“It was but a small affair.”

GENERAL SANTA ANNA SHORTLY AFTER OF BATTLE.

This “small affair” of Santa Anna and his massacre at Goliad would motivate the people of Texas to defeat him at San Jacinto on April 21, 1836. The battle cry of the Texians at San Jacinto was “Remember the Alamo, Remember Goliad.” And more impactful, this “small affair” would lead to Mexico losing Texas. And yet this thirteen-day siege and ninety-minute battle continues to be wrapped in mystery, legend, and myth. Some of these legends and myths developed due to the lack of eyewitnesses inside the Alamo during the siege and final battle.

The only ones to survive in the Alamo were Travis’s slave Joe, Susanna Dickinson, and a small group of Tejano women and children. Of these, only Joe was on the north wall at the very start of the attack. But after Travis was killed, he ran back to their room on the west wall, spending the rest of the battle in hiding. Susanna Dickinson and the other women and children were in the church’s dark Sacristy, only hearing the horrible sounds of the battle coming from outside. None actually witnessed the battle itself.

With the lack of eyewitness accounts from inside the Alamo, much of what we know of what occurred during the siege and battle comes from the journals of Mexican officers. However, even some of these accounts have issues with their accuracy. The Journal of General Vicento Filisola is considered one of the most reliable. But Filisola wasn’t in Béxar during the siege and attack. He didn’t arrive until March 8, two days after the final battle. So, It’s accepted that most of what he wrote came from secondhand sources.

With some of the other officers, their accounts may have been clouded because of their less than favorable opinions of Santa Anna, like his secretary Romón Martínez Caro and Lieutenant José Enrique de la Peña. With these factors in mind, I will explore the most asked question about the battle of the Alamo: how many defenders and Mexican soldiers participated and how many casualties were suffered. I’ll start with the Alamo defenders and begin with Amelia Williams’s list.

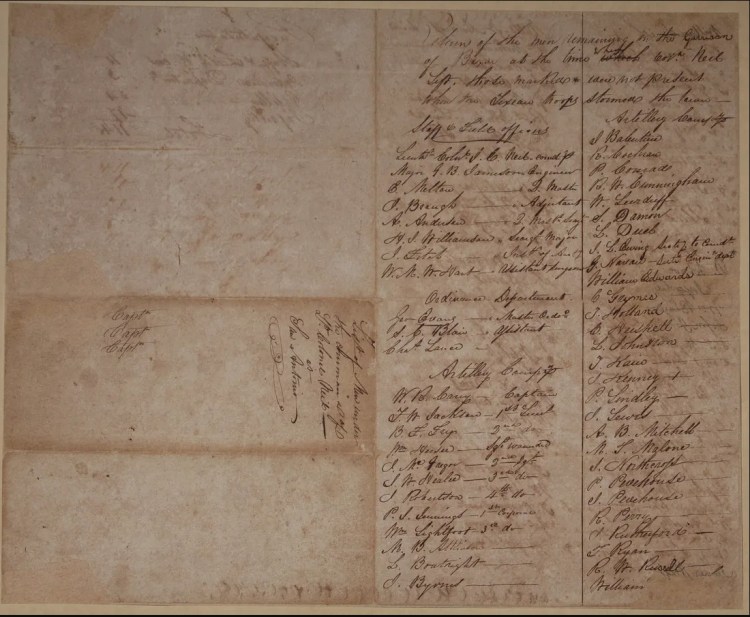

In the 1930s, historian Amelia Williams conducted an extensive study to identify the Alamo’s defenders. Through her research, she compiled a list of 187 names. For decades, this list defined who the defenders were, and these names are engraved on the Alamo Cenotaph. But is Williams’s list complete? Even Williams believed there could have been more defenders when she stated that twelve other possible names could have been included. Since her list was first published, other historians have raised the number of defenders to 189. In 1990, John M. Hayes of Tennessee was added. So why is there such uncertainty in the number of defenders? It goes back to the sources she had to work with.

When Williams did her research, what was available to her were just thousands of letters, interviews, and land grants. Using only these, she pieced together those she believed had fallen at the Alamo. What she didn’t have, which would have made her job easier, was the military’s most basic record: a muster roll. But alas, as it was without having eyewitnesses, the Alamo also lacked a muster roll of those in the garrison. Well, that’s not entirely correct.

Lieutenant Colonel James Clinton Neill, who commanded the Alamo garrison before Travis and Bowie, had compiled a muster roll of the garrison shortly after he took command in January of 1836. Neill’s muster roll listed 110 men under his command. However, his roll doesn’t contain the names of those who came later with Travis, Bowie, Crockett, and Philip Dimmitt. In addition, Neill’s roll also doesn’t consider the men who left after their enlistment had ended or left to serve elsewhere in Texas. What’s also interesting is that most of those at the Alamo when the siege began had just recently arrived in Texas.

