By the late 1800s, the urban sprawl of San Antonio, created by Samuel Maverick and other developers, had all but strangled the hallowed ground of the Alamo battlefield. The mission/fort compound was soon forgotten, where so many brave men had fought and died, their blood baptizing its very earth, was nothing more than just another city plaza. All that was left of the famous fort were three buildings, and even those would become lost to commercial development.

In this post, I’ll cover the Alamo’s post-army period when the buildings that remained continued to fall victim to further degradation, as developers, the City, and the State saw the Alamo’s grounds as little more than for commercial use.

Where Jim Bowie died

The Alamo’s main gate building was no longer called the Low Barracks, but the Galera. It was there in a room to the right of the gate that James Bowie was killed in his sickbed during the 1836 battle. Now, without its connecting walls, it sat alone in the middle of the vastness between the de Valero and Alamo Plazas.

To City officials, the Galera was nothing more than an eyesore. Besides sitting in the middle of two large plazas, a large pond would form when it rained, where the main gate’s entrance had been. This was likely caused by the depression left by the fort’s defensive Lunette, which the Mexican Army had filled in after the 1836 battle. The City Council didn’t care about the building’s historical significance; it was in the way and had to go.

In 1866, the city began demolishing the Galera, which was abruptly halted by the Catholic Church. The Church claimed that the building belonged to them, and the City had no right to tear it down. As the City and Church squabbled over who had ownership of the building, it sat in partial ruin, becoming a real eyesore. On March 7, 1869, on what was the 33rd, plus a day, anniversary of the Battle of the Alamo, the San Antonio Daily Express newspaper began a campaign, not to save the building where Jim Bowie had died, but to force its demolition.

Two years later, the City paid the Catholic Church $2,500 for the Galera, with the stipulation that they’d tear it down. Even though the “eyesore” Galera was gone, it didn’t stop the City from later granting a permit for another commercial building to be constructed on its site.

With the demolition of the Low Barracks, only two of the Alamo’s original buildings remained. But these, too, would continue to be degraded, with a total lack of their historical significance.

Honore Grenet (1823-1882)

After the U.S. Army vacated the Long Barracks, the Catholic Church received an offer of $20,000 for the purchase of the building from local merchant Honore Grenet.

Grenet had a grand idea of converting the building into a large, two-story shopping center. With the expansive Alamo Plaza at its front, everyone would be able to see his store unhindered.

As soon as the Church had accepted Grenet’s offer, he began ripping up what the Army had built, adding an outlandish design over what little was left of its Long Barracks’ original walls. Grenet’s idea was to capture the essence of the Alamo’s 1836 battle by making his store resemble a fort, complete with turrets and wooden cannons.

Although it was horrendous in what he did to the historic structure, these types of extravagant, over-the-top designs were very common for commercial buildings at that time. But again, it showed a total disregard by Grenet and the City in preserving what was left of the Alamo. But it gets worse!

Adding further insult to the Alamo, Grenet took out a lease on the Alamo’s church. This he used as a warehouse. Tourists coming to San Antonio to see the famous Alamo were allowed, for a fee, to tour the inside of the church. One visitor in 1882 complained of the smell of cabbage and Limburger cheese inside the historic building. And it just wasn’t cheese and vegetables that were kept in the church building; the carcasses of beef, pigs, and sheep were hung in the church’s cool, dark, limestone rooms. Some ill-informed visitors to the church thought that the blood stains on the floor and walls from the animals were those killed in battle.

When Grenet died in 1882, the shopping center/Long Barracks was sold to another mercantile company, Hugo and Schmeltzer. However, the new owner couldn’t use the Alamo church as a warehouse any longer; the Catholic Church had sold the building to the State of Texas three years earlier, also for $20,000, rescuing it from commercial hands.

A new era was about to begin for the Alamo’s church, but not its Long Barracks.

Restoring some dignity to the Alamo

With the State now owning the Alamo’s church, and with public pressure mounting to preserve what was left, the City of San Antonio began to feel patriotic, or at least somewhat historically responsible. They petitioned the State for custody of the Alamo church, which was granted.

