“I turned onto the Alameda at the present intersection of Commerce and Alamo Streets. Looking eastward I saw a huge crowd gathered. Intuitively I went to the place. It was just beyond where the Ludlow now stands. The crowd was gathered around the smoldering embers and ashes of the fire that I had seen from the mission. It was here that the Alcalde (Ruiz ) had ordered the bodies of Bowie, of Crockett, Travis and all of their dauntless comrades who had been slain in the Alamo’s unequal combat to be brought and burned. I did not need to make inquiry. The story was told by the silent witnesses before me. Fragments of flesh, bone, and charred wood and ashes revealed it in all its terrible truth.”

Pablo Díaz, to Reporter and Historian Charles M. Barnes, in a July 1, 1906 Interview for the San Antonio Express Newspaper.

This was how the 90-year-old Pablo Díaz, an eyewitness to the fall of the Alamo, had described what he’d seen at the site of the north pyre in 1836 to Charles Barnes in 1906. But what’s most important in our search is that Díaz provided a hint to the location of the north pyre when he said, “It was just beyond where the Ludlow now stands.”

Not only Díaz but other eyewitnesses used the Ludlow House as their point of reference for the location of the north pyre. But it would be a building erected later, “just beyond the Ludlow,” the Moody Building, that would play a more pivotal role in our quest for the site of the north pyre.

As it was with the Alameda, all traces of either of these buildings have long been destroyed by continued commercial development. However, I was able to piece together enough information to calculate a fair location for the north funeral pyre by using witness accounts, the San Antonio Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, and city records. But most of all, in our journey of discovery, the 1984 University of Texas’s Rivercenter Mall Archaeological Study was the most substantial.

To begin with, we’ll examine the area’s history on E. Commerce Street, where the north pyre is believed to have been.

The History of the North Pyre Site

Early land records show that the land on the north side of the Alameda, east of the Pueblo de Valero, which locals recognized as the location of the north funeral pyre, remained primarily vacant and undeveloped in the decades following the cremation of the bodies of the Alamo defenders.

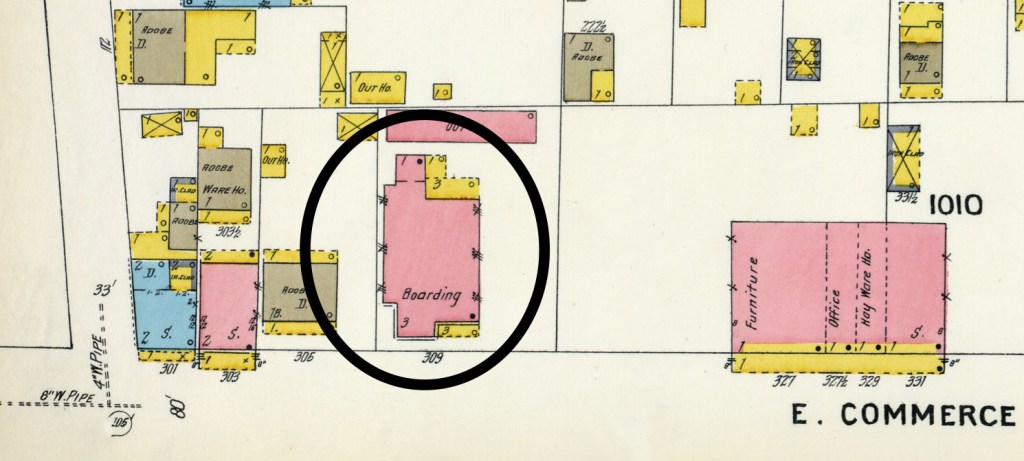

This changed in 1903 when Daniel Ludlow purchased two lots on the western portion of that area and built a three-story brick boarding house known as the Ludlow House. I’ve circled the Ludlow House on Sheet #107, Volume 2, of the 1904 Sanborn map (Figure #1).

Although the Ludlow House was used by Pablo Díaz and other eyewitnesses as their point of reference for the location of the north pyre, records show that only a tiny portion of the pyre’s western edge had been on the Ludlow property.

