Thursday, February 25, 1836: The Mexicans attack

February 25 was a little warmer, a welcome relief for Santa Anna’s soldiers from central Mexico.

Shortly after dawn, the Mexican artillery began shelling the Alamo. This came from the batteries located on the western side of the San Antonio River and the newest battery south of the Alamo in the Village of La Villita. However, the cannons of the Alamo remained silent, choosing to conserve the limited gunpowder.

At around 9:30 am, Santa Anna ordered General Castrillón to move the Cazadores and Matamoros Permanent Battalions across the river into La Villita. The total number of soldiers is believed to have been 400 to 450 men. From La Villita, Santa Anna ordered Castrillón to attack the Alamo’s south wall.

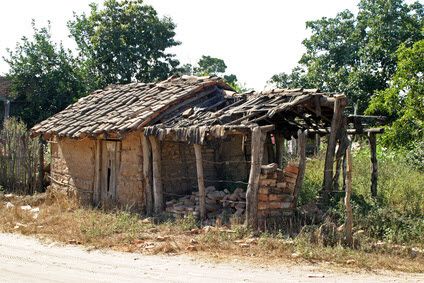

The Mexican soldiers had to pass through the Pueblo de Valero to get to the Alamo. This small community was settled when the Alamo was the San Antonio de Valero Mission. Pueblo de Valero was an impoverished village, with most of the houses being what’s known as “jacales.’” These jacales were mainly constructed of wood and mud. But these tiny houses of Pueblo de Valero would play a significant role in the Alamo story.

The sentries on the Alamo’s south wall watched as the Mexican troops crossed the river on the footbridge. When the soldiers began moving toward the fort, they sounded the alarm. The garrison quickly rushed to the south wall with rifles in hand.

Travis sent a detachment into the trenches outside the wall to prepare for the attack, and the 18-pound cannon was turned toward the advancing Mexicans. Travis ordered his men to fire when the soldiers were within fifty to one hundred yards of the Alamo. This first firefight lasted for nearly two hours. But finally, the defenders were able to drive the Mexicans back to La Villita. Travis wrote of his larger-than-life co-defender’s actions, “The Hon. David Crockett was seen at all points, animating the men to do their duty.”

Santa Anna hadn’t lost everything on that morning of February 25. He established his artillery and infantry on the Alamo’s side of the river and learned a critical lesson; the Alamo defenders were quite effective with their rifles and cannon, so take them seriously.

Although the defenders won this battle, it did reveal a significant weakness in the fort’s defenses, the jacales. When the defenders had opened fire, some Mexican soldiers took cover in the jacales. And from this protection, they returned fire. Travis knew that those nearest the fort had to be destroyed. He sent Charles Despaller and Robert Brown out to burn them to the ground.

That evening, Travis sent out another plea for help. And he wanted this appeal to get directly into General Sam Houston’s hands. Travis called one of his most trusted men to carry it, Tejano leader Juan Seguín. Before Seguín left the Alamo, he promised his men that he’d soon return. However, he couldn’t keep his promise.

Besides the battle, another incident is said to have occurred that day. While the Mexican soldiers were searching the jacales, they discovered that not everyone living in Pueblo de Valero had left. These citizens were rounded up and taken before Santa Anna. As the story goes, a widowed Seňora and her teenage daughter were among them. It was also said that this Seňorita was very beautiful and caught the eye of Santa Anna. However, the mother refused to let Santa Anna have his way with her daughter without marriage. Not to be denied what he desired, Santa Anna concocted a ruse. He had one of his officers pretend to be a priest and conduct a false marriage ceremony.

This fake wedding is said to have happened later in the siege, and the honeymoon lasted until Santa Anna left San Antonio late in March to chase Houston. As the tale goes, the young bride was shipped off to San Luis Potosi, which is in the interior of Mexico. It’s also said that she bore Santa Anna a son, which he most likely never saw.