Photo by author, taken in 2018 during Fiesta.

It was during my first visit to the Alamo in 1986 that I heard it; I remember it well; it came from a boy, about seven or so years old, standing there in the middle of the Alamo church with his father, mother, and little sister. He was looking up at his dad with a very confused stare as he asked his question, “Daddy, is this all there is?”

Sadly, that’s the way too many visitors saw the Alamo: Just the one small building, sitting in the middle of a very busy city, totally ignoring the Long Barracks next to it. It’s no wonder that many felt cheated. In fact, the Alamo was often listed as a tourist trap.

The Daughters of the Revolution Texas (DRT) did a good job of creating the Alamo’s church as the “Shrine to Texas Liberty.” Still, they missed promoting the historic Alamo, wth most of it hidden and buried beneath one of San Antonio’s most popular plazas and commercial buildings.

In this post, I’ll present how different groups began to put pressure on the City of San Antonio and the State of Texas to take action, not only to save and restore the frail Alamo church and Long Barracks, but also to restore the fort’s original footprint and the dignity of that hallowed ground.

Also, I’ll present some early proposals for reclaiming the Alamo’s original compound that would eventually lead to one of the most historic agreements in the 300-year history of the Alamo.

Davy Crockett returns to the Alamo

Photo taken from the YouTube video of Parker’s 1994 Alamo Society’s symposium appearance.

In 1994, Davy Crockett (Fess Parker) returned to the Alamo. Parker was the guest of honor at the Alamo Society’s symposium that year. During his presentation, Parker addressed what he called the “current battle going on across the street,” referring to Alamo Plaza. He pleaded that the city, county, and state, “should be large enough, wise enough, and creative enough, to pull back away from the Alamo, as we see it across the street, the chapel, and give it space.” Parker went on to say he felt that politics should be put aside so that the whole story of the Alamo can be told, and that none of the participants in that battle should be left out, “…that struggle is universal.”

During the question and answer portion of Parker’s presentation, a gentleman from San Antonio stood and informed the group that Parker had helped to found the Alamo Foundation, a group dedicated to the historical preservation of Alamo Plaza. He also added how the foundation had recently helped fund archaeological studies on Alamo Plaza. He then went on to tell of a newly formed Mayor’s committee, which, along with other civic groups, was working together to restore Alamo Plaza, and that, “In the next few years we’ll see our dream come about.”

The Alamo Plaza Study Committee of 1994

Photo from the June 8, 2017, San Antonio Express-News article, Former EN columnist wanted park in place of part of Alamo Plaza, by Scott Huddleston.

The committee that the gentleman was referring to was the Alamo Plaza Study Committee, formed by then-Mayor Nelson Wolff, along with the City Council. This committee’s stated purpose for the city-owned plaza was:

- Determine the best way to design the closing of Alamo Plaza East on a permanent basis:

- Research available data to establish historical information concerning Alamo Plaza:

- Review and evaluate different options to better define and represent the battle and other periods of history of the plaza, including past and present studies:

- Prepare recommendations for City Council regarding the best long-term plans for the Plaza, including the appropriate historical interpretation of Alamo Plaza and recognition and respect for area burials, signage, pedestrian and vehicular circulation, visitor loading and unloading, access for the disabled, and other pertinent issues:

- Submit the committee’s written report of its findings and recommendations to the City Council by October 1, 1994.

The City Council appointed twenty-four members to this committee, composed of representatives from various San Antonio civic groups, the Daughters of the Republic of Texas, local property owners, historians, and one media representative.

The Committee held its first meeting on March 10, 1994, at the Menger Hotel, next door to the Alamo. The committee worked for six months in preparing their list of key recommendations, which included: closing the streets to traffic around the Plaza, removing the street curbs, and creating a visitor center/museum.

The committee also recommended that if any “replicated” buildings or walls of the old Alamo fort were constructed, they should be of a different material and not the same color as the two original Alamo buildings. Their reasoning was that they didn’t want to give “a false sense of history” with the replicates.

However, the major eyesores that most visitors to the Alamo complain about — the businesses along the west side of Alamo Plaza — the committee firmly chose to oppose the removal of those businesses and buildings. Perhaps this was because some of those business and property owners sat on the committee. Also, the city only had a limited say on these privately owned properties and businesses.