The City didn’t have much funding, so any attempt to completely restore the church to its original look was out of the question. They were able to remove the second floor, but the other changes made by the U.S. Army were much too extensive.

Besides the two windows cut into the top of the church’s front (which I wrote about in Part III) the Army had also cut larger windows and doors throughout the rest of building. Removing those would have to wait.

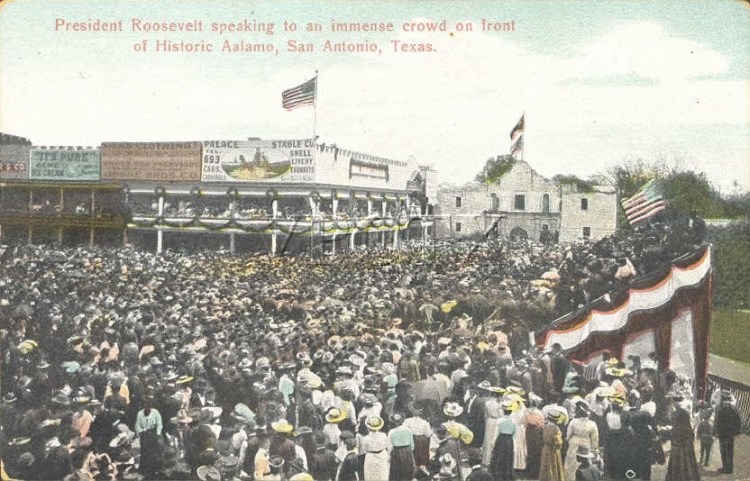

The City created the beginnings of a museum in the church, which was overseen by local historian Tom Rife. Rife gave tours to the ever-growing number of Alamo pilgrims. They came from all over the United States and the world to see where Travis had written his inspiring letter and where Davy Crockett had fought and died. However, they were greatly disappointed and even horrified at what they saw.

What they saw was the historic little church hemmed in by the overshadowing ghastly two-story mega-store on its left, and a row of saloons and small shops on its right, and there, sitting in the middle, was the Alamo, looking much like a roadside tourist trap.

On March 6, 1886, the 50th anniversary of the Alamo’s fall went largely unnoticed by those in charge of the Alamo. This caused outrage amongst the patriotic faithful. One of those was the San Antonio Express newspaper (the same paper that demanded the removal of the Low Barracks years before), which wrote an editorial demanding that a more historic and patriotic society be formed to save Texas history and the Alamo.

This cry was heard by two Angels, with a strong Texas history, who would first join forces to save the Alamo, but then battle against one another over their differing visions.

Some of the Sources Used:

Thompson , Frank. “From Army Headquarters to Department Store.” The Alamo: A Cultural History, Taylor Publishing, 2001.

Nelson, George. “The Alamo at the Time of Civil War.” The Alamo: An Illustrated History, third Revised Edition, Aldine Press, 2009, p. 95 and 98.

Lemon, Mark. “Lunette, Low Barracks.” The Illustrated Alamo 1836: A Photographic Journey, State House Press, 2008, pp. 22,24,28,30.

“Alamo Low Barracks and Main Gateway.” Texas Historical Markers on Waymarking.com, Waymarking.com, 2018, waymarking.com/waymarks/WM3DJ6_Alamo_Low_Barracks_Main_Gateway.

Wikipedia . “Alamo Mission in San Antonio.” Wikipedia , Wikipedia, 28 July 2018, en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alamo_Mission_in_San_Antonio.

“Honore Grenet.” Billion Graves, Billion Graves, billiongraves.com/grave/Honore-Grenet/12052402.

“Historic Photos of the Alamo.” Search: Historic Photos of the Alamo, Google, http://www.google.com/search?q=historic+photos+of+the+Alamo&rlz=1C9BKJA_enUS69:.

One thought on “The History of the Alamo, Part IV: From Warehouse to Roadside Attraction”