if you’re unable to visit the Alamo yourself, or if you want to tour on your own, this post will help you.

So, without further ado, let’s discover the hidden Alamo!

This post was updated on March 11, 2022

Finding the Alamo

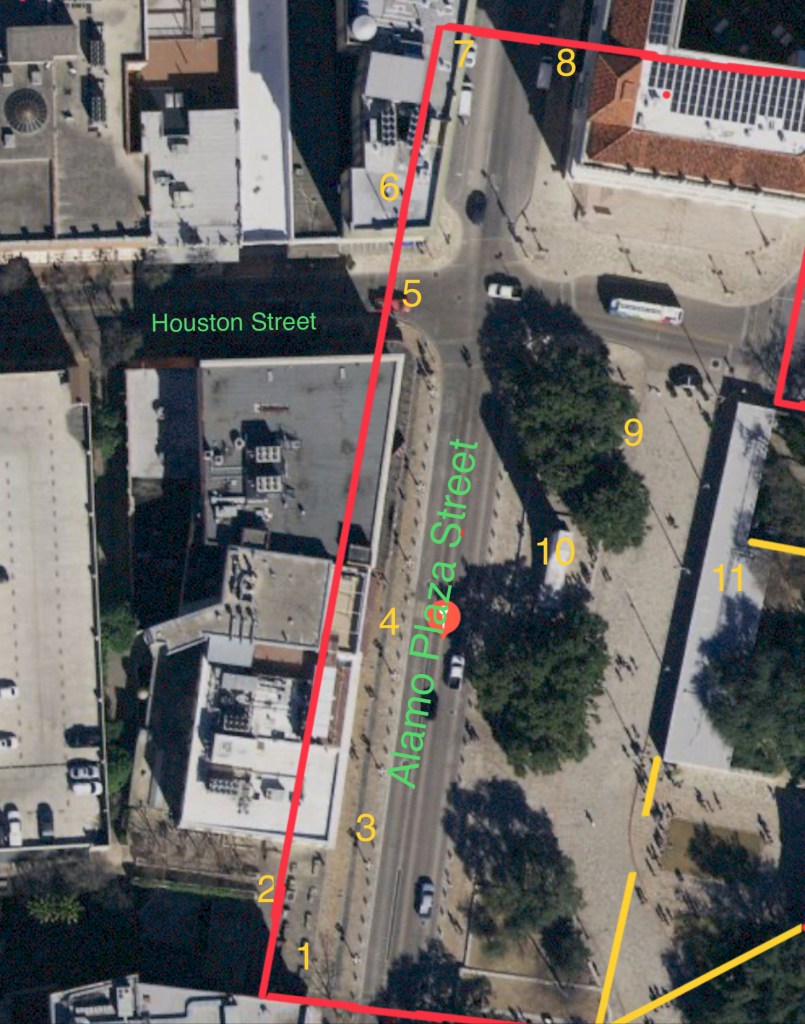

Finding the Alamo can be a challenge for the casual visitor. In fact, when you’re on Alamo Plaza gazing at “The Alamo,” you’re already standing deep inside what was this historic fort. What most call the Alamo is only its church. The original Alamo complex of walls and buildings covered nearly 3 acres, with only about 10% currently preserved. Since most of the Alamo has been engulfed by the growth of San Antonio over almost two centuries, I needed a visual aid to help identify where to find the different battle sites of the Alamo.

To try and accomplish this in my 2014 tour post I used a photo I had taken from the top of the Tower of the Americas, and though it did show how the City of San Antonio had closed in on the Alamo, it wasn’t very helpful in identifying where the different battle sites were around Alamo Plaza.

For this post, I used a Google satellite photo of the Alamo’s area and created an overlay of the original Alamo compound on it. With this resource, we can now locate important sites, which mostly go unnoticed.

I’ve also enlarged different sections of my map and numbered the different spots that I’ll be writing about, so you’ll be able to find them when you visit the Alamo.