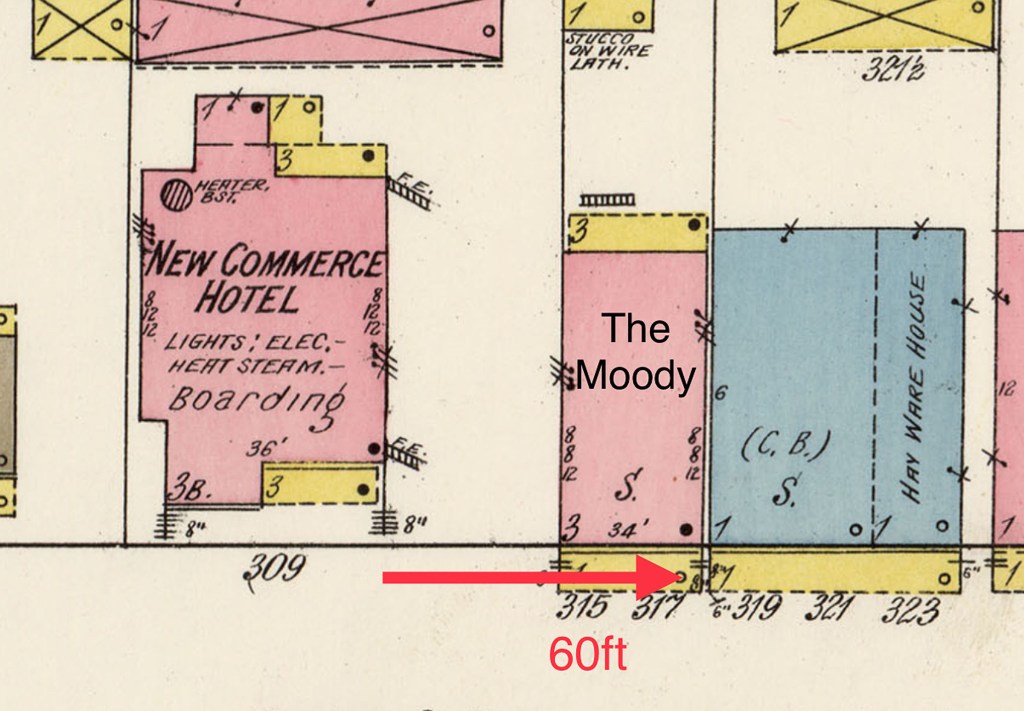

The actual location of the north pyre was told by reporter and historian Charles Barnes in his 1911 San Antonio Express newspaper article, Builders Spades Turn Up Soil Baked By Alamo Funeral Pyres. In his article, Barnes says the north pyre was “…on the north side of East Commerce Street, adjoining the Ludlow House.” Barnes went on to say, “The pyre occupied a space about ten feet in width by sixty in length and extended from northwest to southeast from the property owned by Mrs. Ed Steves, on which the Ludlow House is built..” Barnes’s description of the location of the north pyre agrees with Pablo Díaz, who said it was “just beyond where the Ludlow now stands.” However, the purpose of his article wasn’t to just describe the location of the north pyre but to tell how fragile this small and historically essential piece of Alamo history would soon be lost to development. And it began with the Moody Building.

