Sunday, March 6, 1836: There’s Victory in Death

Update on February 20, 2025

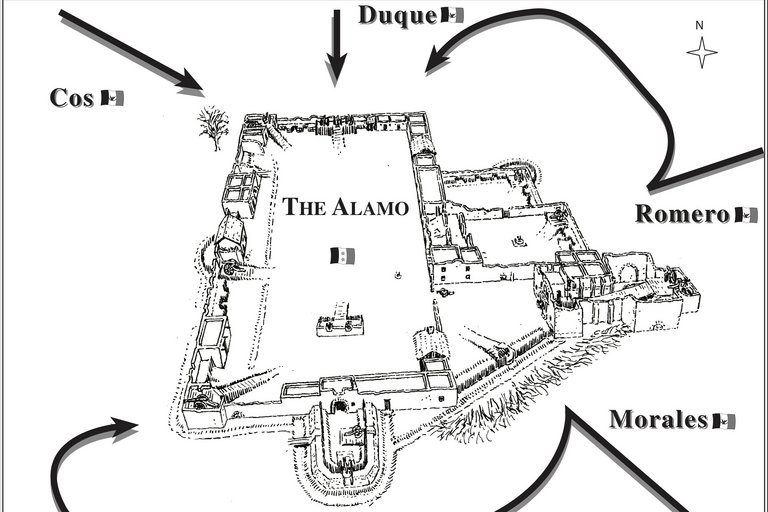

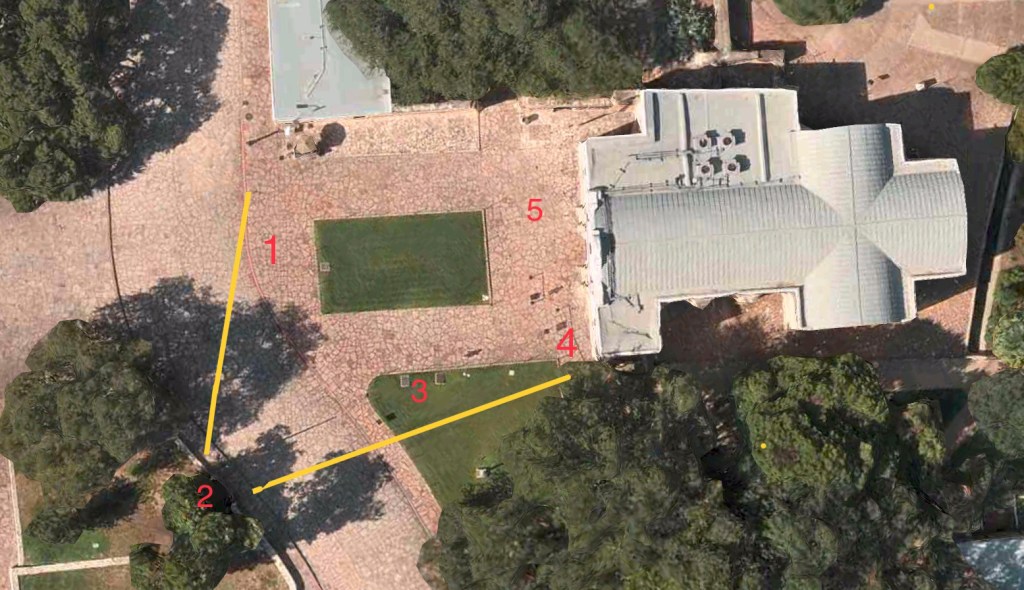

A little after midnight, Santa Anna moved his attacking forces into their positions around the Alamo. He had divided his troops into four columns: General Cos would attack from the northwest; Colonel Duque’s command would strike the center of the north wall; Colonel Romero’s columns would hit the walled courtyards on the east side of the fort, and Colonel Morales would assault the wooden palisade and Low Barrack main gate on the Alamo’s southside.

Near his northern command post, Santa Anna stationed four hundred of his most experienced soldiers in reserve. And southeast of the Alamo, he placed General Sesma’s Dolores Cavalry on the Alameda. From there, the cavalry could intercept any defender trying to escape or deserting Mexican soldiers.

As the time for the attack grew closer, Santa Anna’s sent forward scouts to dispatch the defender’s early warning pickets outside the walls. All was set; all that was needed was a little more daylight.