So, what was the size of the Alamo garrison when the siege began? No muster roll of either Travis or Bowie has yet to be discovered. So, without one, all we have to go on are letters and reports.

In one of his first letters at the start of the siege, William Travis wrote, “We have 150 men & are determined to defend the Alamo to the last.” Launcelot Smithers, the courier who most likely carried that letter, confirmed what Travis said when he later wrote, “When I left [the Alamo] there were 150 determined to do or die.” Another source was Santa Anna’s personal secretary, Romón Martínez Caro, who stated in his report of 1837, “According to the citizens of the place [Béxar], the enemy, which numbered 156, took refuge in the so-called fortress of the Alamo.” So, it’s safe to assume that at the start of the siege, the garrison numbered around 150 men. Now for the trickier question: how many defenders fought and died in the final attack on March 6?

The lack of documentation in the Alamo saga has always been a challenge for historians, especially regarding what occurred inside the fort during the twelve-day siege. During those twelve days, Travis was very prolific in his writings seeking help, which caused couriers to come and go from the Alamo, changing the number of defenders in the fort almost daily.

After mentioning the 150 men in his letter of February 23, Travis fails to give any further indication of the number of men under his command in his letters. He only writes of being reinforced by the “Immortal 32” on March 1 and James Bonham on March 3. Travis also neglects to mention those men who had left the Alamo. We know from personal accounts that twelve couriers, including Launcelot Smithers, had ridden out of the Alamo carrying Travis’s letters and didn’t return. And if you believe the legend, one other defender may have left the fort the night before the attack, Louis or Moses Rose, who didn’t cross Travis’s line.

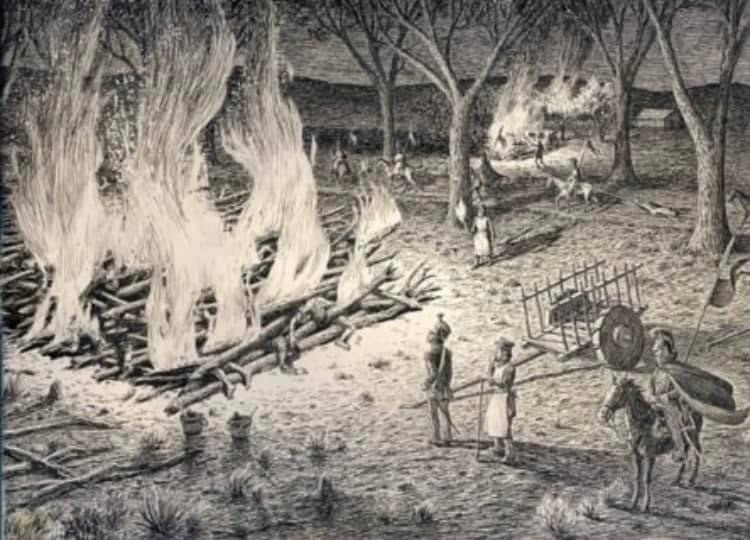

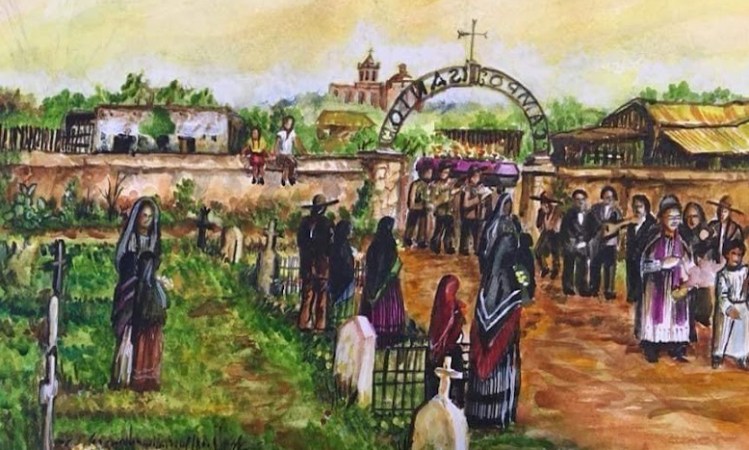

So far, no records from inside the Alamo have been discovered telling the number of defenders at the time of the attack. Again, we’ll seek answers from sources outside the Alamo’s walls. One of the first to give a written report on the number of defender casualties was Romón Martínez Caro. Again, in his 1837 report, Caro wrote, “The enemy died to a man, and its loss may be said to have been 183 men, the sum total of their force.” We also have the later interview statements by Mexican soldier Felix Nuñez and the Mayor of Béxar, Francisco Antonio Ruiz. These men claim to have taken part in stacking the defender’s bodies on the two cremation pyres after the battle. Nuñez reported that he had counted 180 bodies, while Ruiz said his count was 182. Since both Nuñez and Ruiz’s figures come from the bodies on the pyres, we know of one defender who wasn’t included in their count, Jose Gregorio Esparza. Esparza’s family was given permission to bury him in San Fernando Church’s Campo Santo (cemetery).