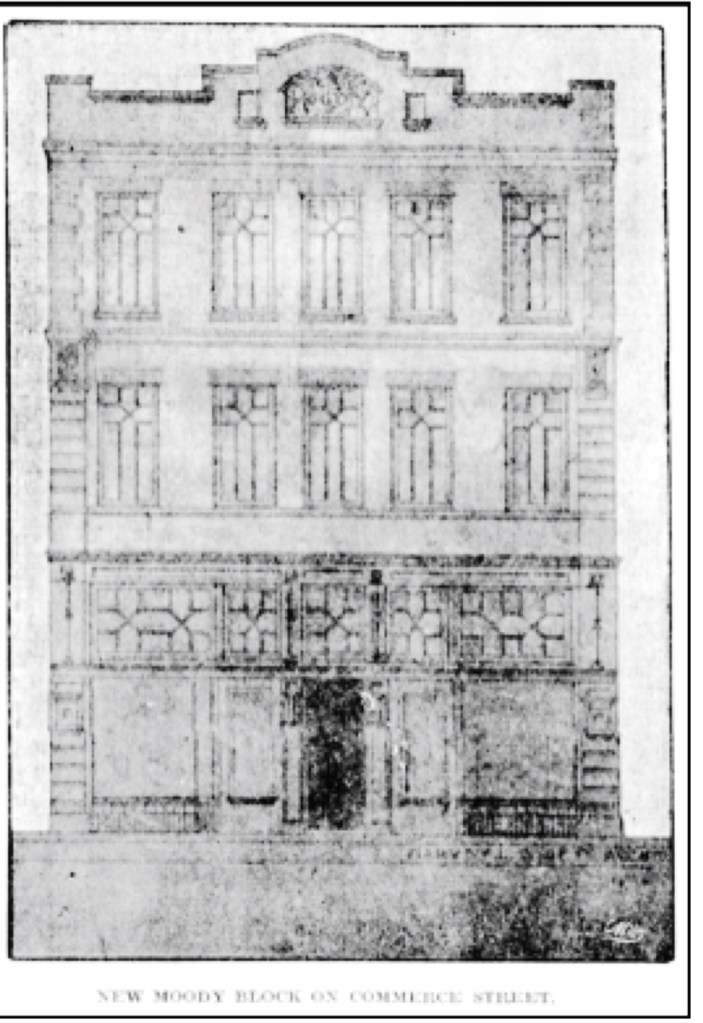

In 1910, Dr. George H. Moody began the construction of a three-story apartment building two lots east of the Ludlow. Barnes quickly noted that this building would have a devastating effect on the north funeral pyre’s site. So much so that he opened his 1911 article with, “Where workmen are excavating for the cellar of a new building that will stand on the spot of one of the two funeral pyres…” As Barnes explained in his article, the north pyre had gone up “to and through the property that the Moody structure is to occupy…” and that “the spot where the cellar is being dug comprises one-half of the area on which the first pyre mentioned (the north pyre) was located.”

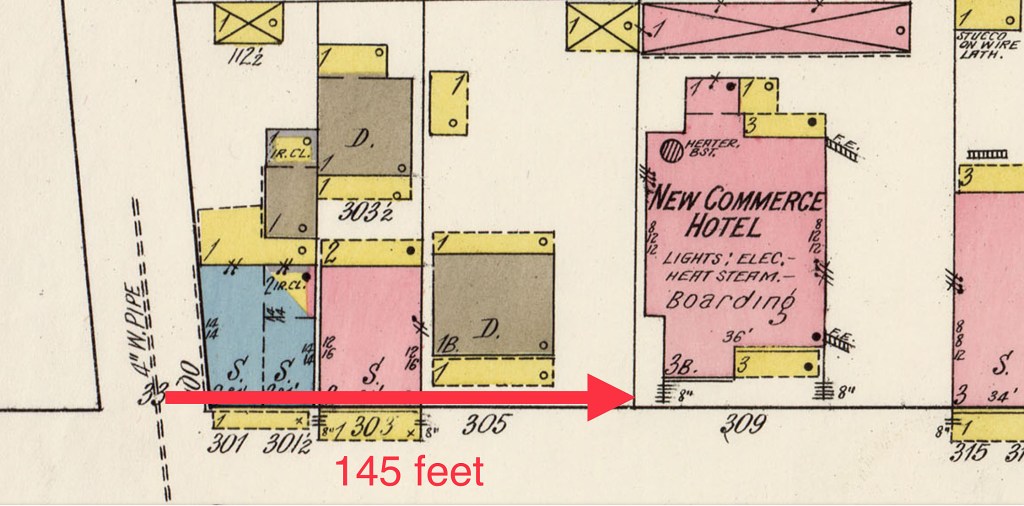

To visualize the impact the Moody Building had on the north pyre’s site, I used Sheet #122, Volume 2, of the 1912 San Antonio Sanborn Map. This map shows both the Ludlow, now the New Commerce Hotel, and the Moody Building. I’ve marked the sixty feet east of the Ludlow that Barnes said was the length of the north pyre. This shows that the Moody Building had taken up the eastern half of where the pyre had been (Figure #2).

It’s unknown if David Ludlow or Dr. Moody knew or cared about the historical significance of the land on which their two buildings stood. But neither one had erected a monument or a marker telling what had happened there. Again fulfilling another of Barnes’s predictions, “… whereon the bodies of those slain in the Alamo’s defense were consumed, is one of the memorable places of San Antonio, never marked and constantly passed unheeded. Few know that such a prominent event in history was there enacted.” And so it would remain for another eight years before that ground where the Alamo defenders’ bodies had been cremated would finally receive its formal recognition.

