“The other pyre, which was of equal width, was about eighty feet long and was laid out in the same direction, but was on the opposite side and on property now owned by Dr. Ferdinand Herff Sr., about 250 yards southeast of the first pyre, the property being known as the site of the old Post or the Springfield House.”

CHARLES MERRITT BARNES, FROM HIS MARCH 26, 1911 SAN ANTONIO EXPRESS ARTICLE, BUILDERS SPADES TURN UP SOIL BAKED BY ALAMO FUNERAL PYRES

In the mystique of the Alamo, the most often cited locations where the Alamo defenders’ bodies were cremated were on two funeral pyres built on the north and south sides of the tree-lined boulevard known as the Alameda, today’s E. Commerce Street.

In my last post, I presented where I believe the north funeral pyre had been. With this post, I’ll attempt to discover the South Pyre’s location.

Those who study the Alamo know all too well that nothing in its recorded history is 100% accurate. It takes a lot of research and piecing together documented accounts. And so, for this post, as I have with my other writings, I’ll use eyewitness accounts, historic Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, and the Google satellite map of E. Commerce in my investigation. In addition to these and other reliable sources, I’ll also use the 2022 study, An Archaeological Review of Reported Human Remains at Alamo Plaza and Mission San Antonio de Valero. This in-depth study was conducted by the Center of Archaeological Research for the City of San Antonio. Chapter 7: The Mystery of the Alamo Funeral Pyres: 185 Years of Searching for that Hallowed Ground was extremely valuable for me in researching this post.

I’ll begin with the site’s history.

The History of the South Pyre Site

As with the land on the north side of the Alameda, the land on its south was also mainly undeveloped farmland at the time of the Battle of the Alamo. But by the late 19th century, these areas began to be transformed by development.

As the Alameda evolved from a peaceful cottonwood-lined boulevard into the busy commercial East Commerce Street, the land on its south side would be occupied by more than 200 city blocks connected by over sixty streets. Commercial buildings began to spring up within that area, including the Post or Springfield House.

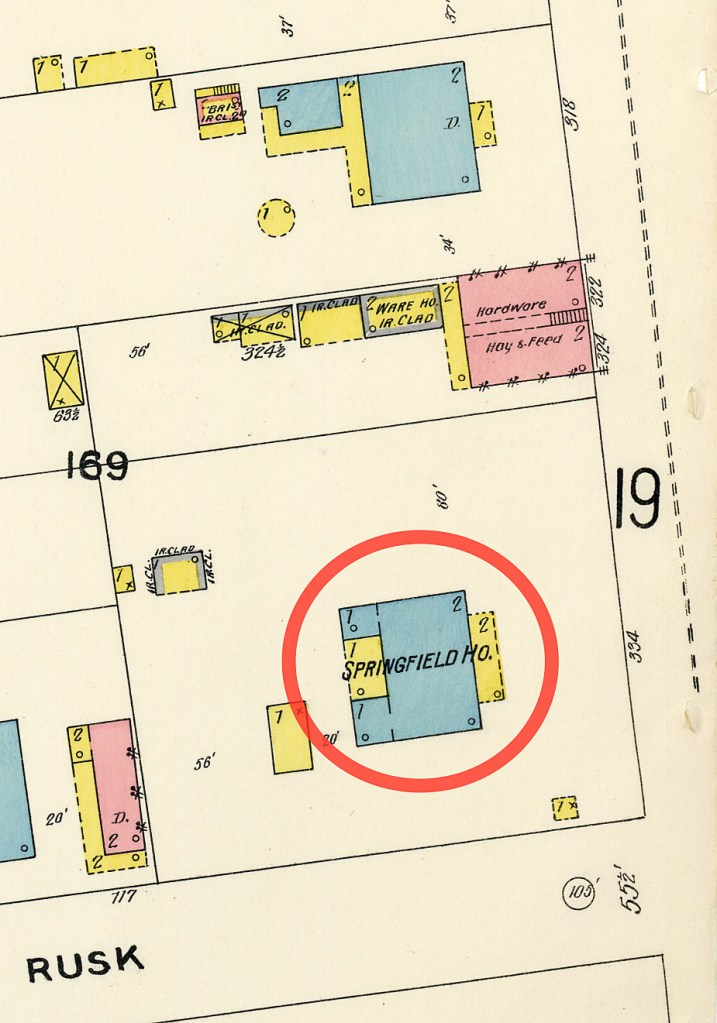

In 1852, the Post family constructed a two-story boarding house on the southwest corner of E. Commerce and Rusk Streets. This would be known as the Post and then later the Springfield House. On Sheet #17 of the 1896 Sanborn Fire Insurance map of San Antonio, the building on the southwest corner of E. Commerce and Rusk Streets is shown, with “SPRINGFIELD” written on it (Figure #1).