In that early morning, the interior of the Alamo was bathed in the blackness of the Texas night. Travis was asleep in his quarters on the west wall; Bowie lay sick and bedridden in his room in the Low Barracks; Crockett was at his post at the wooden palisade; and in the church’s sacristy, near their gun platform, Almaron Dickinson and José Gregorio Esparza slept with their families. The other defenders also lay in a deep sleep at their posts. Outside the walls, the Mexican soldiers lay on the cold, damp ground, waiting for the bugle calls sending them to their likely deaths. All was deathly quiet.

Just before 5:00 A.M., a nervous and cold Mexican soldier couldn’t contain himself; jumping to his feet, he cried out,” Viva Santa Anna! Viva Mexico!” The other soldiers picked up his cry. With his hope of a surprise attack dashed Santa Anna signaled the buglers to sound the charge.

On the Alamo’s north wall, the officer of the day, Captain John J. Baugh, heard the shouts from out of the darkness, followed by the bugle calls. Capt. Baugh didn’t need to guess what was taking place. Calling out at the top of his lungs, “The Mexicans are coming! The Mexicans are coming!” Shocked out of their sleep, the garrison leaped into action.

When the men of the Alamo reached the walls, they heard the sounds of stampeding feet before seeing the Mexican soldiers coming out of the pre-dawn gloom. Quickly, the roar of the Alamo’s cannons answered the Mexican attack. Instead of cannonballs, the gunners loaded their guns with grapeshot made from cut-up horseshoes, nails, and stones. This killing mixture ripped into the advancing Mexican columns. One of the first Mexican officers to fall was Colonel Francisco Duque. General Fernández Castrillón quickly took up his command.

On the north wall cannon platform, Travis encouraged his men with, “Come on boys! The Mexicans are upon us, and we’ll give them Hell!” Turning to the Tejanos, he called out in Spanish, “No rendirse muchachos” (Do not surrender boys).

At first, the heavy barrage from the Alamo’s cannons and rifles held off the advancing soldiers. At least twice, Santa Anna’s assault faltered. On the south side of the Alamo, Crocket and the other defenders were able to drive Colonel Morales’s men back to the Pueblo de Valero. General Cos and General Castrillón’s troops were staggered at the north wall by the cannons on the northwest corner and north wall platforms. On the east, Colonel Romero’s attack didn’t fare much better. The Cannons at the back of the Alamo church drove his men to the northwest. But the defender’s successes would be short-lived.

With their forward advancement halted by the Alamo’s gunfire, Cos’s men drifted to the east, while Romero’s men wandered to the west. These mixed with Castrillón’s men, creating a stagnant and unorganized mob. From his northern command post, Santa Anna witnessed the chaos before him. Outraged, he sent in the reserves with orders to drive the troops forward, with bayonets if necessary.

Pushed by the reserves, the soldiers finally reached the north wall. Being close to the wall provided some protection from the fort’s cannons, but now they suffered from the point-blank gunfire from the defenders on the wall. However, the men on the wall had to stand to fire their weapons, exposing them to Mexican musket fire. One of the first to fall because of this was William Travis. Standing to fire his shotgun, Travis was struck in the forehead by a Mexican musket ball. Stunned and dying, he collapsed beside one of the north wall cannons.

The Mexican soldiers faced another challenge. In the confusion of the attack, they’d lost their ladders, making it impossible for them to scale the wall. That was until they discovered an alternative solution. They found that the gaps between the logs of the wooden structure supporting the crumbling wall could be used as footholds. With these, they were able to climb up and over.

Santa Anna’s soldiers now poured over the north wall, their sheer numbers too much for the few defenders to hold back. Before they were completely overwhelmed, the men of the Alamo fell back to their second line of defense, the Long Barrack.

Made of stone, the Alamo’s Long Barrack was the oldest and strongest of all the buildings of the old mission compound. Stretching 192 feet along the east side of the main plaza, it was also the most defendable. As an additional defensive measure, the defenders had constructed makeshift barricades of rawhide and dirt in its doorways and cut gun ports into the building’s western wall. From the protection of the Long Barrack, the defenders made the plaza a killing ground as they fired on the Mexican soldiers coming off the wall. But the tide of the battle would again turn in Santa Anna’s favor.

The Mexican soldiers discovered that the defenders had made a fatal mistake. In their haste to exit the north wall, they’d neglected to spike their cannons. Driving a metal spike into the gun’s touch hole would have made it unusable. But now, the Mexicans turned the Alamo’s artillery on the Long Barrack.