Sites on the West Side of the Alamo Compound

We’ll begin our exploration at a small open area (See map #1) on the west side of Alamo Plaza Street, across from the Alamo church. It’s not hard to find this spot, because of the many odd-shaped light brown brick walls that have been placed there.

This is the spot where the Alamo’s south and west walls met. And this is where the fort’s largest cannon, the 18-pounder, was placed. On February 23rd, 1836, the first day of the siege, Alamo Commander Colonel William Travis, used this cannon to answer Santa Anna’s demands to surrender.

The odd stone walls represent the original walls and building foundations that archaeologists had discovered. Be sure to check out the glassed-in display, where you can see one of those foundations.

The Alamo’s West Wall

A new piece of information I learned during my Sons of the Republic of Texas (SRT) tour was about the higher wall at the back of this site (See map #2). This wall runs parallel to Alamo Plaza Street and ends at the Losoya walkway. What this wall indicates is where the Alamo’s outer wall stood. During the battle, this wall was about 9 to 12 feet high, and 2 to 3 feet thick. But what really struck me was how far back from the street the wall actually was, and also how far inside the buildings it ran.

We’re now going to leave the forts southern corner and head north toward Houston Street, along what was the Alamo’s west wall. As you walk along I just want you to realize, that even though you’re surrounded by the hustle and bustle, and the noise of the city, you’re walking on one of the most historic battlefields in the world.

As you’re walking notice the wide line of darker material running north and south embedded in the sidewalk. This line indicates the location of a dry ditch (See map #3) that ran outside the houses on the west wall.

These street markings are another new discovery, thanks again to the guides of the SRT. Recognizing and knowing what these markers represent is extremely helpful in understanding the original Alamo site. I’ll be pointing out more of these as we go along.

On the left is a series of three buildings that now occupy this section of the fort’s west wall: the Crockett, built-in 1862, the Palace Theater, built-in 1923, and the Woolworth, built-in 1921. These buildings currently house the most controversial businesses on Alamo ground: Ripley’s Haunted Adventure, Guinness World Records, and 3D Tomb Raider. In 2015, the Texas General Land Office (GLO) purchased these three buildings for $14.4 million, with the plans to convert them into a 100,000 square foot Alamo museum.

Travis’s Headquarters

When you reach the entrance to Ripley’s Haunted Adventure, you are now at the general location where one of the Alamo’s most famous houses stood, the Trevino House (See map #4). The name may not mean anything to you, but it was the headquarters of William Travis, and where he wrote his famous February 24, 1836 letter for help, “To the people of Texas and all Americans in the world.”

The Castaneda House

When you reach the end of the block, look down at the pavement on Houston Street (See map #5). Once again you’ll see darker pavers. Until I took the SRT tour I thought these were pedestrian crosswalk markings, however, I was wrong. What these markings really indicate is the foundations of what was most likely the Castaneda House. During the battle, this house was already in ruin and believed that it held a 6-pounder cannon placement.

The Hotel Gibbs

We’re going to continue north, crossing Houston Street. On the northwest corner is the small boutique Hotel Gibbs (See map #6). Hotel Gibbs now occupies what was originally the Gibbs Building. The Gibbs Building was constructed in 1909 by Colonel C C Gibbs. With its eight floors, the Gibbs Building was the first high-rise in San Antonio.

There’s also another piece of Alamo history that happened at this spot. Col. Gibbs had built his office building on what was the site of the home of one of San Antonio’s most famous developers, Samuel Maverick. It was while Maverick was excavating for his house in 1852, that he discovered a trove of Alamo cannons that had been buried there by the Mexican Army after the Battle of San Jacinto. These cannons have been recently restored and are on display at the Alamo. I’ll tell more about this later in this post.

The North Wall

As we continue north toward the back of the hotel, I want you to keep your eye on the sidewalk. Near the back of the building, you see a small marker on the sidewalk (See map #7). While not as large as the others we’ve seen so far, it may be one of the most important in understanding how really big the Alamo fort really was.

