In A Daunting Task, the first post of this series, I told how in the aftermath of the pre-dawn battle of March 6, 1836, Santa Anna’s soldiers and Béxar townspeople gathered up the bodies of the Alamo defenders and dragged them to the peaceful cottonwood-lined avenue known as the Alameda. There, the bodies were stacked and cremated on two large pyres of wood: one on the north side and one on the south side of that road.

In Part Two, The Alameda, I identified where that avenue would have existed on today’s E. Commerce Street.

In Part Three, The North Pyre, and Part Four, The South Pyre, I pinpointed the probable locations on E. Commerce of those two pyres.

Now, with this post, The Funeral, I’ll examine the event that took place on February 25, 1837, which will answer some of the nagging questions that surround what became of the Alamo defenders’ remains.

My primary sources for this post were Col. Juan N. Seguin’s official report to his commander, Brig. Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston, dated March 13, 1837, and the Telegraph and Texas Register newspaper article dated March 28, 1837. Between these two accounts, we get a picture of what occurred at the February 25, 1837, funeral for the fallen Alamo heroes.

To set the stage, we’ll begin back in 1836, three months after the cremation, as eyewitnesses describe the terrible condition of the defender’s remains.

The Ashes Floated Upon the Breeze

Eyewitnesses to the burning of the Alamo defenders reported that after the flames had died out, all that remained of the bodies were a few fragments of bone scattered among the still-smoldering ash.

Dr. John Henry Bernard, who was saved from the massacre at Goliad to care for the Mexican soldiers wounded at the Alamo, wrote in his journal on May 25, 1836, three months after the cremations, what he found at the pyre sites: “The bodies had been reduced to cinders; occasionally, a bone of a leg or arm was seen almost entire. Peace to your ashes!”

Dr. John Sutherland, one of the first couriers to leave the Alamo on February 23, 1836, provides a more comprehensive description of the condition of the defenders’ remains in his 1860 memoir The Fall of the Alamo. Dr. Sutherland tells, “The pile being consumed, much of the bones of the Texians, as remained, lay for nearly a year upon the ground, while the ashes floated upon the breeze that found the sacred spot. There was no friend to collect and preserve these relics of the brave. They were scattered about on the grounds unnoticed by an ungrateful populace who knew not how to appreciate their value.” It’s worth noting that some of Dr. Sutherland’s accounts have become somewhat suspect to historians. However, his description of the condition and neglect of the defender’s remains aligns with other accounts.

These narratives paint a ghoulish and gruesome picture of how the bones of the fallen Alamo heroes lay on the ground, open to the animals and the elements for a year, until another courier from the Alamo, and a hero of the Battle of San Jacinto, would finally award the honors of war to those who fell at the Alamo. And that was Juan Nepomuceno Seguin.

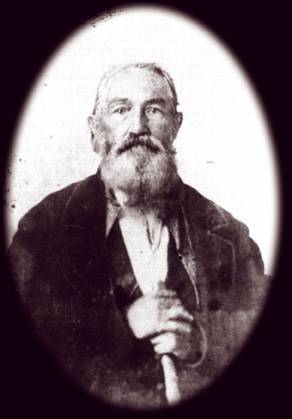

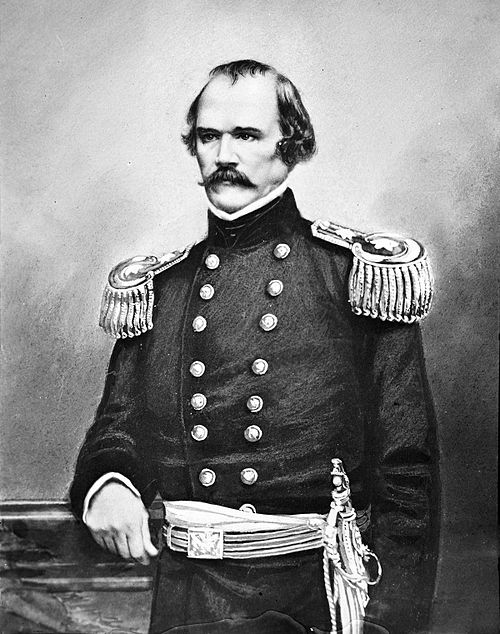

Juan Nepomuceno Seguin

Juan Nepomuceno Seguin played a pivotal role in the Texas Revolution and is the principal subject of this post. For this, we should know a little bit about this Texas Patriot.