After six months, they submitted their report, for which they were thanked by the mayor and council for their time and hard work. In the end, the 1994 Alamo Plaza Study Committee’s report was shelved, with nothing being accomplished, not even removing the traffic from around the Alamo.

However, even though the 1994 committee’s recommendations went nowhere, there was one proposal created by that committee’s sole media member that still resonates today.

David Richelieu’s “Alamo Park”

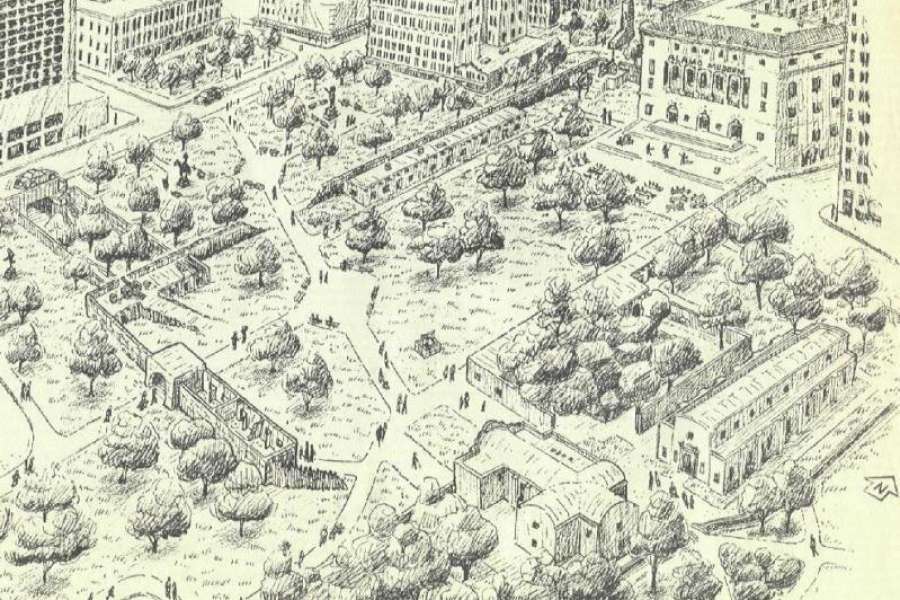

Art from the June 8, 2017, San Antonio Express-News article, Former EN columnist wanted park in place of part of Alamo Plaza, by Scott Huddleston.

David Anthony Richelieu, then a columnist for the San Antonio Express-News, conceived of a plan that would recapture the footprint of the original Alamo compound and transform it into a historical park. Richelieu felt that his park would help visitors to visualize the extent of the Alamo fort, while still bringing reverence to its hallowed grounds.

Richelieu’s plan called for closing the streets surrounding the Alamo and Alamo Plaza, then tearing up all the concrete curbs and asphalt. He would then replace the streets with grass lawns, trees, and flagstone walkways. His plan also called for expanding the borders beyond the original compound’s footprint: west to Losoya Street, north across E. Houston Street, and south to Blum Street.

Richelieu’s plan called for the demolition of the Woolworth, Palace, and Gibbs buildings and the relocation of the Crockett Building. This would allow for the construction of a replica of the Alamo’s west wall and buildings. In addition, his plan also included the construction of replicas of the fort’s Low Barracks main gate and its cannon platforms and ramps on the southwest and northwest corners. Richelieu also called for relocating the Alamo Cenotaph to the north end, outside of the fort’s original footprint.

Richelieu proposed leasing the first floor of the massive Hipolito F. Garcia Federal Building and Courthouse, which sits where the Alamo’s north wall was, to house a permanent Alamo museum. Inside the museum, he called for a replica of the north wall and its cannon battery to be built on the exact spot where it had stood and where Travis fell.

Photo by author.

To add an extra historical dimension to his park, he wanted statues of famous Alamo defenders and mission-period figures placed throughout.

Although David Richelieu’s vision never had any serious consideration in 1994, it’s interesting to note how many of Richelieu’s ideas would resurface in future proposals.

It would take seventeen years after Fess Parker made his plea before any movement to reclaim Alamo Plaza would take place, then only after organizations became more vocal in their fight for the Alamo and its battlefield plaza.