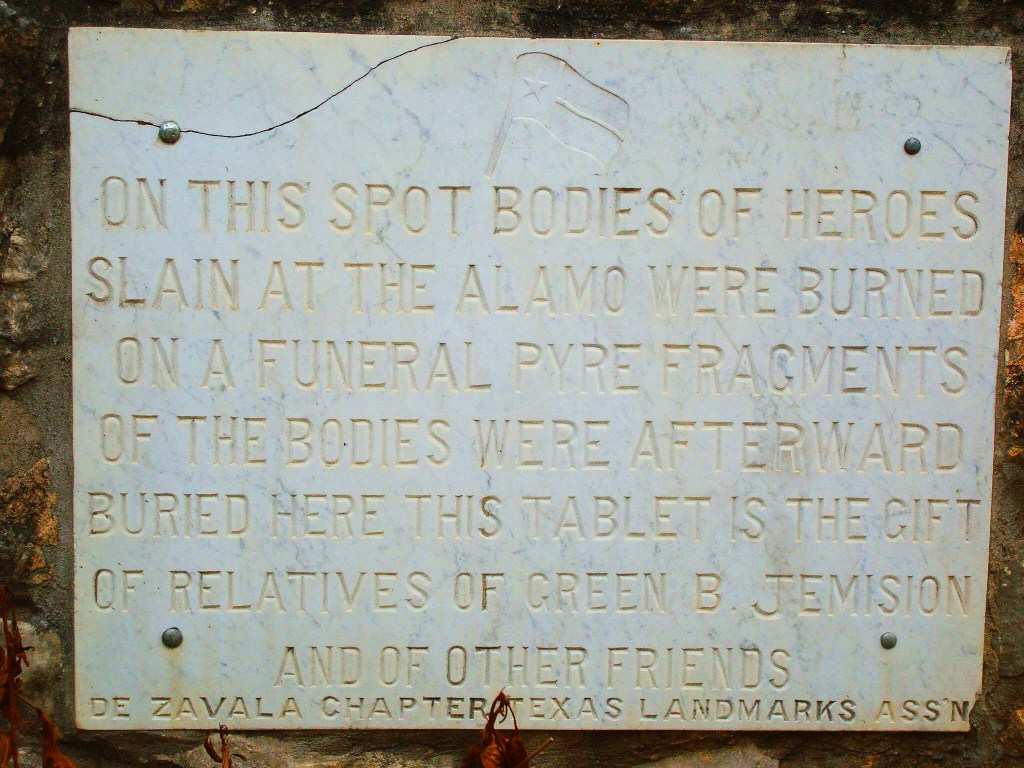

On March 6, 1918, eighty-two years after the fall of the Alamo, Adina De Zavala, one of the saviors of the Alamo, and her De Zavala Chapter of the Texas Landmark Association, led a grand celebration as she unveiled two marble tablets that identified the sites of the two funeral pyres. These markers had been mounted onto the buildings that sat on those two sites. The marker for the north pyre was installed on the Geneva Apartment building, formerly the Moody. However, this remembrance would be short-lived as commercial development again took over.

The first of the north pyre buildings to fall was the Ludlow. Around 1957, this long-abandoned building was demolished for a parking lot. Later, the Joske Department Store would build its Tire Center there.

Although mainly used as an apartment building, the Moody became home to the Salvation Army around 1939. There’s said to be a photo that shows De Zavala’s tablet still mounted on that building. But the Moody, with its historical marker, would also fall to the wrecking ball.

In 1961, the properties of the Moody, Ludlow, and the vacant lot between them were combined to construct a Sears Auto Center. This effectively eliminated any trace of the funeral pyre’s remains. This became apparent in the 1984 Rivercenter Mall archaeological study, which I’ll cover later. In addition, sadly, De Zavala’s marker also disappeared during the Moody’s demolition.

However, the most substantial redevelopment of the north pyre site came in 1984, with the construction of the Rivercenter Mall complex. The complex would include the Marriott Rivercenter Hotel, the largest hotel in the city at the time; a 185,000-square-foot enclosed shopping mall; 300,000 square feet of office space; and a 1,400-square-foot parking garage. In addition, the Riverwalk was extended under E. Commerce Street and into a Lagoon they’d created between the mall and hotel.

Those properties, on which the north pyre had been, were wholly absorbed into the Rivercenter complex, bringing another of Barnes’s predictions to fruition when he wrote, “It will not be long before this spot, and the one where the other funeral pyre was built will be the sites of buildings for commercial purposes, and the populace, in all probability, will forget that either place was ever of such historical interest.”

Now, knowing the site’s history, it’s time to discover where on E. Commerce Street the north pyre might have been.

