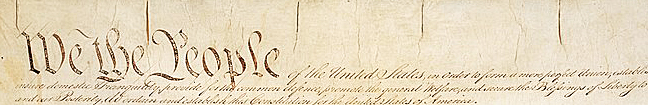

The Constitution of the United States of America is not just the governing foundation of our nation but the very essence of us as a people. However, most Americans think the U.S. Constitution usually refers to one or more of its first ten amendments. A while ago, I was talking to a friend about the political state of our country. He said, “We need to go back to the original constitution as it was written,” I said to him, “You mean before freedom of speech, religion, and the press, or the right to bear arms?” “Oh,” he answered, “that’s right, they’re amendments.”

The Constitution of the United States of America is not just the governing foundation of our nation but the very essence of us as a people. However, most Americans think the U.S. Constitution usually refers to one or more of its first ten amendments. A while ago, I was talking to a friend about the political state of our country. He said, “We need to go back to the original constitution as it was written,” I said to him, “You mean before freedom of speech, religion, and the press, or the right to bear arms?” “Oh,” he answered, “that’s right, they’re amendments.”

My original plan for these posts was to write about the history and background of the first ten amendments, using only the formation of the Constitution as background. But as I researched, I came to realize that I, too, only saw the Constitution through those amendments and was missing the amazing journey our founding fathers took in creating this nation of ours.

What were the needs and desires that took us from thirteen separate colonies and turned us into thirteen United States? What fears and concerns guided those framers to “form a more perfect union,” one that could adapt and grow with the better understanding that comes over time?

So, I begin before a nation was born, as we struggled to gain freedom during our Revisionary War.

The Articles of Confederation (1781-1789), the first constitution of the United States

As the Revolutionary War (1775-1783) intensified, the Continental Congress saw the urgency of forming a firmer union between the states to secure loans and other aid from foreign nations.

The first unification proposal was presented by Benjamin Franklin in July of 1775; this was never formally considered. A total of six proposals would be submitted and rejected. In June of 1776, Pennsylvanian John Dickinson’s proposed Articles were passed on to a committee for revisions. After a long deliberation, the entire Congress debated the revised Articles, which were approved and submitted to the thirteen states for ratification on November 15, 1777. On March

1, 1781 John Hanson, President of the Continental Congress, signed the Articles of Confederation into law, creating the new nation of the United States of America. Since Hanson was the President of the first governing congress of the new nation, technically, he would be the first President of the United States.

1, 1781 John Hanson, President of the Continental Congress, signed the Articles of Confederation into law, creating the new nation of the United States of America. Since Hanson was the President of the first governing congress of the new nation, technically, he would be the first President of the United States.

Article III of the Articles of Confederation described the relationship between the states as “a firm league of friendship… for their common defense, the security of their liberties, and their mutual and general welfare.” The biggest fear from the states was that a strong central government would take away states’ rights, but under these new Articles, the states remained sovereign. The new government would have one house of Congress with its members elected by the state’s legislation, the authority to form international alliances and treaties, make war, maintain an army and navy, coin money, establish a postal service, and manage Indian affairs. It couldn’t regulate foreign commerce or raise taxes; revenue would come from each state based on the value of its privately owned lands. Also, there would be no restrictions on trade between states, and each state would honor all judicial rulings of other states.

One major issue addressed in the Articles was Western expansion. Under original colonial charters, coastal states such as Maryland, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware, and Rhode Island were confined to a few hundred miles of the Atlantic coast. In contrast, other states’ charters allowed them to expand westward. Thomas Jefferson led the way with Virginia, which set limits to states expanding their border westward; this allowed the new lands to the west to become new states. This article set the guidelines for us to become our 50 States.

However, it soon became evident that giving the states so much authority was a major weakness of the Articles of Confederation. This, along with the inability to tax, forced Congress to take another look at the document.

The 1787 Constitution of the United States of America (1889-present)

With most of the powers of governance in the hands of the states, the Articles of Confederation gave the federal government very little authority. This led to much confusion, infighting, and the eventual strain on relationships between the “firm league of friendship” of the states. Also, foreign governments were still reluctant to deal with a United States that didn’t seem very united. To fix those issues, the Continental Congress called a constitutional convention to meet in Philadelphia in May of 1787 to revise the Articles.

