Saturday, March 5, 1836: Travis’s Line

On the morning of March 5, the Alamo garrison was awakened by increased shelling from the Mexican artillery. With six artillery pieces targeting the north wall, each shot would send clouds of dirt, wood, and chunks of adobe raining into the fort.

The old mission’s north wall was in the worst condition of all its walls. Stretching 240 feet, it ran across the north end of the compound, with a height of twelve feet to just a foot or two. For decades, this adobe wall had been crumbling. Even the wood and earthen structure built by General Cos when the Mexicans occupied the Alamo did little to strengthen it. Trying to maintain this wall was the twenty-nine-year-old lawyer turned Alamo’s chief engineer, Green B. Jameson.

Jameson and his men worked feverishly day and night, constantly piling up earth, stone, and wood against the wall in the hopes of reinforcing it. But Jameson knew the north wall wouldn’t hold up when Santa Anna attacked.

That morning, as promised, Santa Anna informed his officers that the attack on the Alamo would commence the next day before dawn. There’s much speculation as to why Santa Anna ignored many of his officers’ suggestions to wait for Filisola. Mexican Lieutenant Colonel José Enrique de la Peña may have had the answer. In his memoir, With Santa Anna in Texas, la Peña believes Santa Anna attacked on March 6 because he feared Travis would surrender, thus robbing him of a glorious and bloody victory.

In preparation for the attack, Santa Anna ordered all shelling on the Alamo to cease at around 5 o’clock that afternoon. He hoped the quiet would cause the exhausted defenders to fall into a deep sleep, allowing him to catch them by surprise when he attacked. And it was during this lull that a legend, or a myth, was born.

William Travis had been encouraged by the arrival of the thirty-two men from Gonzales and Major Williamson’s letter. But now, five days later, with no sign of help and the significant reinforcements Santa Anna received on March 3, he knew an all-out attack would soon be coming and that help wouldn’t arrive in time. It was time to talk to his men.

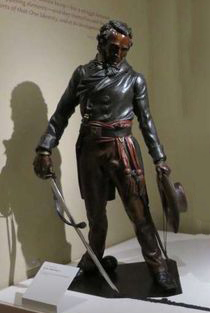

According to legend, Travis called the garrison together and informed them of his doubts and fears. He then told them he’d remain at his post but wouldn’t expect them to do the same. Travis then drew his sword and cut a line in the dirt in front of his men. He then asked that whoever chose to stay with him and fight to the death cross over the line. And as the legend goes, all but one crossed over. That one man is said to have been Louis “Moses” Rose. This story is somewhat supported by eyewitness Susanna Dickinson.

In an 1877 interview, Susanna Dickinson tells what she witnessed on the afternoon of March 5. According to Dickinson, “On the evening previous to the massacre, Col. Travis asked the command that if any desired to escape, now was the time to let it be known, & to step out of the ranks. But one stepped out. His name to the best of my recollection was Ross.” Although Dickinson doesn’t mention a line, she does say that Travis did call the men together and asked anyone who wanted to leave to step forward, of which one did. And the fact that she had his name as Ross instead of Rose doesn’t make what she saw less valid.

Travis’s “Line in the Sand” is the cornerstone of the Alamo’s “last stand” mystique. In fact, there’s a brass rod embedded in the walkway in front of the Alamo church that commemorates this event. And yet this tale of sacrifice is wrapped in controversy, with most historians considering Travs’s line in the sand but a myth.

Could Travis have drawn a line? If you consider the man who wrote the “Victory or Death” letter, drawing a line in the sand fits him perfectly. Line or no line, as Dickinson stated, the majority of the garrison had chosen to stay. Travis and his men would write their final letters to friends and family that evening, which supports the idea that the regiment had made some sort of decision.

Instead of another plea for reinforcements, Travis composed his last will and wrote a letter to his son. To carry these final messages from the doomed company, Travis called on twenty-one-year-old James L. Allen. Shortly after dark, riding bareback, the young Allen slipped through the Alamo’s gate, disappearing into the darkness. James L. Allen would be the last to leave the Alamo.

Allen would fight at the Battle of San Jacinto, become a Texas Ranger, and serve as Mayor of Indianola, Texas. In 1901, at 86, he rejoined his Alamo comrades.

Later that night, Travis went around the compound encouraging his men. Upon entering the Alamo’s church, he found Susanna Dickinson. Threading a string through his cat’s eye ring, Travis placed it around Susanna’s two-year-old daughter Angelina’s neck. Returning to his quarters on the west wall, Travis finally laid down at around 4 a.m. on March 6. But his rest would be brief.