As with the Ludlow and Moody buildings, the Post/Springfield House would be used by eyewitnesses to the cremation of the Alamo defenders as the location of the south funeral pyre.

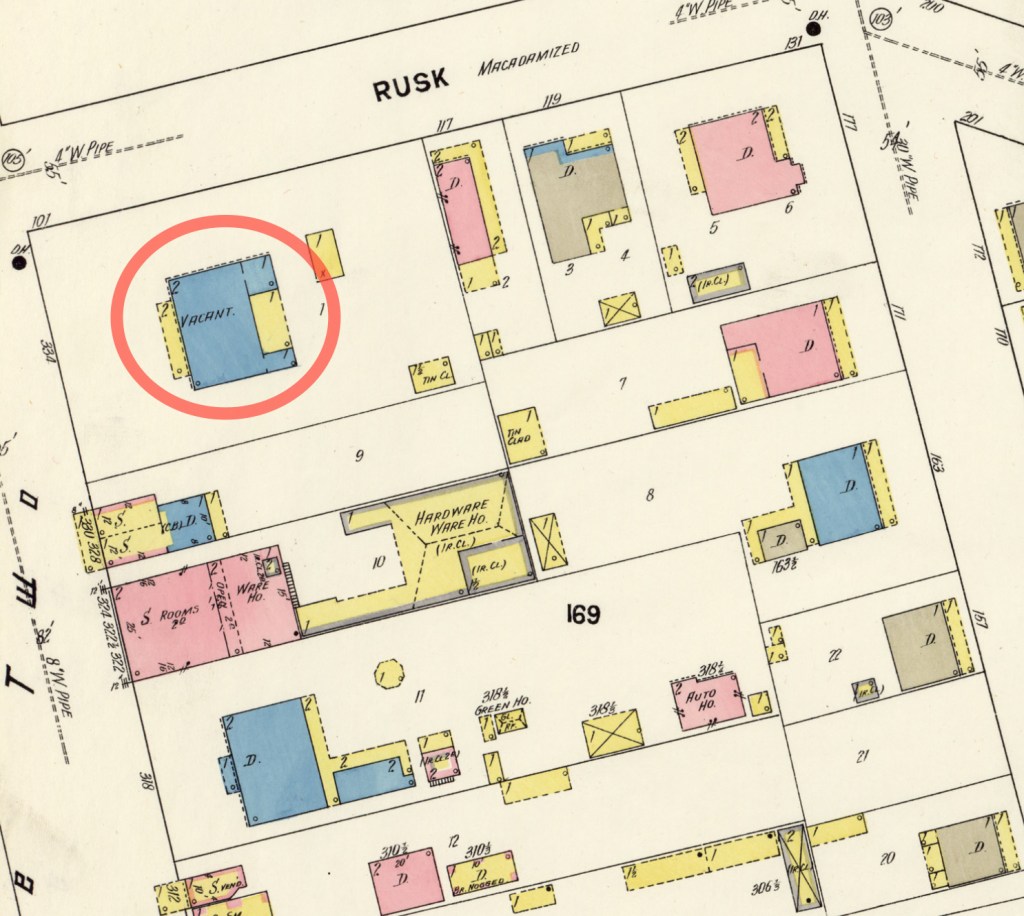

Historically, the Post/Springfield House would be used as an Army Hospital, an Episcopal boarding school for girls, and finally, a general boarding house. But by 1912, the building was described by historian and reporter Charles Barnes as, “The old house stands ramshackle and deserted on East Commerce Street, just a little beyond St. Joseph’s church.” Barnes’s observation is confirmed on Sheet #236, Volume 3, of the 1912 Sanborn map, which shows it as “vacant” (Figure #2).

As with the site of the north pyre, Barnes made a dire prediction on the fate of the Springfield House and the south pyre when he wrote, “In a short time, it will be torn down, a modern business will take its place; it will pass away and be forgotten.” Barnes was correct in that the Springfield House would be torn down, but the site of the Alamo defender’s south funeral pyre would not be forgotten, at least for a time.