This small metal marker has an angled line: one end pointing south, and the other to the east. It reads ALAMO MISSION ORIGINAL PROPERTY CORNER. This indicates where the Alamo’s west and north walls had met. However, this marker isn’t completely accurate; remember the west wall’s true location is still several feet west, inside the hotel. But it does show how far back from Alamo Plaza the north wall really was. But there’s another marker that does show the true location of the Alamo’s north wall. To find this we’ll need to cross to the other side of N Alamo Street.

On the east side of the street is the massive Hipolito F. Garcia Federal Building and U.S. Courthouse. Built in the mid-1930s, as part of the WPA program, it has a polygonal design and is constructed of Texas Pink granite and Texas Cream limestone. Not only does the Garcia building encompass an entire city block, but it also occupies a good portion of where the Alamo’s north wall was.

Again, on the sidewalk, just a few steps back from the building’s side entrance is another small metal marker (See map #8). This one has a line pointing east and west that reads, ALAMO MISSION ORIGINAL PROPERTY LINE. A very underwhelming description of what actually happened there.

It was here, during Santa Anna’s pre-dawn attack on Sunday, March 6, 1836, that the masses of Mexican soldiers finally overcame the defenders, rolling over the north wall, and gaining the inside of the fort. It was also here where William Travis gave his life. And that’s how important the north wall is to Alamo history.

If you look back toward Alamo Plaza, you’ll see how far removed this famous and historical spot is from what is known as “the Alamo”

Now that we’ve been to the furthest northern location of the original Alamo’s grounds, it’s time to head back to Alamo Plaza and the Long Barrack building.

Alamo Plaza

Today Alamo Plaza (See map #9) is a large and active city park, but it was much, much, larger during the battle. Taking into account all the way back from where we came at the north wall, and adding the portions inside the buildings along Alamo Plaza Street, the original measurements of the compound would have been around 462 feet long by 162 feet wide.

The modern Alamo Plaza was created by Samuel A. Maverick. Maverick bought up most of the Alamo’s land and then subdivided it for his commercial and residential developments. Maverick created the plaza to be a gathering place for city residents and deeded it to the City of San Antonio. This plaza has seen it all: chili cook-offs, longhorn cattle, street preachers, political rallies, and loud protesters.

This usage of Alamo Plaza has been a hot topic of criticism by those who see this area as hallowed ground. And why passions run high, and rightly so, is because of what happened there in the pre-dawn of March 6th, 1836.

That morning, Mexican soldiers having breached the north wall, advanced across this space, causing the defenders to fall back into the Alamo’s Long Barrack and the houses along the west wall. It was on this open area where many men, both defenders, and attackers, lost their lives.

While it’s still owned by the City of San Antonio, the plaza is now part of a 50-year operational agreement with the State of Texas’s General Land Office (GLO). GLO now manages the Alamo’s two original buildings, as well as the newly purchased buildings on the old west wall. Under this agreement, the GLO will be responsible for the total management and also a reclamation of the Alamo’s historic battlefield. But this agreement has come under criticism.

There is one historic outcome from this agreement; this is the first time since the Catholic Church-owned these grounds, that one entity has control over what was the original Alamo compound.

The Alamo Cenotaph

Near the center of Alamo Plaza stands the inspiring, 60 foot tall gray Texas granite, Spirit of Sacrifice monument (See map #10). Most commonly known as the Alamo Cenotaph (meaning empty tomb) it was constructed in honor of the 100th anniversary of the Battle of the Alamo in 1936. Dedicated on November 11, 1940, the Cenotaph features carvings of fallen Alamo defenders: William Travis, James Bowie, David Crockett, and James Bonham. It also has a listing of those defenders that were killed during that battle.

There’s a popular myth that says the cenotaph sits on the site of one of the funeral pyres of the Alamo defenders. However, this is most likely not accurate. I’ll go into more detail on this subject with my future post, “Where are the Remains of the Alamo’s Heroes?”