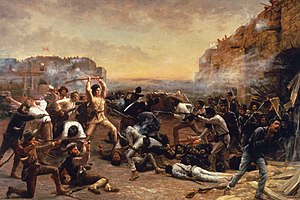

Once the doorways had been cleared, the soldiers stormed in. From the accounts of Mexican soldiers and officers who participated in the battle, the most horrific, vicious, and intense hand-to-hand fighting occurred within the Long Barracks dark and smoke-filled rooms. As the Mexicans moved through the building, they came across the garrison’s hospital on the second floor. It’s likely that the soldiers made quick work of the sick and wounded they found there.

At the Alamo’s southwest corner, the defenders manning the 18-pounder became aware of what was happening at the north wall and Long Barrack. To assist their comrades, they began to turn the big gun north. Which was precisely what Colonel Juan Morales was waiting for.

Seeing that the men on the wall were distracted, Morales and his small force of around one hundred men moved undetected along the line of jacales that the defenders neglected to destroy. But unlike the soldiers who attacked the north wall, his men hadn’t lost their ladders. Quickly, Morales’s men scaled the corner wall and captured the 18-pounder and the Low Barrack gatehouse. While searching the Low Barrack, Morales’s men came across Jim Bowie’s room. They found the famous knife fighter lying in his bed, sick and dying. Exactly how Jim Bowie died that morning is another mystery of the Alamo.

The forces of Santa Anna were now swarming into the Alamo on all sides. In the church, Captain Almeron Dickenson rushed into the sacristy; finding his wife Susanna, he said, “Great God, Sue, the Mexicans are inside the walls! All is lost! If they spare you, save my child.” Kissing his wife, he returned to the fight.

With the outer buildings now cleared of defenders, Santa Anna’s men converged on the fort’s Inner Courtyard. The Alamo’s Inner Courtyard was an enclosed area created by the Church on the east, the wooden Palisade on the south, a high connecting wall on its north side, and on the west, a six-foot-high “low wall” that stretched from the east corner of the Low Barracks to the southwest corner of the Long Barracks.

At this “low Wall,” the Mexicans once again encountered some of the fiercest fighting by the defenders. One of those defending this area was David Crockett. The men of the Alamo stood their ground, using knives, pistols, and even their rifles as clubs. But there were just too many Mexican soldiers.

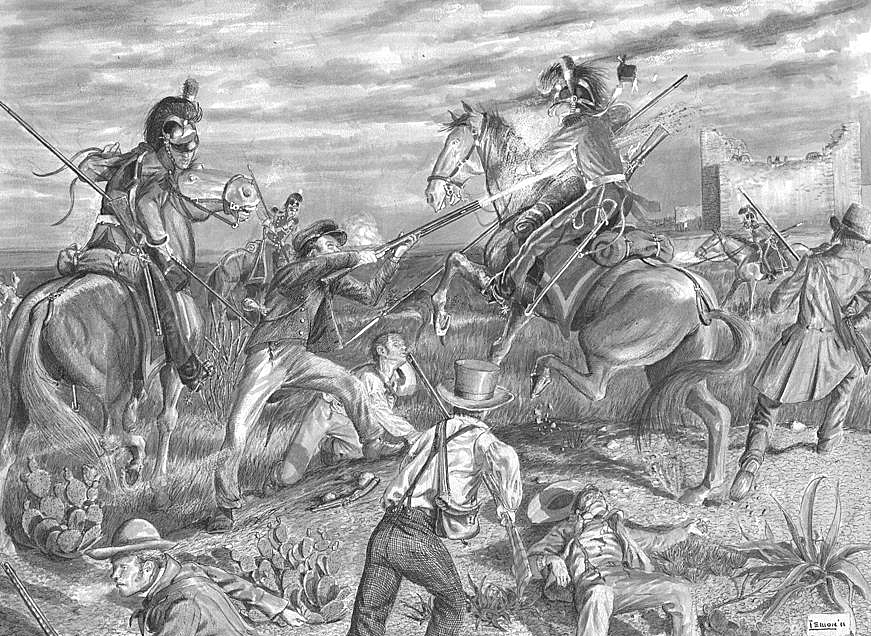

As the Mexicans closed in, a few defenders dropped back into the church, while another group, realizing that all was lost, retreated through a small gate, where the wooden palisade met the church’s southwest corner. From there, they dashed southeast, away from the Alamo. This is what Santa Anna envisioned and what General Sesma was prepared for.

Sesma’s calvary descended on them as they raced for cover across the open ground. Even with support from the cannons at the back of the church, the men on foot were no match for the lance-carrying mounted soldiers. After the battle, members of Sesma’s cavalry would tell how bravely these men fought.

The defender’s last stand was the Alamo’s church. From the church’s doorway, the defenders fired on the advancing soldiers from behind the protection of a sandbag barricade. The Mexicans quickly used the fort’s artillery to clear away this barricade. You can still see the artillery damage on the church’s façade.