Dr. Ferdinand Herff Sr. purchased the Springfield property, and in 1918, he demolished the old vacant house and constructed a modern multi-story brick commercial building on the site. He named his building the M. Halff & Bro. On March 6, 1918, in a grand ceremony, Adina De Zavala installed marble tablets on the Moody and Halff Buildings, recognizing them as the sites of the two funeral pyres of the Alamo defenders. I’ve circled De Zavala’s tablet in this 1941 photograph of the Halff Building (Figure #3).

For the next fifty years, the Halff Building, with the marble tablet, would stand as a witness to the fate that befell the bodies of the Alamo’s defenders. However, this would drastically change in the mid-1960s.

To commemorate San Antonio’s 250th anniversary of founding, the city undertook a massive World’s Fair project called HemisFair ’68. The site of HemisFair encompassed over 92 acres, bordered by E. Commerce Street on the north, Bowie Street on the east, E. Market Street is on the south, and S. Alamo Street is on the west.

Most of the land needed for HemisFair was acquired through eminent domain. The homes, businesses, and streets on the fair’s site were eliminated en masse. The HemisFair website states that twenty-four historic buildings were saved from the wrecking ball. But sadly, the Halff Building, with De Zavala’s tablet, was not one of them. The Halff Building was demolished in 1968 to extend the Riverwalk (Paseo del Rio). To add to this tragedy, the demolition of the Halff Building was before the Antiquities Code was adopted, so no archaeological investigations were conducted.

However, there’s one slight positive to this story. Unlike the tablet on the Moody building, which disappeared, Mr. and Mrs. William Sinkin, owners of the Halff Building, removed De Zavala’s tablet for safekeeping.

This weather-worn historical marker was mounted on the low rock wall along the south side of E. Commerce Street on March 6, 1995 (Figure #4).

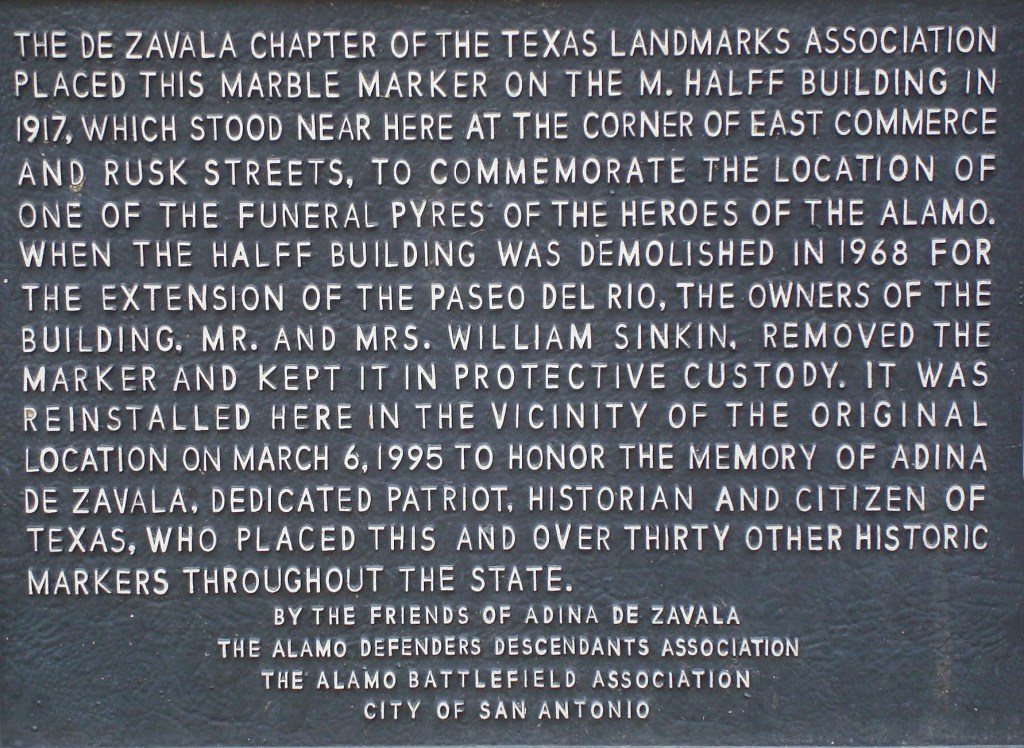

Mounted next to De Zavala’s tablet is a bronze plaque that tells the story of the funeral pyre and De Zavala’s tablet. It reads:

The De Zavala Chapter of the Texas Landmark Association placed this marble marker on the M. Halff Building in 1917, which stood near here at the corner of E. Commerce and Rusk Streets, to commemorate the location of one of the funeral pyres of the Heroes of the Alamo. When the Halff Building was demolished in 1968 for the extension of the Paseo del Rio, the owners of the building, Mr. and Mrs. William Sinkin, removed the marker and kept it in protective custody. It was reinstalled here in the vicinity of the original location on March 6, 1995, to honor the memory of Adina de Zavala, a dedicated patriot, historian and citizen of Texas, who placed this and over thirty other historic markers throughout the state.

By The Friends of Adina De Zavala

The Alamo Defenders Descendants Association

City of San Antonio

This plaque states that it’s located “in the vicinity of the original location.” In this post, we’ll find out how accurate that statement is.

Locating the South Pyre

Unlike the search for the north pyre, my quest to find the south pyre was much more accessible. The Springfield House, the point of reference for the location of the south pyre, is well-identified on the Sanborn maps of 1896, 1904, and 1912. Also, while the Springfield House was easily found on the southwest corner of E. Commerce and Rusk Streets, the north pyres Ludlow and Moody Buildings were in the middle of the block, which made it harder to pinpoint their locations.

In addition, the Sanborn map I selected, the Sanborn 1912, Volume 3, Sheet #236, has the complete length of the south side of E. Commerce from the still-in-existent S. Alamo Street to Rusk Street. This differs from the multiple maps I assembled to find the north pyre.

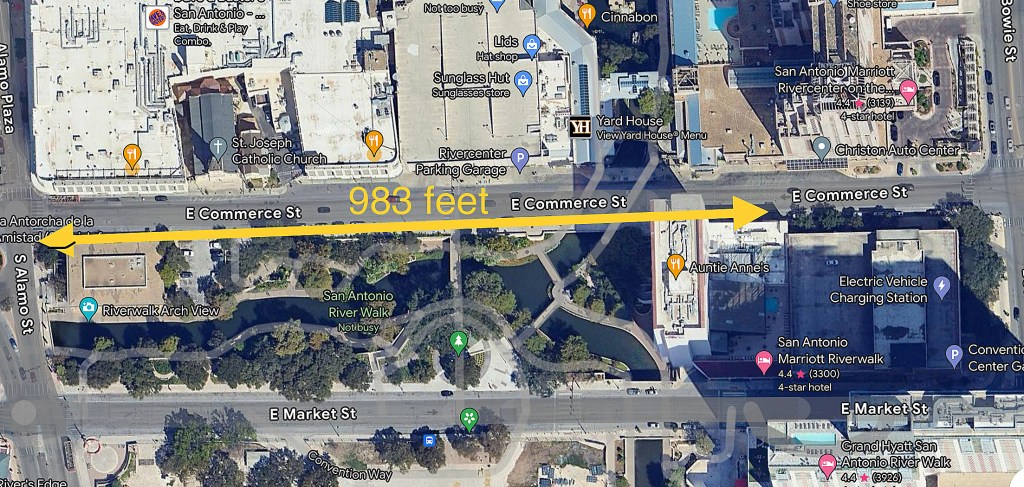

I began my search for the Springfield House with the scale on Sheet #236. Starting from S. Alamo Street, I measured east along E. Commerce to the Springfield House’s address of 334 E. Commerce. This came to 983 feet (Figure #5).

Taking this information, I used the measuring tool on the Google map of E. Commerce and went from S. Alamo Street, east 983 feet (Figure #6).

This places the Springfield House and the site of the south pyre on the west side of the Marriott Riverwalk Hotel complex and parking garage (Figure #7).

From what I can ascertain, this was the location pointed out by witnesses as the site of the south pyre. Except, Charles Barnes added a twist of uncertainty.

The Mystery of the 250 Yards

In his 1911 San Antonio Express newspaper article Builders’ Spades Turn Up Soil Baked by Alamo Funeral Pyres, Barnes wrote that the distance from the north pyre to the south pyre was “about 250 yards southeast of the first pyre.” If I’m reading this correctly, that would have separated the pyres by two-and-a-half football fields. And that doesn’t seem right.