The Long Barrack

The 192-foot long, yellowish-brown, single-story stone building bordering the east side of Alamo Plaza is the Alamo’s Long Barrack (See map #11). The Long Barrack is one of the two remaining Alamo mission/fort buildings, the other being the church. The Long Barrack is also considered to be the older of the two; however, this also isn’t truly accurate.

In my History of the Alamo post series I tell of the Long Barrack’s disastrous, or should I say destructive, history. From the U.S. Army, and through the varied store owners, the Long Barrack’s stone walls had been cut, removed, or filled in. What I’ve learned is that only its outer west wall is somewhat original. The rest of the building is a reconstruction, using some of its original stones, but still a reconstruction. Even this west wall, that you see today, isn’t as it was during the battle. However, it’s not what remains of this building that’s important, it’s to remember what happened inside its walls.

During the final battle, the Alamo’s defenders used the Long Barrack as their second line of defense. From its doorways and holes dug into its walls, the defenders were able to train their rifles on the Mexican soldiers pouring into the plaza. It wasn’t until the Mexicans turned the Alamo’s own cannons on the doorways that the tide of the battle turned to the attackers. With the doorways now cleared, Santa Anna’s troops rushed in; and there, in the dark and smoke-filled rooms, some of the fiercest and bloodiest fighting took place.

So when you’re standing in front of the Long Barrack or visiting the museum inside, remember those, both defenders and attackers, who paid so dearly there for what they believed in.

Also, as you walk along next to the Long Barracks on Alamo Plaza, you’ll notice seven bronze models of the Alamo compound. Designed by George Nelson, and donated by musician Phil Collins, they depict what the Alamo looked like from 1744 to the time of the 1836 battle.

Sites on the East Side of the Alamo Compound

The Mission’s Convento Courtyard

Around the south end of the Long Barrack, you’ll see the Alamo church. But we’re not going to stop there now, we’ll come back to it later. Right now we’ll go through the gate to the left, and into the Mission’s Convento Courtyard (See map #12).

During the mission period, the mission Indians would have worked in the rooms that surrounded this courtyard. They would have been doing such tasks as spinning yarn, candle making, and other chores needed for the mission. At the time of the battle, this area was in ruin, with most of its rooms gone. It’s believed that it was here that the Alamo garrison kept their horses, and it’s also thought that there was a small cannon placement at its northeast corner.

The Big Tree

Today this courtyard is a peaceful garden. In the middle is a large Live Oak tree that visitors call, “the Big Tree.” This tree wasn’t there during the battle; it was brought and replanted there in 1912 by local resident Walter Whall. The tree was 40 years old, and already fairly big when it was moved and replanted there. It took four mules to pull the cart with the tree from Whall’s property to the Alamo. The most difficult aspect of the move was avoiding the power and telegraph lines on their way to the Alamo.

The Mission’s Well

Next to the “Big Tree” is an old dry well. This is said to be a modern reconstruction of the Mission San Antonio De Valero’s well that was located there. But there’s some debate as to the authenticity of this well. Some sources that I’ve read say that this is a non-historical feature, added much later. This theory is based on maps drawn by Alamo witnesses: Mexican Lieutenant Colonel José Juan Sánchez-Navarro and Alamo engineer Green B. Jameson, which doesn’t show well at that location. However, both of those maps were tactical battle maps, and showing a well would not have been needed.

In Mark Lemon’s book, the Illustrated Alamo, he shows a well at that location. Lemon had done considerable research and must be confident that there was indeed a well there. But again, what would the Alamo be without a little more controversy.

Shigetaka Shiga Monument to the Alamo’s Heroes

Photo by Scott Huddleston, San Antonio Express-News

Off in a corner of this courtyard is an often overlooked monument to the Alamo’s fall. This 4-foot tall gray granite stone has an inscription in Japanese, Chines, and English that reads, “To the Memory of the Heroes of the Alamo”

Dedicated on November 6, 1914, it is the oldest monument to the Alamo’s heroes. Personally created and donated by Japanese scholar, Shigetaka Shiga, it features a poem by Shiga himself. The poem compares the bravery of the Alamo defenders with those of the 16th century Siege of Nagashino Castle, which was another battle where a few hundred badly outnumbered defenders fought against thousands.