There was one group that was clearly heard with their cry: REMEMBER, RECLAIM, RESTORE.

The Alamo Plaza Project

Art taken from video.

On March 6, 2011, during the 175th Anniversary of the battle, my wife and I were in Alamo Plaza when we noticed a small group standing near the stone wall where the Alamo’s main gate had been. This group seemed to be collecting petition signatures, and what attracted me to go over and talk was their sign, which read: REMEMBER, RECLAIM, RESTORE.

These were members of the Alamo Plaza Project; their goal is to recapture the historic original Alamo compound and to bring reverence and respect to that hallowed ground. And of course, I added my name to the petition.

The Alamo Plaza Restoration Project is the campaign led by the non-profit, Texas History Center at Alamo Plaza Inc. The organization’s 2011 president Jack Cowan, a San Antonio resident, has described the Alamo as still being under siege; not by the Mexican army, but by the city and the businesses invading the historic site. “The Alamo is the number one historic site in Texas,” states Cowan, “and San Antonio treats it like a stepchild. It doesn’t get any of the respect it deserves.”

This group has been one of the most influential in pushing for significant changes to Alamo Plaza. Their aim to “raise the consciousness” of the plight of the historic Alamo has been significantly promoted by their business manager, filmmaker Gary Forman. Through his production company, Native Sun Productions, Forman has produced a series of videos focused on the lack of respect given to the Alamo battlefield. In his video, Alamo Plaza: A Star Reborn, he presents the organization’s own visionary plan for restoring the Alamo battlefield.

The Alamo Plaza: A Star Reborn design is in many ways similar to David Richelieu’s: removal of traffic from the streets around the Alamo and Plaza, relocation or demolition of the commercial buildings on the west side of Alamo Plaza, construction of replicas of the Alamo’s west wall, buildings, and the fort’s 1836 main gate and south wall.

In this plan, the Hipolito F. Garcia Federal Building would be occupied entirely, not just its first floor. Inside would be a major state-of-the-art multimedia center and museum, and as in Richelieu’s plan, there’d also be a reconstructed north wall and cannon battery.

Also in this plan, as in Richelieu’s, the Alamo Cenotaph would be relocated, this time to the south end of the Plaza, outside of the Alamo’s original footprint.

But unlike Richelieu’s vision, the Alamo Plaza Project’s concept would not be for a park, with walkways and trees. Theirs was for a vast open space where the compound had been, surrounded by a reconstructed replica of the fort’s main gate, the Alamo Church and Long Barracks, as well as the reconstructed west wall, and at the north end, the Alamo museum inside the federal building.

In Forman’s 2013 video, Alamo Plaza Project, Dallas resident Rick Range makes a heartfelt call for the State of Texas to take action:

“I believe that the State of Texas needs to step in, and take control of this area, and make it into what it should have been for decades past. It’s a disgrace what’s been allowed to happen to this area. Ah, it’s beyond belief, it’s disrespectful, and I would love to see the State of Texas step-up and do what needs to be done.”

Two years after Range’s call for action, and after viewing the video Alamo Plaza: A Star is Born, with its visionary design, the Texas Legislature voted to provide funding to begin the restoration process of Alamo Plaza and to repair and preserve the Church and Long Barracks.

The State of Texas Steps Up, in a BIG Way

As I wrote, the State of Texas has owned the Alamo Church and Long Barracks, as well as the grounds behind them, for decades. But for the most part, the state took a “hands-off” attitude on its upkeep and management, leaving that at first to the City of San Antonio and then to the Daughters of the Republic of Texas (DRT).

In the late 1980s, the state began getting pressure from many special interest groups to transfer control of the Alamo from the DRT to the League of United Latin American Citizens, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, and then the Texas Historical Commission. However, the DRT retained control of the Alamo complex, due to support from the City of San Antonio and then Governor George W. Bush.

In 2010, after getting complaints and reports of negligence and mismanagement, the Texas Attorney General conducted an investigation into the administration of the Alamo by the DRT. His findings did indeed show that the DRT had been negligent in its fiduciary duties. With this report, the state legislature transferred oversight of the Alamo to the General Land Office (GLO). This started a chain of events that would alter the Alamo’s future.