Looking at the Sanborn maps, the Ludlow House and Springfield House are nearly across from each other on E. Commerce Street. Barnes would have been aware of this, having multiple witnesses point out those locations to him. So, what’s the answer to this mystery? Here are a couple of thoughts that I came up with.

It was an uncorrected typo in the article. Barnes could have meant 250 feet, not yards. To test this possibility, I measured from the Margaritaville Restaurant, where I placed the north pyre, southeast across E. Commerce Street, to where I put the Springfield House and the south pyre. That came to 243 feet (Figure #8). So that may be what he meant. There’s another possibility.

In 1912, Barnes reported the Springfield House/south pyre’s location as “on East Commerce, just a little beyond St. Joseph’s Church.” However, using his 250 yards between the pyres would put the south pyre well past Bowie Street, which is more than just a little beyond St. Joseph Church.

In 1906, Pablo Diaz used St. Joseph Church as his point of reference when he told Barnes that the north pyre had been 200 yards east of the church. So, perhaps Barnes meant 250 yards from the church, not between the pyres. I measured from St. Joseph Church to where I believe the Springfield House had been to see where that would be today. This came to 243 yards (Figure #9). And that would be “just a little beyond St. Joseph Church.”

Both of these scenarios are purely my speculation. We may never know what Barnes actually meant, but it’s also interesting how close these scenarios are to where I’ve placed the two pyres.

Where the North and South Funeral Pyres of the Alamo Defenders Would Have Been On Today’s E. Commerce Street.

From Charles Barnes’s articles and the historic Sanborn maps of San Antonio, I’m confident that I’ve located where on E. Commerce Street the north and south funeral pyres of the Alamo defenders had been. Figure #9 Google satellite map shows those locations: 1. the north pyre, 2. the south pyre, and 3. the location of De Zavala’s tablet, which is “in the vicinity of the original location.”

WHAT BECAME OF THE REMAINS OF THE ALAMO DEFENDERS?

Witnesses told how the pyres had burned for over two days, consuming the bodies of the Alamo heroes. Only a few bone fragments remained among the ashes when the flames died out. The question is, what became of those bones and ashes? What happened to the defenders’ remains is as convoluted as any Alamo story. In the next few posts in my Searching for the Remains of the Alamo Defenders series, I’ll present the many accounts of what may or may not have become of those remains.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

The cover art is of the two burning funeral pyres by Gary S. Zaboly

Center for Archaeological Research. “Chapter 7: The Mystery of the Alamo Funeral Pyres: 185 Years of Searching for that Hallowed Ground.” An Archival and Archaeological Review of Reported Human Remains at Alamo Plaza and Mission San Antonio de Valero, San Antonio, Bexar County, Texas , The University of Texas at San Antonio, June 2022, colfa.utsa.edu/_documents/car/sr-000/sr-no-36.pdf, p. 131-180.

City of San Antonio, Texas. “HemisFair.” City of San Antonio Office of Historic Preservation, City of San Antonio, www.sanantonio.gov/historic/scoutsa/HistoricDistricts/HemisFair. Jan. 2024.

Fox, Anne A., and Marcie Renner, editors. “The Ludlow House and Moody Site.” Historical and Archaeological Investigations at the Site of Rivercenter Mall (Las Tiendas) San Antonio, Texas, edited by I. Waynne Cox et al., principal investigator by Robert J. Hard et al., Center for Archaeological Research The University of Texas at San Antonio, 1999, p. 80. Center for Archeological Research, Archeological Survey Report No. 270 , car.utsa.edu/CARResearch/Publications/ASRFiles/201-300/ASR%20No.%20270.pdf.

Hansen, Todd. “Builders’ Spades Turn Up Soil Baked by Alamo Funeral.” The Alamo Reader, A Study in History, First Edition, STACKPOLE BOOKS, 2003, p. 539.

Hansen, Todd. “Felix Nuñez Interview of 1889.” The Alamo Reader, A Study in History, First Edition, STACKPOLE BOOKS, 2003, p. 483.

Hansen, Todd. “Pablo Díaz 1906 interview. The Alamo Reader, A Study In History, First Edition, STACKPOLE BOOKS, 2003, p. 530.

Hansen, Todd. “Dr. Bernard, journal, 1836 and later? The Alamo Reader, A Study In History, First Edition, STACKPOLE BOOKS, 2003, p. 615.