Juan Nepomuceno Seguin was born in San Antonio de Béxar on October 27, 1806. Seguin was active in the political affairs of Béxar, being elected an alderman in 1828 and then its alcalde (mayor) in 1833. When hostilities broke out between Texas and Mexico, Seguin joined the Texas cause.

Commanding the Tejano forces, he led his men in the Battle of Concepcion and the Siege and Battle of Béxar. On February 23, 1836, Seguin and his Tejanos joined Travis in the Alamo. Two days into the siege, on February 25, Travis called on Seguin to carry a message to General Sam Houston, thus saving him from the battle and massacre of March 6.

On April 21, 1836, Seguin played a decisive role in the Battle of San Jacinto, which ultimately led to Texas gaining its independence.

In the early part of 1837, Seguin, now a Colonel in the Army of the Republic of Texas, was assigned to command the Texas forces in his hometown of San Antonio. There, Brig. Gen. Felix Huston instructed Seguin to gather up the remains of the Alamo defenders and give them a proper “Honors of War” burial.

Seguin took this undertaking solemnly, having lost both friends and family members at the Alamo. This personal connection added a profound sense of duty and reverence to his task.

On February 25, 1837, a year after he had left the Alamo to deliver Travis’s message, Col. Juan N. Seguin assembled a company at the cremation sites to finally give the Alamo defenders the honor they deserved.

“The Ashes Were Found in Three Heaps”

From what I could find, the March 13, 1837, report by Col. Juan N. Seguin to his commanding officer, Brig. General Albert Sidney Johnston and the Telegraph and Texas Register newspaper article of March 28, 1837, are the earliest accounts of what occurred at the February 25, 1837, funeral of the Alamo defenders.

Of these, Col. Seguin’s is the most significant. This is due to it being his firsthand account of what took place at the funeral of the Alamo defenders. And since his report was written just a month after the event, what happened that day would still be fresh in his mind, unlike his more controversial letter, written fifty-two years later, when he was 83.

The Texas Telegraph and Register newspaper’s article mirrors Col. Seguin’s account, suggesting that Seguin’s report served as the foundation for the newspaper’s article. However, there are a few notable differences between these two narratives.

Both Col. Seguin’s report and the Texas Telegraph and Register article begin their narratives at the site of the defender’s ashes. Col. Seguin describes what he saw: “The ashes were found in three heaps,” while the Texas Register’s version varies slightly, “The ashes were found in three places.” Although these differences may not seem very significant, they’ve sparked some controversy.

Col. Seguin’s narrative continues with this description: “I caused a coffin to be prepared neatly with black, the ashes from the two smallest heaps were placed therein…” However, the Texas Register’s version provides more detail. The newspaper article reads, “The two smallest heaps were carefully collected, placed in a coffin neatly covered in black, having the names of Travis, Bowie, and Crockett engraved on the inside of the lid.” Details again strangely absent from Seguin’s report.