The Texas General Land Office

The Texas state bill that allowed for the transfer of the Alamo from the DRT to the GLO was HB 3726. This bill also gave the GLO the authorization to partner with, or to create, non-profit organizations to help manage, or to support, their efforts with the Alamo. This ability would significantly guide the developing future of the Alamo.

The first organization to be created under HB 3726 was the Alamo Endowment in 2012. The Alamo Endowment’s primary mission was to create an endowment fund and to spearhead capital fundraising drives, which would allow the Alamo complex to operate self-sufficiently. Although the Alamo Endowment is a private non-profit organization, it’s still overseen by the GLO.

The first major shock came in March of 2015, when Commissioner George P. Bush, nephew of George W. Bush, announced that the GLO would take over the day-to-day operations of the Alama from the DRT, thus ending their more than a century of custodianship.

In defense of the DRT, this organization had fought to save the Alamo’s buildings, and for decades, preserved their dignity when others, including the city and state, were indifferent. And yes, their oversight greatly lacked what was needed to maintain and preserve these old and historic treasures, but they made commendable efforts. What if they had more guidance and support in the care of the Alamo? Would their tradition have continued?

The next significant development came in October of 2015, when the GLO paid $14.4 million for the purchase of the Woolworth, Palace, and Crockett buildings. This came as a big surprise to many, especially Davis Phillips, owner of Phillips Entertainment, which operated the businesses drawing the most criticism for their affront to the dignity of the battleground.

Photo by the author.

Although the GLO and the building lessees said the long-term leases would be honored, the writing is still on the wall.

The nearly 100,000 sq. ft. of space that these buildings occupied, as well as their sitting on the fort’s west wall and where Travis’s headquarters had been, was crucial to any redevelopment plans for the plaza.

The biggest hindrance in the past for any true restoration of the Alamo’s 1836 compound had been that the property was owned by four different entities: the State of Texas, the City of San Antonio, the Federal Government, and commercial property owners. Now, with the GLO’s purchase of the buildings along the west side of Alamo Plaza Street, the number of entities involved was cut to just three: the State of Texas, the City of San Antonio, and the Federal Government. However, the majority of the Alamo’s 1836 footprint was owned by two: the state and the city. And this is where the provisions of HR 3726 came further into play. It gave the GLO the legal authority to enter into what would be a very historic agreement with the City of San Antonio.

A Historic Agreement

As I wrote earlier in this post, in 2014, the City of San Antonio established the Alamo Citizens Advisory Committee, whose mission was to update the 1994 Alamo Plaza Study Committee’s report and recommendations. Their task would also include creating a vision and guiding principles for Alamo Plaza, as well as developing a master plan for its redevelopment.

That December, the City Council adopted the committee’s vision and guiding principles; however, before they could move forward with their plan, the GLO approached them with another proposal. That by working together on a common master plan, it would be in the best interests of the Alamo.

So in October of 2015, the San Antonio City Council passed a cooperative agreement to work with the GLO and the Alamo Endowment Board to develop a joint master plan, which would not only include Alamo Plaza, the Alamo complex, but also the greater Alamo Plaza Historic District.