With the doorway cleared, the Mexicans stormed into the church, finishing off the last of the defenders. Three defenders who died fighting in the church were James Bonham, Almaron Dickinson, and Gregorio Esparza.

In the semi-darkness of the church’s Sacristy, Susanna Dickinson and the other women and children listened in fear to the battle-crazed soldiers just outside their room. Then Dickinson heard her name called out in English. This came from a Mexican officer, believed to have been Juan Almonte. Under the protection of this officer, Dickinson and the others could leave the Sacristy.

One of the first things Susanna Dickinson saw when leaving the room was the bullet-riddled body of her husband, causing her to faint. Upon exiting the church, Dickinson saw another familiar face lying dead in the Inner Courtyard.

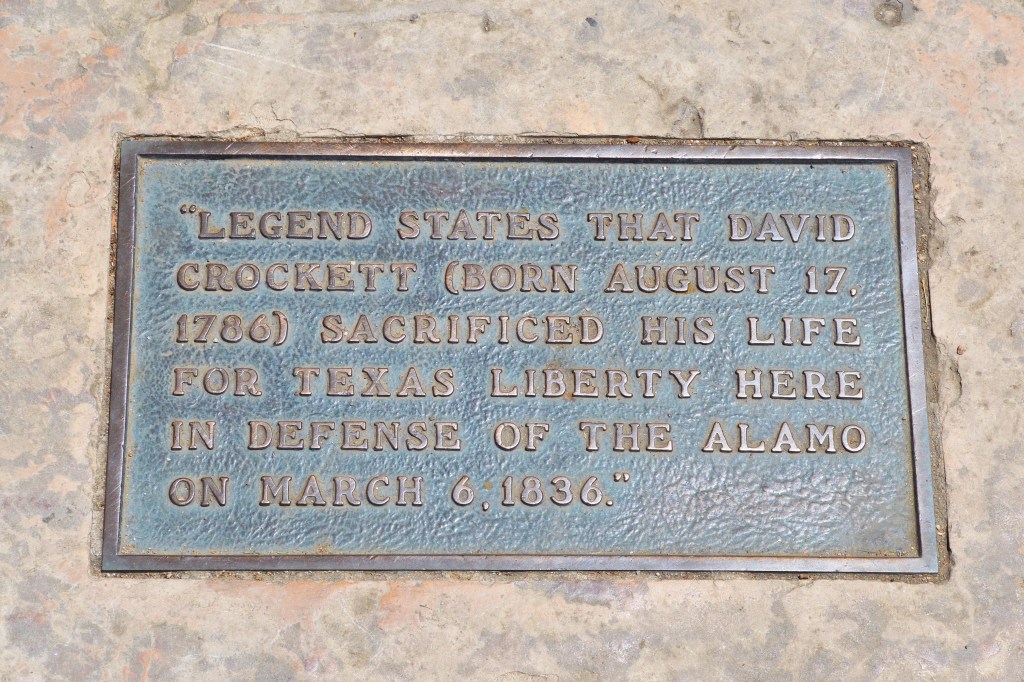

In an interview given before 1874, she said, “I recognized Colonel Crockett lying dead and mutilated between the church and the two-story barrack building.” She also remembered seeing his peculiar cap lying at his side.

In front of the Alamo church, embedded in the walkway, is a plaque indicating the general area believed to be where Dickinson saw Crockett’s body.

The Battle of the Alamo lasted barely ninety minutes and was over before the morning sun cleared the horizon.

The Post Battle

With the last of the defenders killed, the bloodlust of the Mexican soldiers began to fade. At that time the officers began assembling their men in ranks on the Alamo’s main parade ground. It was now past sunrise, and with the fort now secured and his troops in parade ranks, General Santa Anna entered the fort with great fanfare. Besides Santa Anna giving his victory speech to the assembled troops, another very controversial event most likely took place then.

Phil Guarnieri and Rick Range, in their book David Crockett Went Down Fighting: How We Know It, say that after Santa Anna’s speech, the captured defenders were brought before the general and then executed. But was Crockett one of them?

According to Guarnieri and Range, those executions took place long after Susanna Dickinson had already identified Crockett’s body in the Inner Courtyard.

What we do know is that Santa Anna showed a lack of remorse, not only for the Alamo’s defenders but for his men as well. This is shown when he remarked to Colonel Fernando Urriza, “Much blood has been shed, but the battle is over; It was but a small affair.”

Later, Colonel Almonte would remark that, “Another such victory would ruin them.”