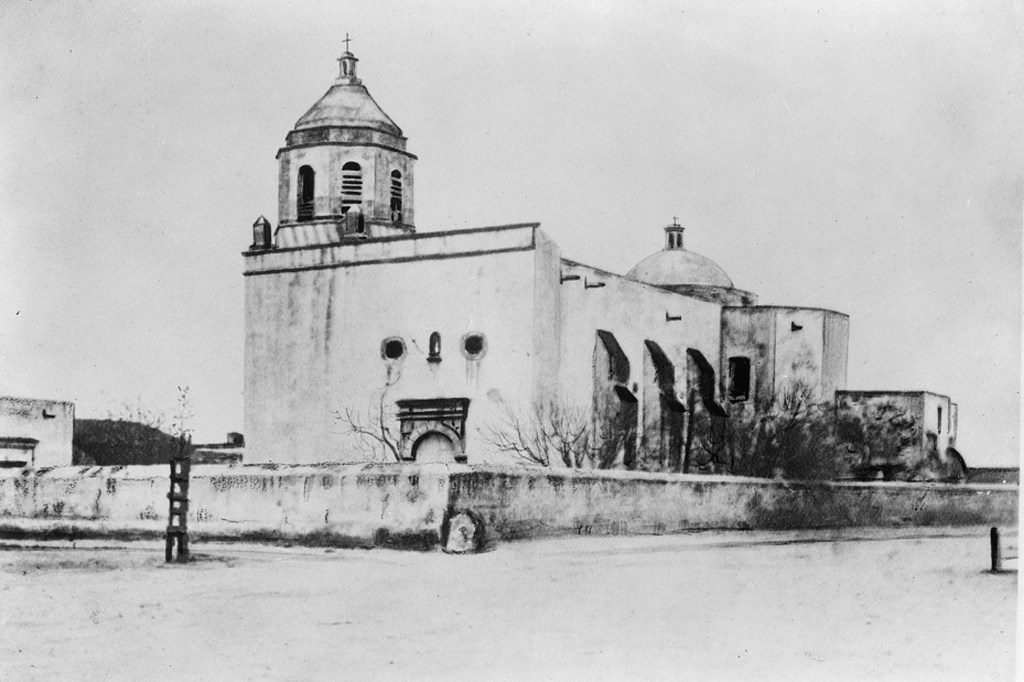

With the ashes from the two smallest heaps collected and placed in the coffin, the accounts tell how the procession carried the coffin to the Béxar Parish Church, today’s San Fernando Cathedral. There, the Texas Register again adds more detail on what occurred than does Col. Seguin. The newspaper article reported: [The coffin was] “carried to Béxar and placed in the parish church, where the Texas flag, a rifle, and sword were laid upon it…” Once again, details absent from Col. Seguin’s account. So why would that be?

Col. Seguin may have omitted those details because he felt they were unnecessary for his official military report. Or it may have been the embellishments of the Texas Register’s uncredited writer. We may never know which is correct.

Besides these differences in the descriptions between the two narratives, there’s another issue that has caused confusion and speculation among Alamo historians. And that is, despite the detailed narratives provided by eyewitnesses in the years following the defenders’ cremation, none of those accounts provides the specific location of where they found the pyres. This has led some to place the pyres and the remains of the defenders in other locations, rather than just on the Alameda. So, why would something as important as the location of the pyres be excluded from those accounts? And that answer could be very straightforward.

It Was Common Knowledge

In the early 1800s, the cottonwood-tree-lined Alameda Avenue was well-known and well-traveled. In fact, it was the western end of the Gonzales Road, the main route that connected San Antonio de Béxar to the American colonies. Anyone leaving or entering Béxar would have had to take that road, where they would have undoubtedly seen what remained of the funeral pyres. Therefore, the location of the pyres would have been common knowledge, and the writers felt no need to include that information in their accounts.

And yet, some historians have criticized Col. Seguin’s report for not explicitly stating the location from where the defenders’ remains had been gathered and later buried. But this assumption isn’t entirely correct.

The Principal Avenue

Although the narratives of Col. Seguin and the Telegraph and Texas Register give a detailed description of the funeral procession’s return to where the ashes had been gathered, their use of specific terms makes it difficult to understand the places they were referring to. However, I believe I’ve translated what they were talking about. I’ll explain.

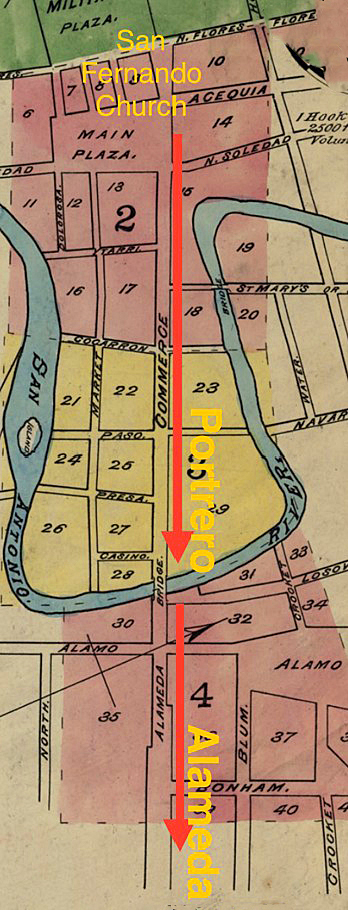

In their accounts, they tell that at 4 o’clock in the afternoon of February 25, 1837, the procession of mourners left San Fernando Church with the coffin containing the ashes of the Alamo defenders and solemnly began their journey back to where they’d been collected. Here, Col. Seguin describes how “the procession then passed through the principal street of the city and crossed the river.” So, what was the “principal street” Seguin was referring to?