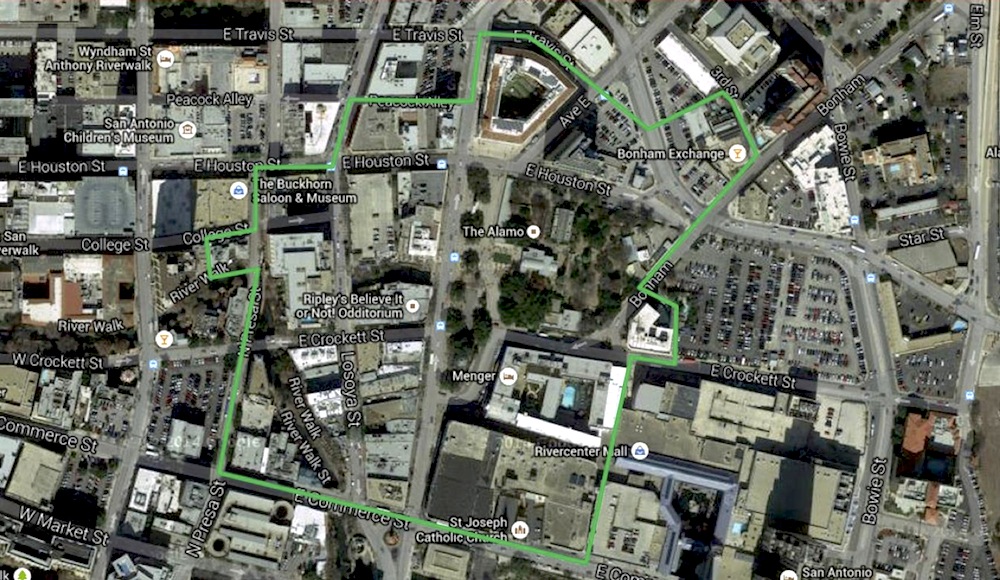

Map from the Center City Development and Operations Department.

The Alamo Plaza Historic District was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1977. This district roughly includes Broadway/Losoya Street, E. Commerce Street, Bonham Street, and Travis Street.

The agreement between the city and state outlined the responsibilities and management roles of each party in the development and implementation of a master plan. Also, the Advisory Committee was expanded to include appointees by the GLO.

This agreement also dictated that the Committee’s Vision and Guiding Principles would be the basis for developing the new master plan. To help manage the planning and development of the Master Plan, they formed the Alamo Management Committee.

The Management Committee selected the Philadelphia, Pennsylvania firm, Preservation Design Partnership LLC (PDP), under Dr. George C. Skarmeas, to lead in the planning process. PDP, a rather small historic preservation and architectural firm, and Dr. Skarmeas have an impressive resume when it comes to planning and designing historic sites. They were known for their work on the United States Supreme Court building in Washington, DC, Thomas Jefferson’s Virginia Capitol, and the Cincinnati Museum Center at the Cincinnati Union Terminal, to name a few. Also, Dr. Skarmeas was appointed Commissioner on the US Commission of UNESCO, which deals with World Heritage sites. The Alamo and the other San Antonio Missions were added as UNESCO World Heritage sites in 2015.

Even though PDP wasn’t a Texas firm, it did seem like a good choice. All the pieces seemed to be in place. A reputable preservation firm had been hired, and for the first time since 1836, the entire Alamo compound was under the direction of only one group. What could go wrong?

But as columnist Glenn Effler wrote in his 2017 San Antonio Express-News article, “Reimagine the Alamo? Ok, but the master plan doesn’t:”

My next post: The History of the Alamo, Part XII: Remembering the Alamo

Some of my sources:

Casey, Rick. “A Modern-Day Surrender at the Alamo.” The Rivard Report, The Rivard Report, 9 Oct. 2018, therivardreport.com/a-modern-day-surrender-at-the-alamo/.

Huddleston, Scott. “Former EN columnist wanted park in place of part of Alamo Plaza.” San Antonio Express-News, San Antonio Express-News, 8 June 2017, http://www.expressnews.com/news/local/article/Former-EN-columnist-wanted-to-replace-part-of-11206678.php.

Tamari, Nastassia. “Restoring Alamo Plaza.” ABC 7 News, ABC 7 Amarillo, 13 Mar. 2011, abc7amarillo.com/news/local/restoring-alamo-plaza.

“Alamo Mission in San Antonio.” Wikipedia , Wikipedia, 23 2019, en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alamo_in_San_Antonio.

Effler, Glenn. “Reimagine the Alamo?… Ok, but this master plan doesn’t.” MySA, Express-News, 29 Apr. 2017, http://www.mysanantonio.com/opinion/commentary/article/Reimagine-the-Alamo-OK-but-this-master-plan-11107036.php.

“Alamo Citizens Advisory Committee.” Center of City Development & Operations Department, City of San Antonio, http://www.sanantonio.gov/CCDO/Resources/Alamo-Advisory-Committee. 2019.

The Alamo Plaza Project. “A Star Reborn.” Alamo Plaza Restoration Project, Alamo Plaza Project, http://www.alamoplazaproject.com/. 2019.

Alamo Plaza Project. Created by Gary Forman, Native Sun Productions , 4 Dec. 2014. YouTube.

Alamo Plaza: A Star Reborn. Created by Gary Forman, Native Sun Produictions, 18 Nov. 2011. YouTube.

Fess Parker Visits Alamo Society’s 1994 Symposium. Royal Bard, 20 Feb. 2019. YouTube.