Each state sent convention delegates, who were drawn from all sectors of society. These delegates were so knowledgeable and versed in issues of self-government that Thomas Jefferson referred to them as “an assembly of demigods.”

The delegates were instructed to only work on revising the exciting Articles, but as they discussed different revision options, they found it very difficult. After much debate, the delegation, led by the 36-year-old James Madison from Virginia, decided to scrap the entire Articles of Confederation for a completely new Constitution.

Those delegates with Madison were generally convinced that an effective central government with a wide range of powers was needed over the weaker Articles of Confederation. Madison, along with fellow Virginians Edmund Randolph and George Mason, presented to the delegation as a whole an outline for a new governmental constitution we now call “the Virginia Plan.” This document would become the bedrock for what would finally be the Constitution of the United States of America that we have today.

Those delegates with Madison were generally convinced that an effective central government with a wide range of powers was needed over the weaker Articles of Confederation. Madison, along with fellow Virginians Edmund Randolph and George Mason, presented to the delegation as a whole an outline for a new governmental constitution we now call “the Virginia Plan.” This document would become the bedrock for what would finally be the Constitution of the United States of America that we have today.

The convention’s delegates took almost a year to work out the new constitution. When finished, it consisted of only seven articles that would give the new federal government limited powers while protecting states’ rights. With the new constitution, articles I-III laid out the three branches of the government, with their authority and powers: the Legislative, Executive, and Judicial. Madison believed that this balance of powers would keep the republic from becoming a dictatorship.

Article IV addressed the relationship between the states. Jumping ahead, Article VI declared that this Constitution was the supreme law of the nation, and Article VII described the ratification process. Now, back to Article V. This article gave the guidelines for amending the Constitution; this article would be used even as the Constitution was undergoing ratification by the states.

However, many delegates, members of the Continental Congress, and state legislatures feared that a strong and decisive central government would infringe on states’ and individuals’ rights. They had just finished a long and terrible revolutionary war where a robust and powerful nation had taken away their basic rights as Englishmen. What the British had done to them during the war was crystal clear in their minds (I’ll be addressing those atrocities in my posts on the first ten amendments). They didn’t want to trade one oppressive government for another.

Soon, two groups formed: the Federalists, who supported a new, stronger central government, and the Anti-Federalists, who were opposed. James Madison, along with fellow Federalists Alexander Hamilton and John Jay, published what is known as the Federalist Papers, which defended the proposed constitution as being best for the country. They saw that their constitution still protected the states and individual citizens. The Anti-Federalists, with such revolutionary heroes as Patrick Henry, Samuel Adams, and Richard Henry Lee, didn’t see it that way and began demanding that a “Bill of Rights” be added. They feared that without a guarantee of individuals’ rights, the strong national government could suppress the people, leading to the president becoming a king.

At first, James Madison still believed that his “balance of power” concept would protect the people and that a Bill of Rights wasn’t needed. However, after Thomas Jefferson and George Washington wrote to him that some form of a bill of individual rights should be included and that some states would refuse ratification without it, Madison and his Federalists finally vowed to create and include a Bill of Rights.

As Madison and the other delegates began deliberating on adding individual rights to the Constitution, the Continental Congress decided to begin the state ratification process without them. But they promised the states that the new Congress, under the new Constitution, would make changes under Article V.

On September 13, 1788, in New York, the Continental Congress began transferring to the new Constitutional government with the required minimum of eleven state ratifications under Article VII. On March 4, 1889, the new government began operating under the new Constitution of the United States of America, and on April 30, George Washington was inaugurated as the first President under this Constitution.

As promised, the new Congress debated amending the Constitution with a Bill of Rights.

My upcoming posts

I’ll explore what could have been the reasoning, what resources were used, and what caused James Madison and the other framers to select those individual rights to protect in the first ten amendments. I’ll also give the history of how those amendments are viewed today.

Resources:

Wikipedia. “United States Constitution.” Wikipedia, 24 May 2018, en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Consitiution.

Researchers. “Primary Documents in American History.” The Articles of Confederation, Library of Congress, 25 Apr. 2017, http://www.loc.gov/rr/program/bib/ourdocs/articles.html.

“James Madison.” Bill of Rights Institute, Bill of Rights Institute, 2018, http://www.billofrightsinstitute.org.

“Bill of Rights Institute.” Bill of Rights, Bill of Rights Institute, 2018, http://www.billofrightsinstitute.org.