The principal street of a town would be its main street. In 1837, Portrero Street was Béxar’s primary or principal street. It ran west to east from the city’s west side, past the Main Plaza and the San Fernando Church, ending at the San Antonio River, where a small bridge existed. So, Seguin was undoubtedly referring to Portrero, which is now part of E. Commerce Street.

Once the funeral procession had crossed the San Antonio River to its east side, Col. Seguin tells, “passing through the principal avenue, we arrived at the spot whence part of the ashes had been collected.” This is also reported in the Texas Register, “crossed the river, passed through the principal avenue on the other side, and halted at the place where the first ashes had been gathered.” Both of these accounts describe the location of the defenders’ ashes as being on the “principal avenue.” But what was that principal avenue?

It’s very telling that these two accounts use the term “avenue” rather than street, as they did with Portrero Street. To understand why this is significant to our search, we need to know the definition of an avenue. An avenue is usually a wide, tree-lined road. And the only wide, cottonwood tree-lined road on the east side of the San Antonio River at that time was the Alameda.

Let’s now review the routes taken by Col. Seguin and the funeral procession on February 25, 1837. Col. Seguin and his company of mourners gathered at the three Alamo defenders’ ash piles on Alameda Avenue. There, they honorably collected the ashes from the two smallest piles and placed them in a specially constructed coffin for this event. Carrying the coffin, with the defenders’ remains, the funeral procession proceeded to the San Fernando Church, most likely by the way of Portrero Street. At the church, a service was held honoring the Alamo heroes.

Then, at 4 o’clock that afternoon, the procession took up the coffin, leaving San Fernando Church, and they proceeded back east along Portrero Street, arriving at the San Antonio River, where they crossed to its east side by a small footbridge.

Once on the east side, the procession continued east on Alameda Avenue, stopping back at the site of the funeral pyres and the defenders’ remains. There, the military Honors of War were given.

On this 1877 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, Sheet 1, of San Antonio, I’ve marked the route the funeral procession took.

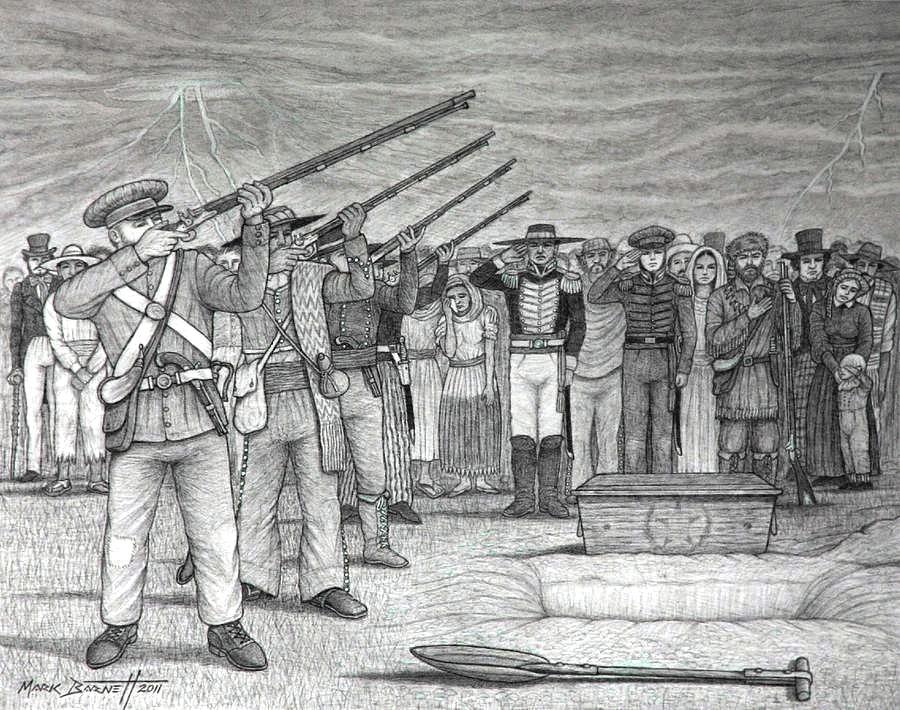

The Honors of War

Now gathered on the Alameda, at the site from where they’d collected the ashes, after nearly a year of neglect, Col. Juan N. Seguin and his company of mourners began to give the military Honors of War that was due the brave defenders who fell at the Alamo.