The Monument to the Gonzales “Immortal Thirty-Two.”

“Immortal Thirty-Two”

Photo by author.

There’s another monument in this courtyard you need to see. This is to the Gonzales “Immortal Thirty-Two.” On the evening of March 1, 1836, thirty-two men from the town of Gonzales rode through the Mexican lines coming to the aid of their fellow Texans. This monument is located on the courtyard’s north side.

As you look at the Long Barrack on the courtyard side, remember that these walls are reconstructions of the originals. However, archaeologists have recently discovered that when those reconstructions took place they did use the original foundations.

At the south end of the Barrack is how you enter the current Alamo museum. When the new museum is completed at the west wall, you can only wonder what will occupy this historic structure.

We’re now going the leave the old Convento courtyard and go over to the fort’s other courtyard.

The Northern Courtyard

The name for this courtyard varies depending on what source you read: In Mark Lemon’s book he refers to it as the Northern Courtyard, and Alan C. Huffines calls it the Cattle Pen in his book The Blood of Noble Men, and on the Alamo’s official website they refer to it as the Cavalry Courtyard (See map #13).

During the 1836 battle, it’s believed that this is where the defenders had indeed kept the cattle that fed the garrison, as Huffines stated. This courtyard was also one of the weakest areas of the fort, where its walls were only about four and a half feet high. Accounts state that during the battle this section was defended by a small 4-pounder cannon placed at its eastern corner. However, even with the low wall and small artillery piece, the defenders were able to hold off the attacking Mexicans, driving them further to the western end of the north wall.

The Statues of Heroes

Currently, the Cavalry Courtyard is displaying the “Statues of Heroes.” Here you’ll see six sculpted bronze statues of David Crockett, William Travis, Jim Bowie, Susannah Dickinson, holding her daughter Angelina, as well as other historical figures of the Texas Revolution. Sculpted by artists George Lundeen, Glenna Goodacre, Chris Navarro, Deborah Fellows, Enrique Guerra, Bruce Green, and others, they are part of “the Alamo Sculpture Trail,” which goes from the Alamo to the Briscoe Western Art Museum.

The wall that separates this courtyard, and the Alamo’s grounds, from Houston Street, isn’t where the fort’s original wall stood, that’s a foot further north on the street side. There’s a marker on the sidewalk that indicates the original boundary line.

As you leave the Northern Courtyard, look for the Wall of History (See map #14) next to the Alamo gift shop. The Wall of History is a long and colorful chronology of the Alamo’s history, beginning with its mission period.

The Alamo Gift Shop

Although the Alamo gift shop (See map #15) looks like an original building, it’s not. It was also built in 1937 for the Texas Centennial. It was first used as a museum on the history of Texas’s independence, and then later converted by the Daughters of the Republic of Texas (DRT) to the present gift shop.

Here’s a cute little story. In the 1985 Tim Burton movie, Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure, Pee-Wee Herman travels to the Alamo looking for his lost bicycle. He’s told that he’d find it in the Alamo’s basement. However, when he arrives, to his disappointment, he’s told that the Alamo doesn’t have a basement. Well, that’s not exactly correct, if you’re looking at all the property as the greater Alamo.

In 1992, the DRT hired G.W. Mitchell Construction to excavate a basement under the Alamo gift shop. Completed in 1993, this basement holds gift items, supplies, and an employee breakroom. And maybe, just maybe, there might be a bicycle somewhere down there too.

We’re now going to leave the courtyard areas and journey behind the Alamo church.

