Even those unfamiliar with Texas history and the Battle of the Alamo know, “Remember the Alamo.” However, you may not be aware of the second part of that Texan battle cry of San Jacinto, “Remember Goliad.”

What would become known as the Goliad Massacre is often overshadowed by the last stand at the Alamo. However, what took place only twenty-one days after the fall of the Alamo would have a much more significant impact on the fledgling Texian army and a greater loss of life than at the Alamo.

But most of all, Goliad shows the bloodthirsty and cold-heartedness of Mexican General Antonio López de Santa Anna.

We begin our story of the Goliad Massacre on the night of March 26, 1836.

“Home Sweet Home”

A little over 300 Texans sat as prisoners of the Mexican army in the Presidio La Bahia in Goliad. This Presidio had been the Texian’s Fort Defiance just a few days earlier; now it was their prison. They had been defeated by the Mexican forces of General José de Urrea when caught on the open prairie near Coleto Creek while retreating to the town of Victoria to join with Gen. Sam Houston.

Although they’d fought bravely for two days, their situation was dire: They were completely surrounded, outnumbered, and had minimal cover to protect them. When their commanding officer, Col. James W. Fannin, became wounded, they decided to seek terms of surrender.

General Urrea, a good and honorable officer, personally dealt with Col. Fannin on the surrender. While Fannin asked for a surrender with terms, Urrea informed him that was not possible. He told Fannin that he was bound by the Mexican government’s congressional decree and Santa Anna’s orders to accept only an unconditional surrender. The Presidio La Bahia/Fort Defiance in Goliad Texas. Photo from Wikipedia.

However, Gen. Urrea reinsured Fannin that he’d personally intercede on their behalf with Gen. Santa Anna and that those who’ve submitted themselves to the “disposition of the supreme government” have always been treated fairly, with the honor of a soldier. Not having much of a choice, Col. Fannin agreed to the unconditional surrender. However, Fannin failed to tell his officers and men that the surrender was unconditional and their fate was in the hands of Santa Anna.

The Texians were in a good mood on the evening of March 26, 1836. Rumors said they would be paroled and marched to the Texas coast to board ships back to the United States. So excited were these men by this prospect that they joyously sang the popular 1800s song “Home Sweet Home” that night. But they didn’t know that Gen. Urrea and his officers were disputing Santa Anna’s order, demanding that they be executed.

Finally, in disgust, Urrea returned to his campaign along the Texas coast, leaving Colonel José Nicolás de la Portilla to carry out Santa Anna’s dirty order.

March 27, 1836- Palm Sunday

At sunrise on March 27, 1836, which just happened to be Palm Sunday, the prisoners were awakened by the Mexican soldiers. Those with wounds that kept them from walking, including Col. Fannin, were left behind at the fort. The rest of the prisoners were taken out and divided into three columns. These columns were sent off in three different directions from the Presidio, with Mexican soldiers marching on both sides.

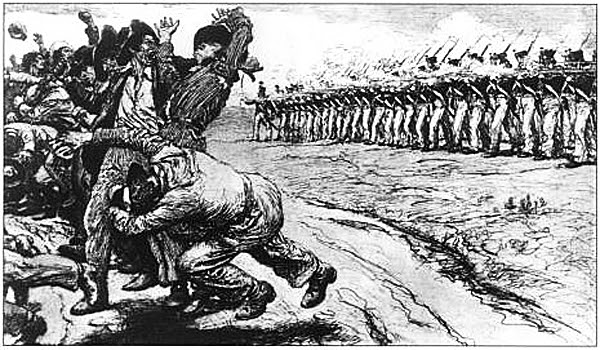

When the columns were less than a mile from the fort, they came to a halt at predetermined spots. The Mexican soldiers on the right side of the columns countermarched and formed up with the guards on the left side, creating a firing line. By this time, most of the Texans had realized what was coming. The order was given to aim and fire into the columns.

Because of the point-blank closeness of the Mexican soldiers to the men in the columns, nearly all the Texians fell in that first round of musket fire. Those who somehow survived that first volley were quickly pursued and slaughtered by bayonets, lances, or gunfire. Even Col. Fannin and the wounded back at the Presidio were not spared. All were executed, some in their beds.

However, of the 425 to 445 Texians who were marched out that morning to be slaughtered, twenty-eight amazingly escaped the carnage. In addition, a few men who had been captured at the Battle of Refugio and now worked as blacksmiths and wheelwrights for the Mexican army were also spared.

There was also a person who was very instrumental in saving Texians at Goliad.

The Angel of Goliad

Francisca Alavez, the wife of Mexican officer Captain Telesforo Alavez, is credited with saving the lives of Texian prisoners from the Palm Sunday massacre. Francisca Alavez rescued twenty Texians by convincing Mexican officers that they were essential to the Mexican Army as physicians, orderlies, and interpreters. It’s also said she helped others to sneak out during the night. For this, she is known as “the Angel of Goliad.”

In addition to Goliad, Francisca also helped to save another 106 Texans in the town of Victoria.

The Disposal of the Texian Dead at Goliad

As it was with those who fell at the Alamo, the bodies of those killed at Goliad were also cremated on a funeral pyre or pyres. However, the wood used for the Goliad pyre(s) was said to be still green. This kept the Goliad pyre(s) fires from getting as hot as those on the Alameda, resulting in the bodies at Goliad not being wholly consumed, causing a gruesome sight and smell for the town’s residents.

Again, as with the Alamo’s fallen, the remains of those killed at Goliad also lay unburied and open to the elements. But unlike the remains of the Alamo defenders, which lay exposed for a year, those murdered at Goliad had a slightly different ending.

Just a few months after the massacre, Texas General Thomas J. Rusk visited Goliad and gathered up the remains of those murdered. There, not far from the Presidio La Bahia, with full military honors, Gen Rusk buried the remains in a shallow common grave. But, Rusk neglected to mark the grave site.

The location of the mass grave was unknown until 1930 when a group of Texas Boy Scouts discovered fragments of charred bone that had been unearthed by animals. Those fragments were then authenticated by historians Clarence R. Wharton and Harbert Davenport of the University of Texas and proved to be those murdered in the Goliad Massacre.

In 1936, a pink granite monument was constructed on the grave site to celebrate Texas’s centennial. The memorial to those murdered at Goliad was officially dedicated on June 4, 1938, and stands today for all of us to “Remember Goliad.”

How Many Were Killed in the Goliad Massacre?

By using Fannin’s muster records and excluding those who either escaped or were spared from execution, it’s accepted that 342 men had been massacred on that Palm Sunday morning of March 27, 1836, which was significantly more than those who fell at the Alamo.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

The foundation for this article is a Facebook post I wrote a few years back. At that time, I didn’t cite my sources, and since that was a time ago, I’m unable to cite them now. However, these are the sources I used to update this post.

“Battle of Coleto.” Wikipedia , Wikipedia , Feb. 2025, en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Coleto.

Davenport, Harbert, and Craig H. Roell. “Goliad Massacre.” Texas State Historical Association, Texas State Historical Assocation, 22 Mar. 2018, http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/golias-massacre.

Roell, Craig H. “Coleto, Battle Of.” Texas State Historical Association , Texas State Historical Association , 4 Aug. 2020, http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/coleto-battle-of.

Wikipedia . “Goliad Massacre .” Wikipedia , Wikipedia, Feb. 2025, en.m.wikipedia.org/wik/Goliad_massacre.