Col. Seguin describes what took place, “…at the spot whence part of the ashes had been collected, the procession halted, the coffin was placed upon the spot, and three volleys of Musquetry was discharged over it by one of the Companies, proceeding onwards to the second spot from whence the ashes were taken where the honors were done…” The Telegraph and Texas Register gives a similar account, “…at the place where the first ashes had been gathered; the coffin was then placed upon the spot and three volleys of musquetry were discharged by one of the companies; the procession then moved on to the second spot, whence part of the ashes in the coffin had been taken, where the same honors were paid.”

With the honors completed at the sites of the two smaller ash heaps, the accounts then tell how the procession of mourners carried the coffin to the larger third pile of ashes, which Col. Seguin referred to as “the principal spot and place of interment,” with the Telegraph and Texas Register adding, “where the graves had been prepared.” There, the pallbearers place the coffin on top of the large pile of ashes.

At that time, Col. Seguin gave a eulogy to the Alamo’s fallen in his native Castilian language. This was then translated into English by a Major Thomas Western. Col. Seguin doesn’t mention in his report the remarks he made that day; however, the Telegraph and Texas Register includes what Col. Seguin purported to have said in their article.

After the eulogies, Col. Seguin describes what occurred next. “The coffin and all the ashes [of the third heap] were interred [buried], and three volleys of Musquetry [sic] were fired over the grass by the whole Battallion [sic].”

With the honors now paid, Col. Seguin concludes his report with, “We then marched back to quarter in the City [Béxar] with Music and Colors Flying.” This ended the funeral services for the Alamo defenders.

The Place of Internment

With statements of “the principal spot,” “the place of Internment,” “where the graves had been prepared,” and “the coffin and all the ashes were interred,” leave little doubt that the cremated remains of the Alamo martyrs were buried at the location of the largest of the three heaps of ashes on the Alameda. But where was that?

In my next post, The Place of Internment, I’ll dig deep into the accounts that describe where the cremated remains of the Alamo defenders had been buried, and where that spot would be today.

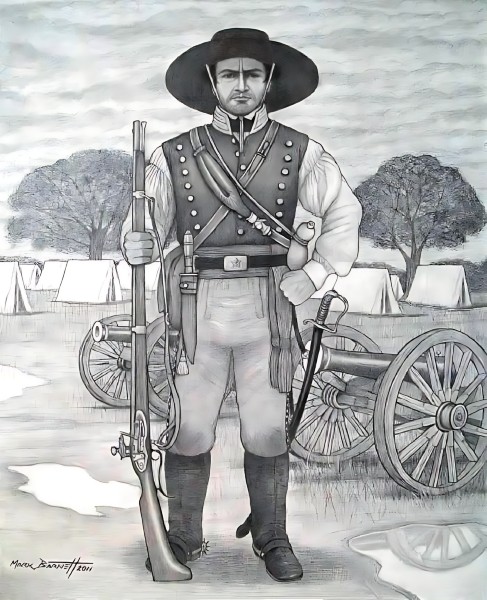

I’d like to give a special THANK YOU to artist Mark Barnett for allowing me to feature his artwork in this post. Those images gave more depth to my words.

Sources used for this post:

Hansen, Todd. “Juan Seguin, letter, March 13, 1837.” The Alamo Reader, A Study in`History, first Addition, Stackpole Books, 2003, pp. 200-201.

Hansen, Todd. “Juan Seguin, newspaper account, 1837.” The Alamo Reader, A Study in History, frist Addition, Stackpole Books, 2003, pp. 201-203.

A truly mindblowing read, the work you did was inspiring and historic. I hope every American citizen reads these articles.

LikeLike

Thank you

LikeLike