Slaughter Outside the Alamo

In my 2014 post, I told how the back of the Alamo church was completely different than it is today. During the battle, there wasn’t a roof, or windows, in fact, the wall of the church’s apse was considerably lower. It was in the ruined church’s apse that a platform had been built, at about twelve feet in height. Atop this platform were placed three cannons. This allowed the defenders to cover the ground behind the fort very effectively.

Although not usually pointed out, those cannons on the platform and the area behind the Alamo’s church (see map #16) would play both a heroic and tragic part in the Alamo’s battle story.

On the morning of March 6th, 1836, Santa Anna’s army began their attack on the Alamo. Colonel José María Romero’s mission was to storm the east side of the Alamo. Leading 300 men, Romero charged the rear of the church and the lowed walled Convento and northern courtyards. Here he encountered heavier than expected resistance from the defender’s small arms and cannon fire. This caused Romero to fall back and also drift to the north, where he would eventually mix with the forces attacking the Alamo’s north walls.

However, even with Romero’s men now to the north there still was a Mexican presence in that area. At a short distance from the fort was the Dolores Cavalry, patiently waiting for their time. Their mission was to apprehend any defender who tried to escape. And that time soon came.

As Santa Anna’s men worked their way southward through the fort, a group of defenders tried to make a break for it through a narrow opening between the church’s southwest corner and the wooden palisade. As they ran to the southeast across the open field they soon met the Mexican cavalry.

Even with supportive fire from the cannons at the back of the church, these men were soon cut down. Men on foot have little chance against mounted cavalry. It should also be said, that although these defenders tried to escape the massacre, accounts by the Mexican’s say they fought bravely to the end.

This battle site is currently being used for living history encampments and is where the Alamo Hall and the new Exhibit Hall are located.

In my post, “Where are the remains of the Alamo’s Heroes?” I’ll present an idea on the possible location of the mysterious Alamo defenders’ third funeral pyre.

We’ll now walk along the south side of the Alamo church, heading back to its front. Running along the back of the church, you’ll see what looks like a water-filled ditch. This is what remains of the Acequia Madre, also known as the Acequia del Valero or Acequia del Alamo. This was part of a network of irrigation canals that watered the fields when the Alamo was a mission. This system of canals was so extensive that archaeologists have found traces of it in the parking lot of St Joseph Church on E. Commerce Street.

As you continue walking along the south side of the church, you’ll see on the left the new Alamo Exhibit Hall; this was formally the DRT library. Be sure to check out what exhibit is being presented there.

The Alamo Cannon Display

Just before you reach the front of the church, you’ll walk under a stone arcade. Although this may look like an original structure of the Alamo, it’s not. It was built in the 1930s by the DRT. When I was there in 2018, this arcade was used as a queue for those waiting to enter the Alamo church. But today it’s used to display newly restored cannons, of which many were used in the Battle of the Alamo by its defenders.

As you look at these cannons, you’ll notice that some are damaged. This is due to the Mexican soldiers making them inoperable after the Battle of San Jacinto, so they couldn’t be used by the Texians. Also, many of these cannons were the ones discovered buried by Samuel Maverick, at where the Hotel Gibbs sits today.

In Front of the Alamo Church

There are quite a few spots around the front of the Alamo church (see map #17) that I’ll be pointing out. The first is the place where David Crockett and his men from Tennessee defended. They manned what was a long wooden palisade, which ran from the southwest corner of the church to the southeast corner of the main gate Low Barrack building; this is often referred to as, “Crockett’s Palisade”(See map #18).

Photo by author.

There was another, often overlooked, building and wall that also helped to close off this area in front of the church. The building angled north off of the east side of the Low Barrack and served as the garrison’s kitchen during the battle. From that building, running north to the Long Barrack was a six-foot-high stone wall (See map #19).

This wall and building, along with the wooden palisade and Convento wall, would have separated this section of the fort from the rest of the compound. It may have been this area that Alamo survivor Susannah Dickinson was referring to as, “the little fort,” in an interview.

