By the end of the 15th century, Spain had claimed for itself all of South and Central America and as far north in North America as California, Utah, Wyoming, Colorado, and Kansas. But claiming these lands and controlling them were two totally different matters.

The professional Spanish Conquistadors’ sole mission was to look for gold and silver, not to create settlements for Spain. This was very true with their North American claims. In fact, Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, and Kansas went completely unsettled by the Spanish. The Spanish also had problems in populating the extreme northern parts of Florida and Mexico.

Although British colonists from Georgia and the Carolina colonies had begun settling in northern Florida and its panhandle it was losing their state of Texas that worried Spain the most.

In 1689, near Matagorda Bay in Texas, they found the remains of French explorer La Salle’s Fort Saint Louis. Fearing French encroachment Spain needed some way to secure the northern lands of Mexico, and the best way was to establish settlements of their own. They chose a method that had been successful in other regions of Mexico and California, Catholic Church Missions.

The Mission system was created by the Franciscan order of the Catholic Church to spread Christianity among the native peoples. But it also provided permeant settlements that could attract other Spanish colonists to move near these missions.

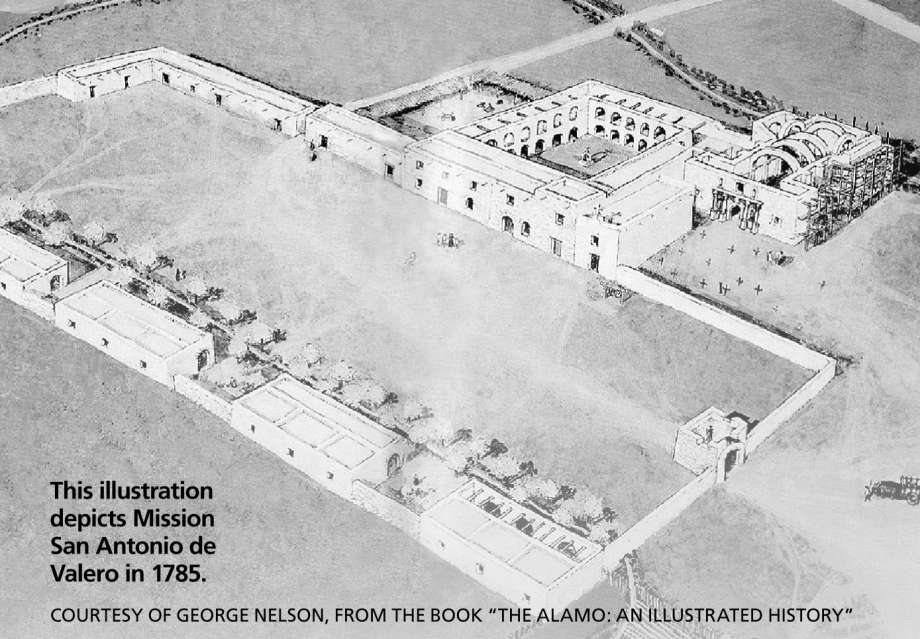

Of all the missions constructed in east Texas during this period, the largest concentration in North America were the five built along the San Antonio River. The first of these missions was San Antonio de Valero in 1718, followed by the missions San Jose, San Juan, Concepcion, and Espada. Each of these missions is roughly five miles apart, the distance a monk could walk in a day.

Today four of these five mission churches are still being used as active Catholic parishes. Only the first, San Antonio de Valero is not, but is by far the most famous.

In 1718, the San Antonio de Valero mission was founded near today’s San Pedro Springs Park in San Antonio. San Pedro Springs would be only the first of three sites for this mission. In 1724 it moved to its present location on the east side of the San Antonio River at an oxbow bend in that river.

In 1727 a two-story stone Convento, or priest’s residence, was completed, and in 1744 construction began on the mission’s first stone church. A small temporary adobe building was used for mass during its construction. This first church, with its bell tower and sacristy, collapsed in the 1750s due to poor workmanship.

Construction on the second, more ambitious, church began in 1758. Its limestone walls were four feet thick to support a barrel-vaulted roof, dome, and choir loft. Its design included twin bell towers and an elaborately carved façade. During this construction, the Indian population declined causing work to stop. This building would remain roofless and never finished, except for the carvings on the façade.

During this time the mission’s need for defense drastically changed due to a massacre of the missionaries and mission Indians at Santa Cruz de San Saba in 1758. Although Spanish soldiers had begun a defensive presidio (fort) across the river in San Antonio de Bexar it was never completed. Fearing for their safety the priests and mission Indians took it about themselves to fortify the mission by enclosing the complex with an eight-foot-high, two-foot thick wall and a fortified gate. Added to its defenses were a small number of cannons provided by the Spanish military.

For the next four decades, the mission San Antonio de Valero would house and support a small number of monks and declining Indian populations, while across the river the town of Bexar continued to grow.

By the late 1700’s the population of mission Indians had continued to decline throughout Texas, and also the hope that these missions would attract more Spanish settlers to northern Mexico hadn’t happened either. In 1793 Spain began to secularize, close down, the missions in Texas.

After secularization, the San Antonio de Valero mission’s grounds and buildings were given to the twelve remaining Indians still living within its walls, and the mission’s religious duties passed to Bexar’s San Fernando church across the river. Over the next decade, those twelve Indians would also move, leaving the mission compound to crumb in disrepair.

As the 19th century dawned Mexican Texas’ borders were again challenged by France. There was a disagreement over where the border actually was. Spain claimed it to be at the Red River, while France claimed it to be the Sabine River, 45 miles further west. The threat to their northern frontier became even more of a concern for Spain when the United States purchased Louisiana in 1803. There were already illegal French and American immigrants in Spanish Texas, and now the always expanding United States was at their very doorstep.

To help guard against further illegals from settling in Texas Spain increased its military presence throughout the region. They reinforced the small company of soldiers at San Antonio de Bexar with a Calvary company of one hundred men. These were the Second Flying Company of San Carlos De Alamo De Parras, named after the small town of San Jose y Santiago del Alamo, near Parras in the Mexican state of Coahuila.

Since a proper presidio hadn’t been built in Bexar the soldiers took up residency in the already walled Valero mission. Over time the mission Valero began to be called for the Calvary stationed there, and by 1807 military documents simply referred to the place as, the Alamo.

There is a legend that says that the mission’s name came from the rows of Cottonwood (Alamo is Spanish for Cottonwood) trees near it on the Alameda road. However, these trees were planted long after the mission was called the Alamo.

Reblogged this on History Present and commented:

Ron has produced an excellent history of the Alamo. From it’s construction to today, his posts cover the compound’s entire history. This is the first in a series of nine posts (so far?) on the subject. Just one of many series he has written on various subjects.

LikeLike

Thank you for reposting and the kind words

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on quirkywritingcorner.

LikeLike

It’s interesting to me that you pointed out that so many missions had performed defense functions to promote new settlements in the west. The Alamo it seemed got more attention that it deserved.

LikeLike

What made the Alamo different was the 13 day siege and final pre-dawn battle. Also the Alamo’s defenders mythical “last stand” against overwhelming odds raised that battle to legendary status. So powerful was the legend of the Alamo that it changed the course of Texas and U.S. history.

LikeLike