“HemisFair ’68.” Wikipedia, Wikipedia, 24 July 2024, en.m.wikipenia.org/wiki/HemisFair_%2768.

Keckeisen, S. Katherine. “The Other Messengers .” City of Austin, Texas, http://www.austintexas.gov/sites/default/files/Parks/Dickinson/The_Other_Messenger_pdf. Oct. 2023.

Matovina, Timothy M. “Aged Citizen Describes Alamo Fight and Fire: Díaz Saw Terrible Carenag”e The Alamo Remembered, Tejano Accounts and Perspective, University of Texas Press, Austin, 1995, p. 75.

Matovina, Timothy M. “Aged Citizen Describes Alamo Fight and Fire,” “He Saw the Ashes of the Heroes” The Alamo Remembered, Tejano Accounts and Perspective, University of Texas Press, Austin, 1995, p. 76-77.

Matovina, Timothy M. “The Story of Don Pablo.” The Alamo Remembered, Tejano Accounts and Perspective, University of Texas Press, Austin, 1995, p. 104.

Matovina, Timothy M. “The Burning of the Bodies’ The Alamo Remembered, Tejano Accounts and Perspective, University of Texas Press, Austin, 1995, p. 105.

Reveley, Sarah. “Hallowed Ground: Site of Alamo Funeral Pyres Largely Lost to History .” San Antonio Report, San Antonio Report, 7 Jan. 2017, sanantonioreport.org/hallowed-ground-site-of-alamo-funeral-pyres=largely-lost-to-history/.

Ruiz, Francisco Antonio. “The Story of the Fall of the Alamo.” Sons of the Dewitt Colony, Sons of the Dewitt Colony, www,sonsofthedewittcolony.org/adp/archives/newsarch/ruizart.html. Feb. 2022. As it appeared in the San Antonio Light newspaper of Sunday March 6, 1907.

Texas Historical Markers. “Alamo Funeral Pyre.” Texas Historical Markers, Texas Historical Markers, texashistoricalmarkers.weebly.com/funeral-pyre.htm. Oct. 2023.

University of Texas at Austin Library. “Perry-Castaneda Library Map Collection.” Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps Texas (1877-1922), The University of Texas at Austin, mb.lib.utexas.edu/maps/sanborn/s.htm/#top. Oct. 2023.

University of Texas Libraries Special Collections. “M. Halff & Bro. Building, southwest corner of E. Commerce and Rusk Streets, San Antonio Texas, ca. 1941.” Digital Collections, The University of Texas at Austin , lib.utsa.edu/specialcollections/reproductions/copyright. June 2023.

Center for Archaeological Research. “Chapter 7: The Mystery of the Alamo Funeral Pyres: 185 Years of Searching for that Hallowed Ground.” An Archival and Archaeological Review of Reported Human Remains at Alamo Plaza and Mission San Antonio de Valero, San Antonio, Bexar County, Texas. The University of Texas at San Antonio, June 2022, colfa.utsa.edu/_documents/car/sr-000/sr-no-36.pdf, p. 131-180.

Fascinating subject; your entire series is well-written and thoroughly-researched.

LikeLike

Thank you so much

LikeLike

amazing research….thank you for your dedication and efforts. Sad to know that a place 1000s of people walk aimlessly over everyday is the resting spot of these great heroes remains.

LikeLike

Thank you so much Lance. This series has been in the works for decades. There are so many myths about the Alamo I wanted my information to be as correct as possible. You’re going to love the next chapter

LikeLike

excited for the next posts!!!

LikeLike

So sad. The city fathers back then could’ve placed eminent domain on those two spots and turned them into two small parks with benches and some type of memorial remembering the defenders. People could’ve sat and contemplated what happened on that site. I suppose something like that could still happen in the distant future. I hope so. When is your next call concerning what happened to the ashes coming out? I’m looking forward to it.

LikeLike

So true Walter. This neglect to the heroes remains is sadly an undercurrent in my posts. However, I have an idea. The Alamo Historical Society is a very influential organization. There’s no reason that they can’t fund markers at the site. Or as you suggested. A quiet place to sit and remember. I received a message from a descendant of David Crockett, who appreciated my pyre site posts, which gave her a place to honor her ancestor. It would nice to have a place for her to sit, rather than standing on the sidewalk.

I in the final polishing ofpart five, the funeral. Thanks so much for your comment.

LikeLike

I

LikeLike