To see where the wall and the palisade were, cross over the closed E Alamo Street and look back toward the church. There on the street, you’ll see two lines, one going to the church and the other to the Long Barrack, this marks their locations.

We’re now going back to the church and the large rectangle grassy area (See map #20) in front of it. This is another historical spot that is mostly overlooked and has nothing to do with the battle. I was told that this grass area was installed by the DRT to remember the mission’s Priests and Indians who were buried there when it was the mission’s “Compo Santo,” or cemetery. Mission records show that nearly 1,000 burials had taken place on the grounds of the Alamo. After the mission was secularized and abandoned in the late 1700s, it’s not recorded if those remains were ever relocated, or simply, forgotten.

Near the church’s front door, on the right side (see map #21) you’ll see a metal plaque in the plaza stones that read,

LEGEND STATES THAT DAVID CROCKETT (BORN AUGUST 17, 1786) SACRIFICED HIS LIFE FOR TEXAS LIBERTY HERE IN DEFENSE OF THE ALAMO ON MARCH 6, 1836.”

Although this may not be the exact location where Davy Crockett died, it is in the general area described by Susanna Dickinson, as she left the church after the battle.

“I recognized Colonel Crockett lying dead and mutilated between the church and the two story barrack building, I even remember seeing his peculiar cap lying by his side.”

Susanna Dickinson

As you stand there close to the church’s façade, look closely. Those pockmarks you see on the façade are from musket balls, another sign of the terrible fighting that took place there.

Before we leave this area in front of the church there’s another marker I want you to look for. This marker also has a thin brass rod embedded near it (See map #22). The marker says that it was at that location that Travis drew his legendary line in the sand. However, Travis’s line continues to be more of a myth and legend than a historical fact. And if Travis’s noble event did take place, there is no record that it happened at that location.

Sites on the South End of the Alamo Compound

The Low Barrack and the Alamo’s main gate

We’re now going to leave the front of the church, and walk back to where those two before mentioned lines met. There, running across Alamo Plaza is a large rectangular, stone bordered, grassy area (See map #23). This is where the building was known as the Low Barrack once stood.

The Low Barrack measured 131-feet long and 17-feet in height, with walls from two to two and a half feet thick. The building had three rooms, with the eastern room being, what is believed, where James Bowie was killed (See map #24). The Low Barrack also held the fort’s main gate (See map #25) and also made up most of the Alamo’s south wall.

Photo by author.

Just outside the main gate was a structure that helped guard the gate. This was a wooden and earthen lunette (See map #26). This lunette was destroyed by the Mexican army, along with the fort’s connecting walls and cannon, after their defeat at San Jacinto.

Although this lunette was indicated on the map drawn by Mexican Officer José Sánchez-Navarro, it wasn’t believed to have been very big or important. However, in 1988 an archaeological dig at the site revealed that this lunette was most likely very substantial in size and importance. Although the exact dimensions still need to be uncovered by future explorations, it’s believed that it ran roughly seventy-two or seventy-three feet to the south of the Low Barrack, and about sixty-three feet east to west.

Find the marker indicating where the fort’s main gate was and take a few steps south, you’ll then be standing where the lunette was located.

Always New Things to See

This ends my tour of the historic Alamo compound. However, as I said, this post is based on my 2018 visit, and although I try to keep this post updated, things have been changing pretty fast at the Alamo.

Revealing the Alamo

As I stated in my introduction to this post, the purpose in my writing these walking tours was to help visitors discover the hidden Alamo battlefield. But now under the direction of the Texas General Land Office (GLO) and the Alamo Trust, Inc. (ATI) things are beginning to change on the site of the 1836 Alamo compound. Thanks to their efforts the Alamo is beginning to be revealed.

With these two new exhibits, visitors can now begin to see the scope and size of what was the Alamo.

