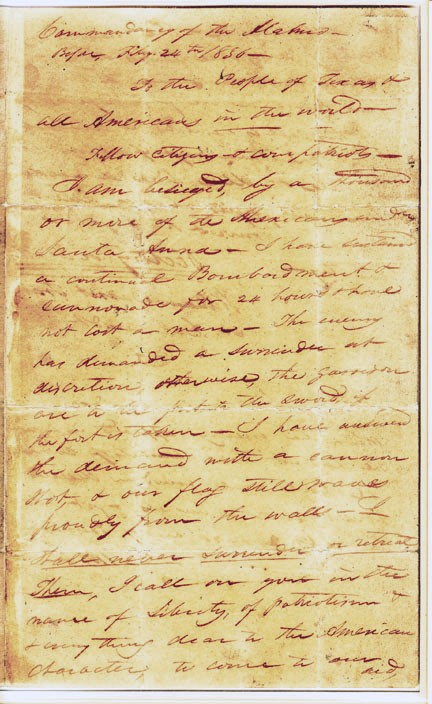

February 24, 1836: To the People of Texas & All Americans in the World

As the sun rose over the Alamo on the second day of the siege, Lt. Col. William Barret Travis watched the continuous stream of Mexican soldiers marching into Béxar. Travis knew that his small garrison of less than two hundred was already outnumbered, and it was getting much worse by the minute.

While the Mexican army hadn’t yet attacked, Travis watched as they did reconnaissance of the Alamo’s defenses. In addition, the Mexicans were constructing artillery placements to the south, west, and north of the fort. But even though this was worrisome, there was another crisis in the Alamo that he had to face.

Jim Bowie, the legendary knife fighter and co-commander of the Alamo, had been ill for some time. However, that morning he couldn’t even get out of bed. Calling Travis and Crockett to his room on the west wall, he told them he could no longer share command. In addition, since Bowie’s illness was “a peculiar disease of a peculiar nature,” the garrison doctor feared it could be a very contagious typhoid or tuberculous. The doctor strongly suggested that Bowie be quarantined away from the rest of the garrison. Bowie was moved to a small room in the Low Barrack building just to the left of the main gate.

With Bowie out of commission, the total weight of the Alamo’s command now fell on the young Travis.

Watching the numbers of enemy troops growing and new cannon placements, Travis knew he needed to get out an appeal for assistance while he could. Going to his quarters on the west wall, he composed a letter that would become the most famous letter in Texas history and a symbol of the determination of the Alamo defenders.

Judge for yourself:

To the People of Texas & All Americans in the World:

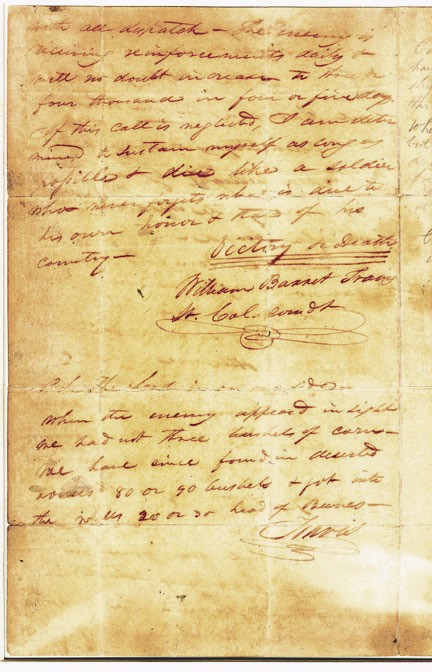

Fellow citizens & compatriots. I am besieged, by a thousand or more of the Mexicans under Santa Anna. I have sustained a continual Bombardment & cannonade for 24 hours & have not lost a man. The enemy has demanded a surrender at discretion, otherwise, the garrison are to be put to the sword, if the fort is taken. I have answered the demand with a cannon shot, & our flag still waves proudly from the walls. I shall never surrender or retreat. Then, I call on you in the name of Liberty, of patriotism & everything dear to the American character, to come to our aid, with all dispatch. The enemy is receiving reinforcements daily & will no doubt increase to three or four thousand in four or five days. If this call is neglected, I am determined to sustain myself as long as possible & die like a soldier who never forgets what is due to his own honor & that of his country—

VICTORY OR DEATH

William Barret Travis Lt. Col. comdt.

This simple letter, by the commander of an insignificant little garrison out on the western frontier, was more than just a plea for help; it was a profound statement of patriotic honor and commitment.

His call of “…everything dear to the American character” should not be seen as Travis just echoing those feelings of his time and his place, but a reminder of what the American character is: fighting for what’s right, liberty against tyranny, no matter what the odds, and no matter what the cost may be.

Above, I left off his P.S. at the end to focus on the historical and patriotic tone of his letter’s main body.

P.S. The Lord is on our side. When the enemy appeared in sight we had not three bushels of corn. We have since found in deserted houses 80 or 90 bushels and got into the walls 20 or 30 head of Beeves. Travis