Locating the North Pyre

My hunt to find the site of the Alamo defenders’ north funeral pyre has been challenging. This is mainly because the Ludlow House and the Moody Building, the most often-used landmarks to describe the pyre’s location, are gone without a trace. Without knowing where these two buildings were located, identifying the site of the north funeral pyre would be nearly impossible. So, my first task was to find where the Ludlow and the Moody had been on E. Commerce Street.

To accomplish this, I needed a source that featured the Ludlow and Moody buildings and a point of reference that still exists today. I found those on the maps of Sheets #122 and #117 of Volume 2 of the 1912 Sanborn Fire Insurance maps of San Antonio.

Sheet #122, which I used earlier in this post, has the Ludlow House (then the New Commerce Hotel) and the Moody Building. Sheet #117 has the needed reference point that remains today: St. Joseph Catholic Church. Using these two maps, I should be able to locate where the Ludlow and Moody buildings would have been on E. Commerce.

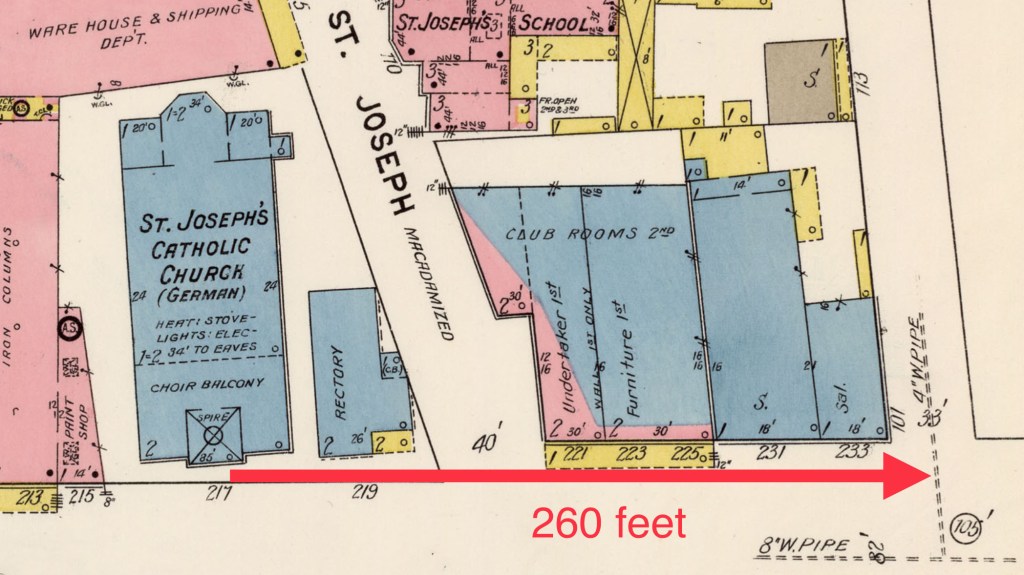

I began with Sheet #117. Measuring east from St. Joseph Church to the center of the now-gone Bonham Street, I calculated that distance to be 260 feet (Figure #3). Then, with Sheet #122, I went west from the Ludlow back to Bonham Street. That came to roughly 145 Feet (Figure #4). Adding these two figures together would have made the distance from St. Joseph Church to the Ludlow at around 405 feet. However, to find the north pyre’s site, I needed to be more specific about the locations of those two buildings. To do this, I needed to know the dimensions of the Ludlow and Moody. Most importantly, I needed to know their frontage along E. Commerce Street. To achieve this, I went back to the map of Sheet #122.

Using the diagrams of the Ludlow and Moody buildings shown on the Sanborn map, I calculated the Ludlow as having a depth of about 90 feet and an E. Commerce Street frontage of 60 feet. The Moody Building was slightly smaller, with a depth of 70 feet and a frontage of 30 feet. However, one other measurement was crucial to finding the north pyre: the frontage of the vacant lot that sat between the Ludlow and the Moody. This came to around 40 feet. With this information, I was ready to identify the probable locations of the Ludlow and Moody buildings on today’s E. Commerce Street.