The Losoya House and 18-Pounder Cannon Exhibit

On April 16, 2021, at what was the southwest corner of the Alamo fort (See Sites on the West Side of the Alamo Compound above) the 18-Pounder/Losoya House exhibit was unveiled. This exhibit sits on the exact site of the original building of 1836. The exhibit features a reproduction of the Losoya house gun platform which held the Alamo’s largest cannon, its 18-Pounder. In addition, the ATI had a reproduction of that famous historic cannon constructed, which now sits atop the structure as it did during the battle, ready to fire in defiance to Santa Anna’s demands for surrender.

Unlike the defenders of the Alamo, who had to walk up an earthen ramp, visitors to this exhibit can easily walk-up stairs or take an elevator to its top.

The Palisade Exhibit

In December of 2021, the second outdoor exhibit on the Alamo grounds was opened. This exhibit is a partial re-creation of the wooden palisade that originally spanned the area between the church and the Low Barrack. This palisade is often referred to as “Crockett’s Palisade,” due to the belief that this is the area of the fort that David Crockett defended (See In Front of the Alamo Church above).

This display is constructed of vertical cedar posts, a hardwood ramp and decking, as well as a replica of a 4-pounder bronze cannon. The exhibit sits approximately where the original palisade stood in 1836.

One thing I can say for sure, now under the GLO they’ll be many more changes coming.

I hope that this post will help you to navigate around what was the Alamo of 1836.

And as I stated above, the Alamo under the direction of the Alamo Trust and the General Land Office are constantly adding new exhibits and events. For more information check out www.thealamo.org.

With my next posting, we’ll explore those historical sites that are beyond the walls of the Alamo.

Sources used:

“18 Pounder Cannon.” The Alamo, The Alamo, http://www.thealamo.org/visit/whats-at-the-alamo/18-pounder-connon. Jan. 2022.

“18-Pounder Losoya House Exhibit.” DO210, DO210, do210.com/events/2021/4/16/18-pounder-losoya-house-exhibit. Jan. 2022.

“Alamo Palisade Exhibit Grand Opening on December 17.” The Alamo, The Alamo, 10 Dec. 2021, www.thealamo.org/alamo–trust/pressroom/alamo-palisade-exhibit-grand-opening-on-december-17.

“History Comes to Life With Outdoor Alamo Exhibit on April 16.” The Alamo, The Alamo, 9 Apr. 2021, www.thealamo.org/alamo-trust/pressroom/history-comes-to-life-with#:~:test=History%20will%20come%20to%20life,Alamo%20Plaza%on%20April%2016.

Huffines, Alan C. Blood of Noble Men, The Alamo, Siege & Battle. First Edition, Eakin Press, 1999.

Kirkpatrick, Dean. The Alamo Story and Battleground Tour. First Edition, NDK Publications, 2013.

Lemon, Mark. The Illustrated Alamo 1836, A photographic Journey. State House Press, 2008.

Nelson, George. The Alamo, An Illustrated History. Third Revised Edition, Cenveo Printing Company, 2009.

“Palisade.” The Alamo, The Alamo, http://www.thealamo.org/visit/whats-at-the-alamo/palisade. Jan. 2022.

Texas Public Archaeology Network. “1719 Acequia Madre and the Alamo Dam.” Texas State, Texas State University, txpan.txstate.edu/Projects/History-of-the-Witte-Memorial-Museum/1719-Acequia-Medre.html. Feb. 2022.

That was really well-done, Ron. There were some landmarks I missed the last time I was there. I’ll be sure to look for some of these sites the next time I’m in San Antonio.

LikeLike

Than you Phil. For your ext visit I’ll be posting Part 2 in my walking tour series, Beyond the Alamo’s Walls. And I’m currently writing part 3 that will deal with the funeral pyres and where the defenders remains my be. Thanks again

LikeLike

Thank you for sharing. I visited this past December and it helped me realize about where everything was during the real battle.

LikeLike

Thank you so much. That was my goal.

LikeLike

Fantastic! And, much more to come. I’m 72, & hope to visit when finished. Gotta stay healthy.

LikeLike

Thank you. I’m 74, an plan on going back soon.

LikeLike