Another account comes from Lieutenant José Enrique de la Peña. De la Peña wrote in his memoir With Santa Anna in Texas years after the battle, “According to documents found among these men and to subsequent information, the force within the Alamo consisted of 182 men.” This figure goes along with those of Caro, Nuñez, and Ruiz. But then de la Peña adds, “But according to the number counted by us, it was 253.” In his book Blood of Noble Men, author Alan C. Huffines quotes an unidentified Mexican soldier who said there were “257 corpses.” The last and most fascinating, concerning the number of Alamo dead, comes from General Filisola. Filisola wrote, “Of the enemy dead there were 150 volunteers, 32 people of the Town of Gonzáles…and some twenty people and tradesmen of the city of Béxar itself.” This totals a figure of 202 defenders. But again, not being in town, Filisola most likely just pieced together what he heard.

Why such a discrepancy in the numbers? Again, the biggest reason is the lack of documentation. But also, some historians think there may have been more than the two cremation pyres or that Mexican soldiers had hastily buried some defenders’ on the Alamo’s grounds against Santa Anna’s orders, which would have thrown off the body count. It’s just another Alamo mystery.

Finding the number of Mexican soldiers who took part in the siege and final battle is a little easier than with the defenders, thanks to the journals and memoirs of Santa Anna’s officers. However, even these are not one hundred percent trustworthy.

According to Santa Anna and General Filisola’s accounts, the Army of Operations had 6,000 to 8,000 soldiers at the start of the Texas campaign. From these, General José de Urrea would take 500 to 600 men to march up the Texas east coast.

On February 16, 1836, the army’s main body crossed the Rio Grande River into Texas. Leading the Vanguard Brigade, 1st Division, were Santa Anna and General Remírez y Sesma. This forward brigade would consist of around 1,541 men.

Since the Vanguard Brigade was mainly comprised of cavalry, it moved quickly north, arriving in Béxar on February 23 and beginning the siege. However, as I wrote in Chapter I: The Road to the Alamo, the rest of the army suffered greatly from the harsh weather and poor trails. These conditions slowed the columns, stringing out the divisions for hundreds of miles. The last division General Filisola commanded wouldn’t reach Béxar until March 8.

The only significant Mexican reinforcement to arrive throughout the siege was General Gaona, who reached Béxar on the afternoon of March 3. With Gaona’s Brigade, the number of Mexican troops surrounding the Alamo at the time of the attack is estimated to be 2,370. But how many of those actually participated in the pre-dawn assault on the Alamo? Most Mexican sources, including Santa Anna, put the number of Mexican infantry attacking the Alamo at 1,400. Since this number is stated as infantry, it most likely doesn’t include Sesma’s Dolores Cavalry, stationed southeast of the fort on the Alameda. Sesma’s cavalry only intercepted the fleeing defenders. So, what were the casualties suffered by the Mexicans in the attack?

As with the number of defenders killed, the number of Mexicans killed and wounded varies between the Mexican and Texian reporting. However, some accounts do come to similar conclusions. Romón Martínez Caro wrote that 300 of Santa Anna’s soldiers were killed outright, with another 100 dying from their wounds. This goes along with Mexican soldier Manual Loranca’s statement that he took part in burying 400 of his fellow soldiers in the Campo Santo of San Fernando Parish. We also have the account from Dr. John (or Joseph) Bernard.

Dr. Bernard had been captured at Goliad and sent to San Antonio to help care for those Mexicans wounded in the attack. Dr. Bernard wrote in his journal on April 21, 1836, “The surgeon tells us that there were five hundred brought into the hospital the morning they stormed the Alamo, but I should think from appearances there must have been more. I see many around the town who were crippled; apparently, two or three hundred, and the citizens tell me that three or four hundred have died of their wounds.” So, from most sources, the number of Mexican soldiers killed and wounded seems to have been around 600.

To Summarize, in the pre-dawn of Sunday, March 6, 1836, around 1400, Santa Anna’s soldiers ran into heavier-than-expected resistance from the 180 to 200 men defending the Alamo. When the sun rose above the smoldering fort, it revealed that all the defenders had been killed, and 600 Mexican soldiers were either killed, dying, or badly wounded.

Some Alamo enthusiasts would like the number of Mexican soldiers killed to be higher. But let’s put this into perspective: those 600 Mexican casualties constituted nearly half of Santa Anna’s total attacking force. This is why Mexican Colonel Juan Nepomuceno Almonte said after the battle, “Another victory like this will destroy us.”

I enjoyed that story . Thank you

LikeLike