Starting at the 405-foot mark from St. Joseph Church, I placed my diagram representing the dimensions of the Ludlow. This showed that the Ludlow/New Commerce Hotel was located east of the entrance to the Rivercenter parking garage and where the Yard House restaurant is today. Next to the Ludlow diagram I added the 40 feet for the vacant lot. Next to this, I placed my diagram of the Moody Building. This puts the location of the Moody Building where the Riverwalk extension goes under E. Commerce Street (Figure #5). Now, knowing the locations of the Ludlow and Moody buildings, it was time to pinpoint where the Alamo defender’s north funeral pyre would have been.

As I wrote earlier, in 1912, Charles Barnes described the north pyre as having been 10 feet wide and 60 feet long. He also said the pyre had run east from the Ludlow, across the vacant lot, and into the Moody Building. Following this description, I created a diagram with the pyre’s dimensions and placed it on the Google map next to the diagram of the Ludlow. This puts the location of the north funeral pyre as having been at the Margaritaville entrance to the mall and out into the west side of the Riverwalk extension (Figure #6). But are my calculations accurate? There is an eyewitness account that helps to confirm my findings.

Pablo Díaz described to Barnes the location of the north pyre this way, “… the main funeral pyre was about two hundred yards east of where St. Joseph’s Church now stands and just beyond this big red brick house (meaning the Ludlow) ….” Using Díaz’s account, I again used the Google map, measuring 200 yards (600 feet) east from St. Joseph Church. This also came to where the Riverwalk extension goes under E. Commerce Street. I’ve marked this spot on the map with a star (Figure #7).

The Alameda of 1836 was narrower than the E. Commerce Street of today. With that, the actual ground on which the Alamo defender’s ashes had laid could be out into the street or further into the mall. But for pilgrims visiting this hollowed area, you’ll be at, or very close to, the spot of the north pyre if you stand on the north side of E. Commerce Street by Margaritaville and the western entrance to the Riverwalk.

The University of Texas’s 1984 Rivercenter Mall Archaeological Study

In 1984, before construction on the massive Rivercenter Mall complex began, the City of San Antonio partnered with the Texas State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO) to hire the Center for Archaeological Research (CAR) of the University of Texas San Antonio to conduct an in-depth archaeological study of the mall’s site before it was covered over and lost forever.

The area of study was significant. It encompassed the land south of the Menger Hotel, enclosed by Alamo Plaza Street on the west, Bowie Street on the east, and E. Commerce Street on the south.

Although this archaeological dig promised to reveal much about that area’s past, a small section of land on the north side of E. Commerce Street was of the most interest. This small section was believed to have been the location of the Alamo defenders’ north cremation pyre.

This would be the first time an archaeological investigation had been undertaken at the proposed site of the north pyre. Knowing the sensitive and, in some ways, controversial nature of the north funeral pyre site, the archaeologists took the utmost care and precautions in their investigation.

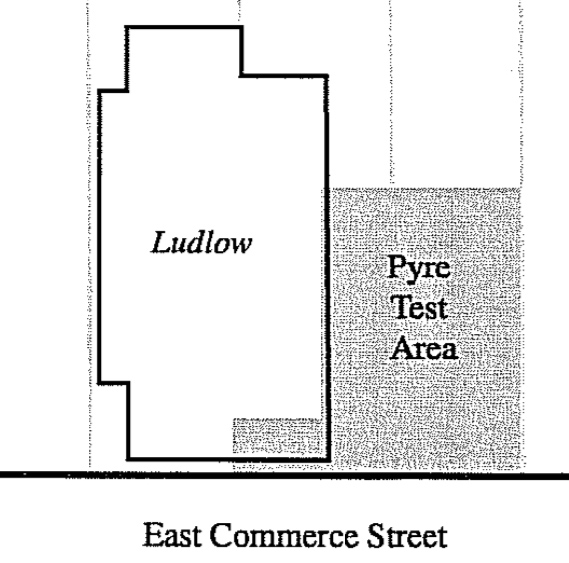

Aware of the site’s development and redevelopment history over the one hundred forty-eight years since the Battle of the Alamo, the archaeological team focused their efforts on the area that had been the vacant lot between the Ludlow and Moody buildings. They believed this area may have seen the least developmental disturbance, offering the best chance of finding remnants of the north funeral pyre. The shaded area on the diagram (Figure # 8) indicates where the archeologists had excavated.

After their extensive investigation, the archaeologists reported that they had found no trace of human bones, ash, or burnt wood at the site. Their conclusion was that if this was indeed the location of the Alamo defender’s north funeral pyre, then the significant development of the site, including the digging of basements for the Ludlow and Moody buildings, had eliminated all traces of the pyre that may have existed. They also stated that due to the lack of evidence, this may not have been one of the sites of a pyre.

This is detailed in the University of Texas’s 1984 Rivercenter Mall Archaeological Study, Chapter 12: The Ludlow House and Moody Building, and Chapter 15: Searching for the Funeral Pyre. Here’s the link to the studies report: scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita/vol1999/iss1/3/.

In Part 4 of this series, I’ll use the same methodology to locate the south funeral pyre.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

The cover art of the burning funeral pyre is by Gary S. Zaboly

Fox, Anne A., and Marcie Renner, editors. “The Ludlow House and Moody Site.” Historical and Archaeological Investigations at the Site of Rivercenter Mall (Las Tiendas) San Antonio, Texas, edited by I. Waynne Cox et al., principal investigator by Robert J. Hard et al., Center for Archaeological Research The University of Texas at San Antonio, 1999, p. 80. Center for Archeological Research, Archeological Survey Report No. 270 , car.utsa.edu/CARResearch/Publications/ASRFiles/201-300/ASR%20No.%20270.pdf.

Hansen, Todd. “Builders’ Spades Turn Up Soil Baked by Alamo Funeral.” The Alamo Reader, A Study in History, First Edition, STACKPOLE BOOKS, 2003, p. 539.

Hansen, Todd. “Pablo Díaz 1906 interview. The Alamo Reader, A Study In History, First Edition, STACKPOLE BOOKS, 2003, p. 530.

Hansen, Todd. “Dr. Bernard, journal, 1836 and later? The Alamo Reader, A Study In History, First Edition, STACKPOLE BOOKS, 2003, p. 615.

Huffines, Alan C. . “Phase VI: The Aftermath.” Blood of Noble Men. The Alamo, Siege & Battle, illustrated by Gary S. Zaboly, first Addition, Eakin Press, 1999, p. 190.

Matovina, Timothy M. “Fall of the Alamo, The Massacre of Travis and His Brave Associates, Francisco Ruiz 1860 account” The Alamo Remembered, Tejano Accounts and Perspective, University of Texas Press, Austin, 1995, p 44.

Matovina, Timothy M. “Aged Citizen Describes Alamo Fight and Fire: Díaz Saw Terrible Carenag”e The Alamo Remembered, Tejano Accounts and Perspective, University of Texas Press, Austin, 1995, p. 75.

Matovina, Timothy M. “Aged Citizen Describes Alamo Fight and Fire,” “He Saw the Ashes of the Heroes” The Alamo Remembered, Tejano Accounts and Perspective, University of Texas Press, Austin, 1995, p. 76.

Matovina, Timothy M. “Aged Citizen Describes Alamo Fight and Fire,” “He Saw the Ashes of the Heroes” The Alamo Remembered, Tejano Accounts and Perspective, University of Texas Press, Austin, 1995, p. 76-77.

Matovina, Timothy M. “The Story of Don Pablo.” The Alamo Remembered, Tejano Accounts and Perspective, University of Texas Press, Austin, 1995, p. 104.

Reveley, Sarah. “Hallowed Ground: Site of Alamo Funeral Pyres Largely Lost to History .” San Antonio Report, San Antonio Report, 7 Jan. 2017, sanantonioreport.org/hallowed-ground-site-of-alamo-funeral-pyres=largely-lost-to-history/.

Ruiz, Francisco Antonio. “The Story of the Fall of the Alamo.” Sons of the Dewitt Colony, Sons of the Dewitt Colony, www,sonsofthedewittcolony.org/adp/archives/newsarch/ruizart.html. Feb. 2022. As it appeared in the San Antonio Light newspaper of Sunday March 6, 1907.

Thank you for your wonderful and very thorough work. I’m a member of Alamo Defenders Descendants Association. In fact, I’m a descendant of Green B. Jameson, so it is my relatives who are mentioned on Adina de Zavala’s marble plaque. The 1995 metal plaque says the marble plaque was place on the Halff Building at the corner of Commerce and Rusk. Where on the Sanborn maps was the Halff Building located?

LikeLike

Thank you so very much Tom for your kind words. And coming from a descendant makes them even more special. There was so much to present on the north pyre that including the south pyre would have made it way too long. My next post will be on the north pyre. And again, thank you so much.

LikeLike

Tom, to answer your question about the Halff building, send me an email at rdcurrent@gmail.com and I send you a preview of my part 4.

LikeLike